We are so often a disappointment to the parents who abandon us.

A male voice interrupted my thoughts, speaking the language of Carthage. 'Papers, freeman--'

The man broke off as I turned to face him, as people sporadically do.

For a moment he stood staring at me in the flaring naphtha lights of the harbour hall.

'--freewoman?' he speculated.

People shoved past us, shouting at other harbour guards; keen to be free of the docks and away into the city of Carthage beyond. I had yet to become accustomed to the hissing chemical lights in this red and ivory stone hall, bright at what would be midday anywhere else but here. I blinked at the guard.

'Your documents, freeman,' he finished, more definitely.

The clothes decided him, I thought. Doublet and hose make the man.

The guard himself-one of many customs officers-wore a belted robe of undyed wool. It clung to him in a way that I could have used in painting, to show a lean, muscular body beneath. He gave me a smile that was at least embarrassed. His teeth were white, and he had all of them still. I thought him not more than twenty-five: a year or so older than I.

If I could get into Carthage without showing documents of passage, I would not give my true name. But having chosen to come here, I have no further choice about that.

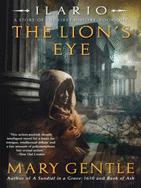

The Carthaginian customs officer examined the grubby, wax-sealed document that I reluctantly handed over. '"Painter", Freeman...Ilario?'

King Rodrigo Sanguerra had not been angry enough to refuse me travelling papers, now he had freed me, but he left me to fill in my own profession-furious that I would not consent to the one he wanted. But I am done with being the King's Freak. Nor will I be the King's engineer for machines of war.

'My name is Ilario, yes. Painter. Statues; funeral portraits,' I said, and added, 'by the encaustic technique.'

Show me a statue and I'll give the skin the colour of life, the stone draperies the shadows and highlights of bright silks; ask me for a funeral portrait, and I'll paint you a formal icon with every distinguishing symbol of grief. I thought it likely that people in Carthage would want their statues coloured and their bereavements commemorated, as they do elsewhere.

'It's a good trade.' The man nodded absently, running his wide thumb over the seal of King Rodrigo of Taraconensis. 'We get a lot of you people over from Iberia. Not surprising. You shouldn't have any trouble getting Carthaginian citizenship--'

'I'm not here to apply for citizenship.'

He stared at me as if I had taken a live mouse out of my mouth. 'But you're immigrating.'

'I'm not immigrating.'

The Visigoth Lords of Carthage tend to assume that every man and woman would be one of them if they could. Evidently the assumption extends to their bureaucracy.

'I'm visiting here. On my way to Rome,' I said, using the Iberian term for that city that the Europeans call 'the Empty Chair', since St Peter's Seat has stood unoccupied these many generations. 'There are new things happening--'

They are putting aside painting the iconic meaning of a thing, and merely painting the thing itself : a face, or a piece of countryside, a sit would appear to any man's naked eye. Which is appalling, shameful, fascinating.

'--and I intend to apprentice myself under a master painter there. I've come here, first'...I pointed...'to paint that.'

This hall is the sole available route between the Foreigners' Dock and Carthage itself. Through the great arched doorway in front of me, the black city stood stark under a black sky, streets outlined by naphtha lamps. Stars blazed in the lower parts of the heavens, as clearly as I have ever seen them above the infertile hills behind Taraco city.

Stars should not be visible at noon!

In the high arch of the sky, there hung that great wing of copper-shadowed blackness that men call the Penitence-and where there should have been the sun, I could see only darkness.

I glanced back towards the Maltese ship from which I'd disembarked. Beyond it and the harbour, on the horizon, the last edge of the sun's light feathered the sea. Green, gold, ochre, and a shimmering unnatural blue that made me itch to blend ultramarine and glair, or gum arabic, and try to reproduce it...

And yet it is midday.

Even when the ship first encountered a deeper colour in the waves, I had not truly believed we'd come to the edge of the Darkness that has shrouded Carthage and the African coast around it for time out of mind. Did not believe, shivering in fear and wonder, that no man has seen sunlight on this land in centuries. But it is so.

It alters everything. The unseasonal constellations above; the naphtha light on ships' furled sails at the quayside; the tincture of men's skin. If I had my bronze palette box heated, now, and the colours melted-how I could paint!

'You're a painter.' The man stared, bemused. '...And you've come here where it's dark .'

A sudden clear smile lit up his face.

'Have you got a place to stay? I'm Marcomir. My mother runs a rooming-house. She's cheap!'

My mother is a noblewoman of Taraconensis.

And she will attempt to kill me again, if she ever finds me.

Marcomir looked down at me (by a couple of inches), slightly satisfied with himself. I thought there was a puzzled frown not far behind his smile. This short, slight man -he is thinking- this man Ilario, with the soft black hair past his shoulders; is he a woman in disguise, or a man of a particular kind?

The latter will be more welcome to this Marcomir, I realised.

The brilliance of his dark eyes would be difficult but not impossible to capture in pigments. And the city of Taraco, while only across the tideless sea, beyond the Balearic Islands, seems very far away.

'Yes,' I said, automatically using the deeper tones in my voice.

There'll be trouble, accepting such an invitation, since I'm not what he thinks I am, but that kind of trouble is inevitable with me.

I shouldered my baggage and followed him away from the harbour, into narrow streets between tall and completely windowless houses. And steep! The road was cut into steps, more often than not; we climbed high above the harbour; and it had me-I, who have hunted the high hills inland of Taraco, and habitually joust in day-long tourneys-breathing hard.

'Here.' Marcomir pointed.

I halted outside a heavy iron door set into a granite wall. 'You do know I'm...not like most men?'

Marcomir's eyes gleamed bright as his smile when he flashed them at me. 'Was sure of that, soon as I looked at you. You got that look. Wiry. Tough guy. But...elegant, you know?'