Thank you for purchasing this Free Press eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Free Press and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this Free Press eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Free Press and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

THE FREE PRESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com.

Text and illustrations copyright 2001 by Great Projects Film Co.

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

THE FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks

of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Elton Robinson

ISBN-13: 978-0-74321-476-6 (eBook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

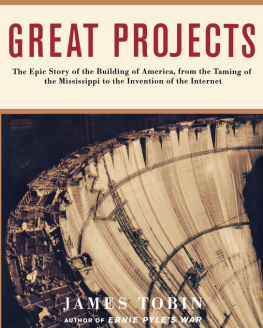

Tobin. James. 1956

Great projects: the epic story of the building of America, from the taming

of the Mississippi to the invention of the Internet / James Tobin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. EngineeringUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

TA23 .T63 2001

609.73dc21

2001033016

ISBN: 978-1-4516-1301-8

CONTENTS

A nyone who has watched Frank Capras Its a Wonderful Life has heard a classic expression of the American urge that lies at the heart of this book. It comes on the night when George Bailey (James Stewart) and Mary Hatch (Donna Reed) are falling in love. Following the town tradition, George makes a silent wish as he pitches a rock at the broken-down house that Mary and he soon will make their own. Whatd you wish, George? Mary asks, and he tells her: Well, not just one wish. A whole hatful, Mary. I know what Im going to do tomorrow and the next day and the next year and the year after that.... Im going to build things. Im gonna build air fields. Im gonna build skyscrapers a hundred stories high. Im gonna build skyscrapers a hundred stories high. Im gonna build bridges a mile long.

The American experience usually is defined by reference to abstract nounsdemocracy, individualism, freedom. But one concrete verb is at least as fittingto build. That is what Americans do; George Bailey felt it in his bones. It may be unfashionable now to speak of a single, distinctive American character. But one cannot review the centuries since the American revolution without concluding that building, fashioning, on scales both small and epic, have been central to the nations experience. Nor can one escape a sense of awe at the structures Americans have raised on the continent they claimed as their own by virtue of what they built on it. It also may be unfashionable to acknowledge the debt that Americans owe to the engineers and builders of earlier generations. Yet the civilization we take for granted would be impossible without their handiwork. The drive to put stone upon stone, creating on earth the city upon a hill the Puritans imagined, suffuses American history. America is never accomplished, the poet Archibald MacLeish wrote. America is always still to build. MacLeish meant this as a metaphor, but it was also a literal fact.

Yet historians have given short shrift to those who conceived and carried out the actual building. Just as victors tell the history of war, writers tell the history of nations. This has left engineers at a disadvantage. They tend to do their best thinking in images, not in words. They obey rules of physics the rest of us understand dimly, if at all. They work in the realm of numbers, and they believe their creations speak for themselves. Not many have written their own stories. At one point in his career, Frank Crowe, the chief engineer of Hoover Dam, was asked to write an autobiographical sketch of one thousand words. He turned in forty. Thomas Edison was called the Wizard of Menlo Park because most of his countrymen found his pioneering work in electrical engineering to be as incomprehensible as magic. How many of ushistorians includedtruly comprehend Edisons work a century later? Americans have admired their engineers from afar. But few have learned much about them.

This book is a step toward fuller appreciation of the role engineers have played in American history. It offers a history of engineering through the stories of eight great enterprises that have shaped American landscapes and expressed American dreams. The stories are grouped in four parts, each corresponding to an essential task of the engineerto protect people from the destructive force of water while harnessing water for the enormous good it can do; to provide people with electricity, the motive force of modern life; to make great cities habitable and vital; and to create the pathways that connect place to place and person to person.

But these stories are not principally about the technical intricacies of structures and machines. They are about people, chiefly the engineers themselvestheir ambitions, their battles, their genius. The stories are also about planning and politics, the processes without which great engineering projects would remain only blueprints. Not one of these projects was realized simply because an engineer had a brilliant vision, or because the project was technically feasible, or because it would benefit the public. Each had to be pushed through the sticky medium of public controversy and debate. The American tradition of public works grew up in the public arena as much as on the construction site. Indeed, the battles in the public arena were just as difficult as the work of design and construction, and they demanded at least as much persistence and courage.

The eminent American historian Daniel Boorstin once wrote that although democracy was usually described in terms of self-government, I prefer to describe a democratic society as one which is governed by a spirit of equality and dominated by the desire to equalize, to give everything to everybody. In the United States, Boorstin said, technology has served to democratize our daily life. The projects described here surely have expressed and accelerated that tendency. Enterprises undertaken for the sake of safetythe Mississippi levees, the Croton Aqueductwere built for the safety of all, not only of a monied elite. Projects that aimed to enhance the quality of lifeelectrification, the Big Dig, the Internetembraced more and more people as they grew. They provided tools for what the founders called the pursuit of happiness.

As everyone knows who has watched Its a Wonderful Life, George Bailey never gets to build his bridges. Like most of us, he must stay at home, tending to the business of family and town. Only a few have been privileged to stand deep in Black Canyon with Frank Crowe, imagining a dam, or at the edge of the Hudson River with Othmar Ammann, imagining a bridge. But the structures they built remain, and the structures have stories to tell.

Next page