Contents

About the Book

For I know, that, although during my life some have despised me, yet after my death you will see what sort of man I was, and that my doctrine was by no means worthy of contempt. From Bedes Life of St Cuthbert

Life and death. Glory and contempt. Doctrine and devotion. Anglo-Saxon saints have navigated their way across many centuries, down to our modern world, preserved on street corners, national flags and village halls. While remembered as little more than a name in many cases, the saints of the first millennium were the movers and shakers, the decision makers of the time.

About the Author

Dr Janina Ramirez is an Oxford lecturer, BBC broadcaster, researcher and author. Janina is the course director for the Undergraduate Certificate and Diploma in History of Art at the University of Oxford. She presents her ideas widely at conferences, public speaking and outreach events, and publishes her research in journals and magazines. She has presented and written over six BBC history documentaries and series, is a regular guest on the new BBC series Quizeum and is currently working on a number of projects including a three-part series for Radio 4. She lives in Oxfordshire with her young family.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9780753550656

Version 1.0

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

WH Allen, an imprint of Ebury Publishing,

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

WH Allen is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright Dr Janina Ramirez 2015

Dr Janina Ramirez has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published by WH Allen in 2015

www.eburypublishing.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780753555606

This work is dedicated to Dan, Kuba, Kama, Babi, Papa, and all those who love and inspire me. Aere Perennius.

All it takes to make a man a saint is grace. Anyone who doubts this knows neither what makes a saint nor a man.

Blaise Pascal, Penses, VII, 508

Introduction

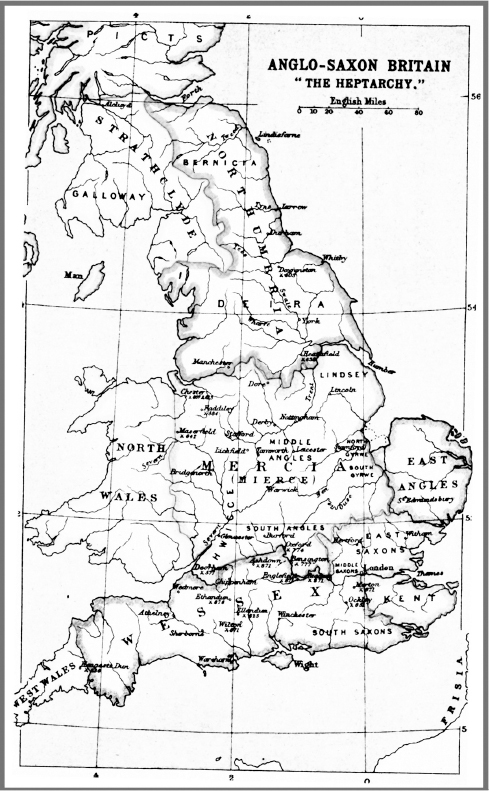

Saints names echo through the centuries. Today we may walk down St Gregory Street, past St Bedes Primary School, or find a church dedicated to St Cuthbert. The saints are in our peripheral vision, part of the subtext of the nation, but the actual people behind the names are shrouded in the mists of time. Inhabitants of a dark age, figures like Alfred the Great, Edward the Confessor or Bede the Venerable straddle the part of our collective memories that dissolves legend with historical fact, myth with real people. But the saints can provide a pin upon which to hang other evidence of a lost past. They are fascinating in their diversity, and can reveal a great deal about the times in which they lived and died. It is now their time for reassessment; time to reveal their private lives.

Growing up in a Polish/Irish Catholic household, I am well acquainted with the saints. Images of the traditional early saints, like Christopher, Catherine and Peter, jostled for supremacy next to Padre Pio and Pope John Paul II. Comforting faces peering out from frames, they provided the young me with a sense that an army of righteous, sacred souls were guiding me through life. These early interactions with the saints left a lasting impression. Although I now approach them as historical figures, rather than the focus of devotion, this experience allowed me to reconcile my own probing academic view on medieval saints with a more fundamental understanding of the spiritual potency these individuals can command.

However, my recent renewed fascination with the saints, and the Anglo-Saxon ones in particular, began while reading a tabloid newspaper. I have been passionate about the Anglo-Saxon period from the first moment I encountered the Old English Elegies as an undergraduate student. One passage from The Wanderer in particular seemed to resonate down the centuries:

| Her bi feoh lne, | Here money is fleeting, |

| her bi freond lne, | here friend is fleeting, |

| her bi mon lne, | here man is fleeting, |

| her bi mg lne, | here kinsman is fleeting, |

| eal is eoran gesteal | all the foundation of this world |

| idel weore! | turns to waste! |

| The Wanderer. |

Old English texts like this offer timeless insights into the human condition, and yet they grew from the minds and imaginations of people with their own distinct views, attitudes, concerns and symbolic frameworks. Its the world of Beowulf, of mystical smiths crafting unimaginably beautiful jewellery, of wandering monks in the wilderness, of the clash and howl of hand-to-hand combat. It was a world that, to me, seemed both within my reach and at the same time impossible to grasp fully, as to understand it I had to learn more about the people themselves and the landscapes (both intellectual and real) that they inhabited.

However, as I flicked through newspaper pages, past models, actors, politicians and celebrities, I began to wonder what an Anglo-Saxon version of such a publication would look like. Whose faces would be staring out at me? Whose lives would readers be following? Who would be the pin-ups and heroes of the Anglo-Saxon period? Traditionally, we might think it would be kings, queens, nobles and warriors. But we are overlooking a far more prevalent and influential body of individuals, whose importance resonated across the social spectrum the saints. Representatives of a powerful, all-pervading Church, their designation as extra-special Christians ensured their celebrity and reputation. It is their stories that have been passed down the centuries, and their names that are repeatedly tied to specific places and events.

To uncover the lives of Anglo-Saxon saints is to open a window onto a fascinating and rich period in our nations history. Archaeological discoveries over the past century have rendered the term Dark Ages redundant. Far from nasty, brutish and short, life in the Anglo-Saxon period could be vibrant and exciting. Anglo-Saxons didnt simply live in wooden huts, but in grand palace and monastic complexes like those at Yeavering and Winchester. They werent primitive, uncivilised people, but were instead capable of technical wizardry that could produce stunning objects like the Sutton Hoo shoulder clasps and the Lindisfarne Gospels.