Pagebreaks of the print version

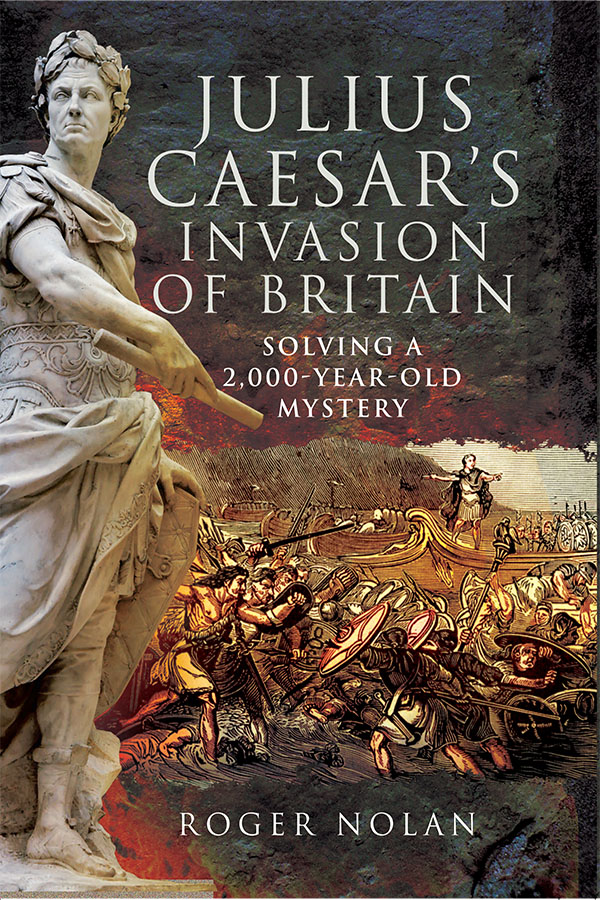

JULIUS CAESARS INVASION OF BRITAIN

SOLVING A 2,000-YEAR-OLD MYSTERY

For Joseph and Charles

JULIUS CAESARS INVASION OF BRITAIN

SOLVING A 2,000-YEAR-OLD MYSTERY

ROGER NOLAN

Julius Caesar's Invasion of Britain

Solving a 2,000-Year-Old Mystery

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd, Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Roger Nolan

ISBN: 978-1-52674-791-4

eISBN: 978-1-52674-792-1

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-52674-793-8

The right of Roger Nolan to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted

by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP

catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in

writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology,

Air World Books, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History,

Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore

Press, Frontline Books, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and White Owl

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, UK.

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS,

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Acknowledgements

M y initial thanks go to Peter Salway whose footnote in his excellent book Roman Britain was the catalyst which started me on the investigation which resulted in the discovery of the marching camps established by Julius Caesars army.

Although this book has by and large been a one-man exercise, I have had help from a number of people and organisations during the long period of research and investigation.

In the early days of my researches, I had much help from the staff at the museum at Canterbury.

In particular, I owe a debt of gratitude to Jak Showell for his kind advice and wise counsel based on his vast experience of authorship and the means of bringing a book to publication as well as his encouragement during the writing of this book.

Many thanks to Kevin Diver of Thurrock Council for opening the Coalhouse Fort at East Tilbury to enable me to photograph the Thames crossing from the ramparts of the fort.

My grateful thanks are due to John Grehan at Frontline Books for guiding me through the complicated process of commissioning this book.

Finally, very special thanks to Sally Robinson who first suggested I set down in writing the results of my researches over the years and supported me and encouraged me throughout the process of writing this book.

Roger Nolan,

Littlestone-on-Sea,

2018.

Foreword

T he great fascination of the early history of the British Isles is not what we know, but what we dont know, for this opens up the opportunity for discovery. Such discoveries add to our growing knowledge and understanding of the past, though some sow confusion when they appear to counter previously-accepted theories. This is no more so than with the invasions of Julius Caesar in the first century BC. With seemingly little archaeological evidence to guide us, the landing places and routes through southern England taken by Caesars army have been determined more through calculated interpretation than hard facts. That was until the uncovering in 2017 of a massive Roman encampment at Pegwell Bay on the Isle of Thanet.

As is often the case, this discovery was made during archaeological excavations before a new construction programme, in this instance, the building of the new East Kent Access road. The site, which may be up to twenty hectares in size, includes a defensive ditch some four to five metres deep and two metres wide, has yielded finds that have been identified as first century BC, including a Roman pilum (javelin). It has been said by archaeologists from the University of Leicester headed by Dr Andrew Fitzpatrick, that the shape of the ditch at Pegwell Bay is very similar to some of the Roman defences at Alsia in France, where a decisive battle in the Gallic Wars took place in 52 BC.

There is, therefore, a high probability that this is one, and arguably the most important, of Caesars camps. As has been stated by the spokesperson for the University of Leicester dig, the Isle of Thanet had not previously been considered a likely landing place because it was separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Channel and this still presents us with a problem reconciling Pegwell Bay with Julius Caesars own detailed account of his invasion of Britain.

Looking at Caesars first invasion in 55 BC, we read that he advanced about seven miles and stationed his fleet over against an open and level shore. But the barbarians, upon perceiving the design of the Romans, sent forward their cavalry and charioteers, a class of warriors of whom it is their practice to make great use in their battles, and following with the rest of their forces, endeavoured to prevent our men landing. The question must be asked, how did the Britons move along the coast and then transport their horses and chariots across the Wantsum Channel in time to oppose Caesars soldiers before they had waded ashore. Movement along land, following simple tracks, was notoriously slow compared with sea travel, which is why, as Caesar states, the Britons sent forward their cavalry and charioteers as these were the only ones that could keep pace with the Roman fleet.

The Britons could not have known where Caesar would make landfall, which is why they followed the invasion fleet. When it was seen that the Romans were going to attempt a landing on the Isle of Thanet, they would, somehow, have had to manhandle their chariots, along with what must have been a considerable number of horses, onto boats to cross the Wantsum Channel in time to be ahead of the Romans if indeed they had a large number of suitably large vessels waiting for them to jump into. None of this could have happened.

Furthermore, there would have been no advantage to the Romans in landing on the Isle of Thanet, as they still had water to cross to reach the mainland. Some indication of the degree of obstacle the Wantsum Channel represented can be gleaned from the investigations of the Kent Archaeological Society paper presented by F. W. Hardman and W. P. D. Stebbing: We conceive it as a natural arc-shaped stream of tidal water cutting off Thanet from the mainland with a breadth of about two miles and a depth of about forty feet and with wide open ends. It formed a safe roadstead for ships and a sheltered line of communication with the Thames.

Equally, one would imagine, that the British would have waited on the mainland for the invaders to cross the Wantsum Channel before attacking, as this would have given them more time to bring up their foot warriors.

Lastly, as Roger Nolan has found, none of this ties in with Caesars account, which is in other regards, quite specific in its details.