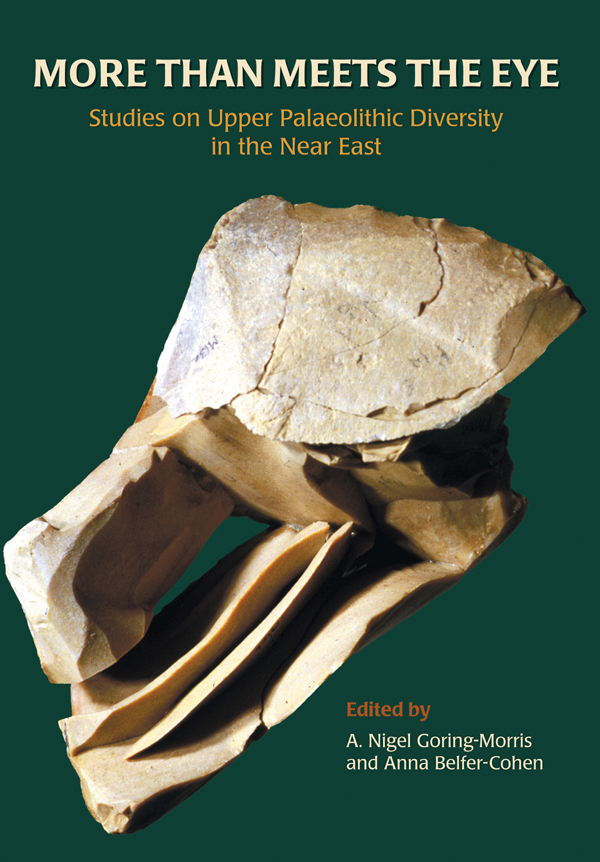

More Than Meets The Eye

Studies on Upper Palaeolithic Diversity in the Near East

Edited by

A. Nigel Goring-Morris and Anna Belfer-Cohen

Oxbow Books

First published in the United Kingdom in 2003. Reprinted in paperback in 2017 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and the individual contributors, 2003

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-914-2

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-915-9 (epub)

Mobi Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-916-6 (mobi)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

| UNITED KINGDOM | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA |

| Oxbow Books | Oxbow Books |

| Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449 | Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146 |

| Email: | Email: |

| www.oxbowbooks.com | www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

Front cover: Refitted core from Nahal Nizzana XIII (photo: Z. Radovan)

Back cover: left, Advat area with Boker Tachtit and Boqer; right, Ohalo II (photo courtesy of D. Nadel)

Foreword

Reading More than Meets the Eye: Studies on Upper Palaeolithic Diversity in the Near East Or Why You Should

The volume before you is an important one. It is clearly important for specialists working on Near East Pleistocene lifeways because it brings together most of the key players and has them direct their attention to a specific topic- the diversity in the archaeological record between some 50 and 10,000 years ago. For me the books importance, however, lies beyond a state of the art synthesis of a regional record at a specific point in time. This is because the volume addresses a seminal issue relevant to all scholars interested in understanding the past namely, the significance of the observed diversity in the record.

The contributors to this volume amply document great variability in the archaeological remains recovered at one point in time from an area of some 140,000 km of the occupied Upper Palaeolithic oecumene. Such synchronic variability in what was less than 1.0% of the total landmass occupied by our ancestors warns us to expect similar synchronic diversity in all of the areas outside of the Near East as well. And this is, in fact, precisely what is being observed more and more from other well studied areas such as France, Moravia, and Russia in both its European and Siberian parts.

Various chapters in this volume also document variability through time. While our chrono-cultural schemes which see Middle Palaeolithic industries replaced by Upper or Late Palaeolithic ones certainly lead us to expect such change through time, a number of the authors in the ensuing pages also argue for synchronic diversity in archaeological remains recovered from sites dating to the transition from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic and thus point to different pathways likely taken to modern human lifeways ostensibly achieved some 40,000 years ago.

The documentation of variability in the archaeological record necessarily raises the question about its meaning and significance. Synchronic and diachronic diversity clearly reflects many factors. First, variability increases with an increase in the volume of the record on hand. The more sites we know in a region, the longer research has been conducted there, or the more scholars who have worked with that record the greater the changes to see diversity. The direct positive relationship between abundance and diversity is a well known statistical phenomenon, one highlighted for prehistoric archaeologists by scholars working on various measures of diversity (see discussion in Kerry and Henry, this volume). Given this, it is less than surprising then to find in the history of prehistory that while our l9th and early 20th century predecessors stressed mean/modal tendencies, those of us working a century later problematize variability.

It is also true, as some contributors to this volume point out, that greater variability is perceived when scholars from different research traditions work with analogous data. The Near Eastern research record is a veritable Tower of Babel in this respect, with knowledge and insights having been generated by scholars hailing from Great Britain, France, Israel, the United States, and Japan. Next, as Belfer-Cohen and Goring-Morris point out in their introductory chapter, in archaeology as in paleoanthropology personal paradigmatic preferences are also at play with some scholars highlighting central tendencies and thus leaning towards lumping while others place greater value on differences and privilege splitting.

When we combine these factors with the inescapable reality that in archaeology, especially in lithic studies, the vast majority of variables we work with are not discrete but continuous, little wonder than that our end products wind up as polyphonic interpretations.

Acknowledging all this necessarily puts us before the first crucial question: namely, is the observed variability be it through time or across space just a product of our and our predecessors research contexts? I believe that the volume before you convincingly demonstrates that no, the diversity they observe is not only of our own making something created by researchers themselves. Rather, some and just how much remains to be established came about through the diverse actions of people who lived in the Near East during the late Pleistocene.

Having demonstrated this, many of the contributors to More Than Meets The Eye: Studies on Upper Palaeolithic Diversity in the Near East then proceed to examine a variety of potential generators of this variability. All the usual suspects are considered from climate and culture and the different capacities all the way to possible differences in social organization, in styles of teaching and learning, and finally in ways of being in the world. The strength of this volume lies precisely in the variety of options considered and in the fact that while different authors may favor one explanation over another for the record at a particular point in time, at other times or in other places they champion different explanations as being more satisfactory. This inexorably underscores the importance of contingency or history something rarely considered in Palaeolithic archaeology.

Another major issue considered in this book that I find significant beyond the confines of the Palaeolithic Near East is the question of what spatial scale to select as our unit of study. A number of contributors find our traditional focus on a single site satisfactory, yet for others often asking different questions a single site is insufficient. Although the way we choose to organize our research today as well as our research traditions do favor a single site such an analytic unit is clearly too small when problematizing diversity and its significance or lack thereof.

I am also happy to see that this volume indirectly raises one of my favorite questions: was Palaeolithic life lived by stone alone? If not, as clearly was the case - then why do we still continue our lithocentric focus when working on prehistory? Some authors invoke preservation biases that inevitably come in once we try to operationalize such awareness. While admittedly organics do, indeed, not preserve at some sites, should this absolve us from the need and the duty to not only study such more perishable remains as diligently and exhaustively as we do the lithics, but also to routinely employ recovery techniques designed to optimize our chances of recovering them? The most glaring example of our failure to do so, as Phillips and Saca note, is the fact that while water screening is used at most, if not all, Palaeolithic excavations flotation is most assuredly not. The two are not equivalent the first can and does destroy such perishables as charred plant materials. Given such destructive recovery methods little wonder then that we fail to routinely recover vegetal remains from Palaeolithic contexts.

Next page