Contents

To the North Korean people I know and to

those I have never met. I will never forget you.

First published in 2021 by September Publishing

Copyright Lindsey Miller 2021

The right of Lindsey Miller to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted

by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

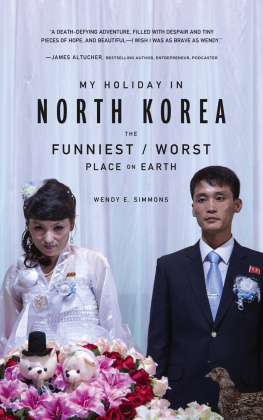

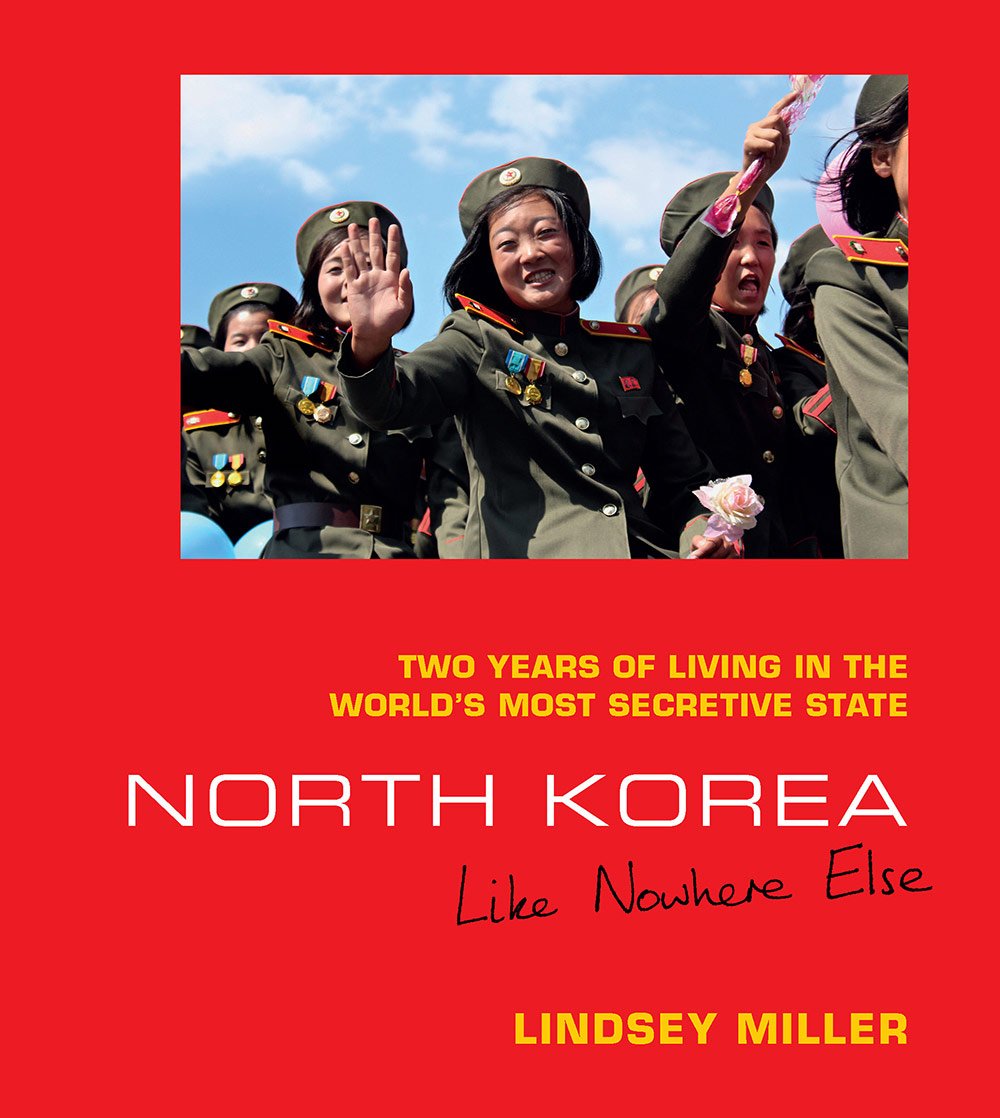

cover images:

(

) 70th anniversary of the founding of the country parade. Pyongyang, September 2018

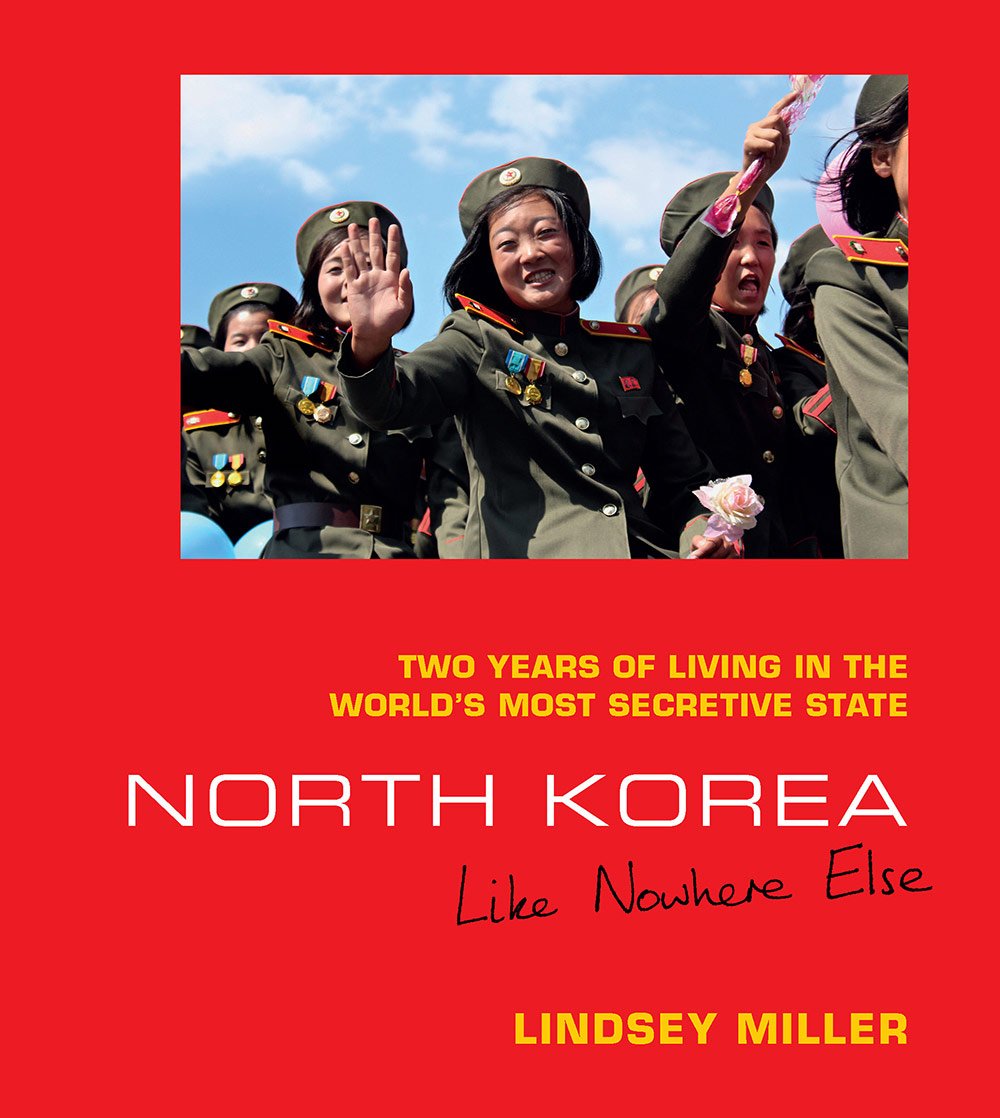

(

) Upstairs and downstairs. Pyongyang, September 2018

endpaper images:

(

) The 2018 Mass Games. Pyongyang, October 2018

(

) The 2019 Mass Games. Pyongyang, August 2019

Design and sequence by Friederike Huber

Printed in Poland on paper from responsibly managed, sustainable sources

by Hussar Books

ISBN 9781912836529

September Publishing

www.septemberpublishing.org

TWO YEARS OF LIVING IN THE

WORLDS MOST SECRETIVE STATE

NORTH KOREA

LINDSEY MILLER

We must envelop our environment

in a dense fog, to prevent our enemies

from learning anything about us.

Kim Jong Il

(

)

A wooden bridge leads to a pier. Wonsan, October 2018

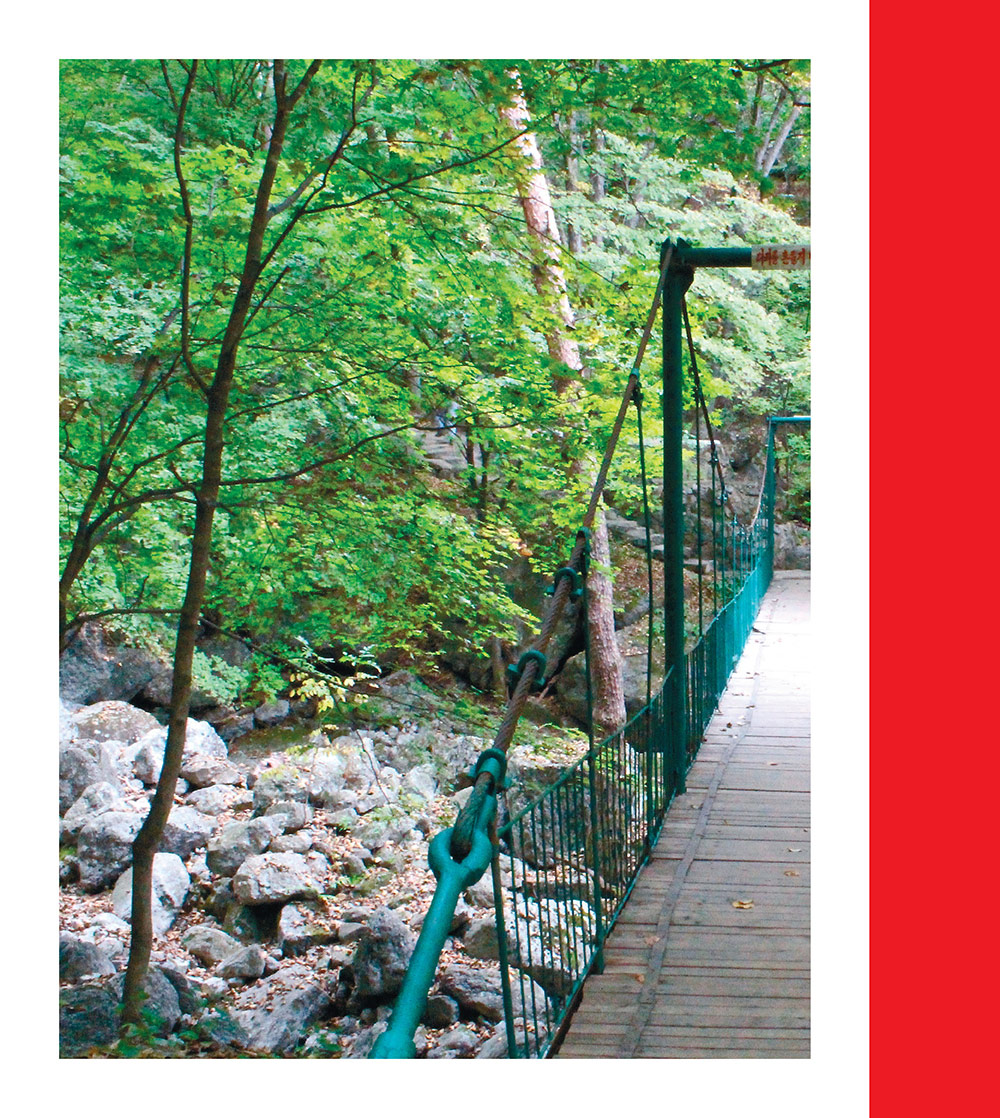

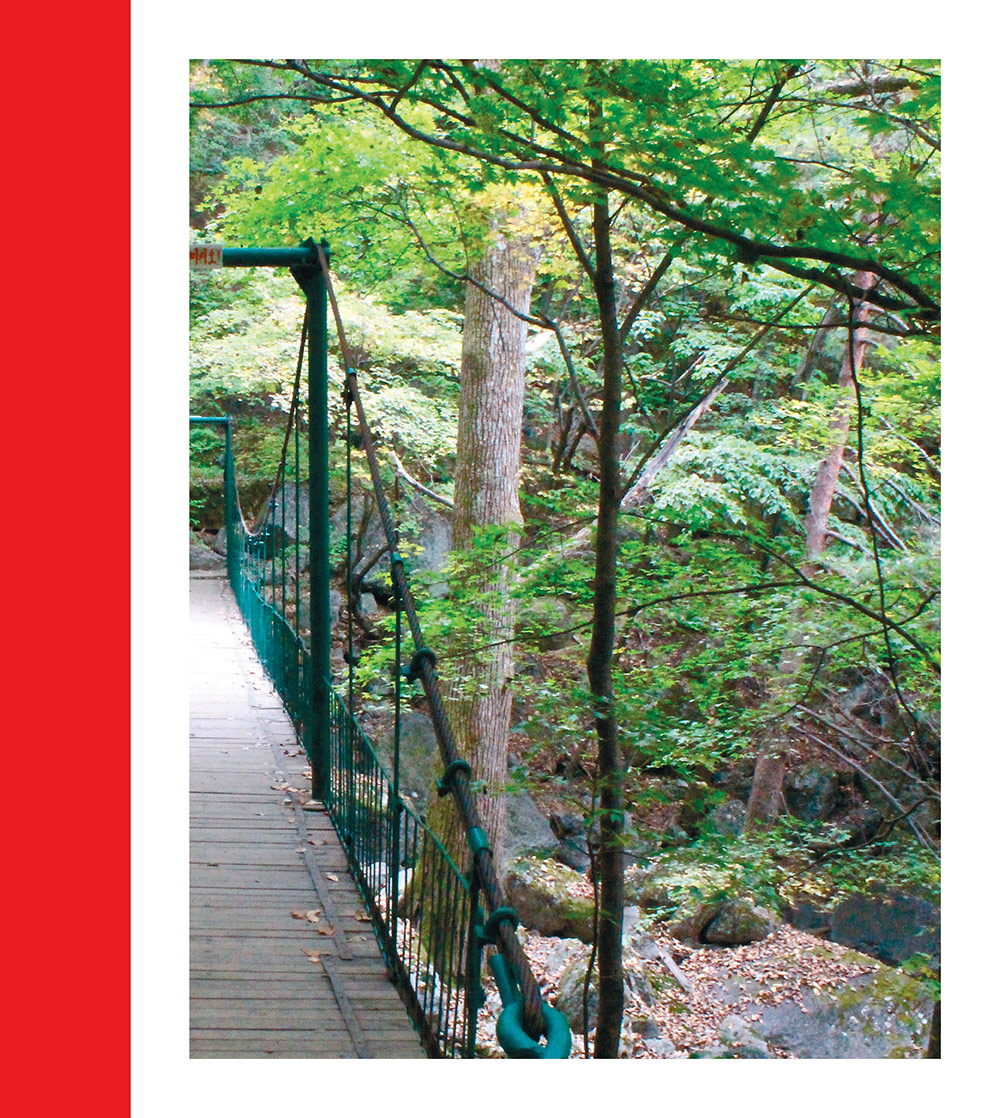

A bridge takes hikers over a trickling stream. Mount Myohyang, October 2018

The Chungsong Bridge. Pyongyang, August 2019

INTRODUCTION

How much can you really know a place?

Many of us try to learn about foreign countries and people by trusting

what we see in front of us. We learn from our experiences, what we can sense,

what we feel: our most basic instincts. We also consider the opinions of others,

using them to inform our own. From something unknown we feel like we start

to understand.

But what happens when you go somewhere where even basic truths are

ambiguous; where sometimes you cant trust your own eyes or even what you

feel; where the divide between real and imagined is never clear? Are some

places simply condemned to be beyond our understanding?

I found myself tormented by these questions for two years when I moved

to North Korea in 2017 to accompany my husband on a diplomatic posting to

the British Embassy in Pyongyang. Before I arrived I knew that North Korea was

a place where foreigners were routinely arrested for relatively minor crimes,

occasionally with dire consequences. I knew that a pervasive cult of personality

subsisted on air-lifted lobster and caviar, while most of the population was

condemned to beggary and misery. Depending on who I asked, there were

100,000 to 250,000 people languishing in prison camps. And, yes, Id seen

the footage of goose-stepping soldiers, Cold War-style military parades, ballistic

missile and nuclear tests, and the almost comedic, profound yet ultimately

inconsequential, otherworldliness of the place. But I had no idea what to expect,

and no sense of how North Korea would change my life forever. Moving to

North Korea turned out to be the biggest leap Id ever taken. If I live for a

hundred years, its unlikely anything will surpass it.

Four months after I had decided to go, I stepped into North Koreas hot and

muggy summer air for the first time. I stood at the top of the small and rickety

airplane stairs and breathed in my surroundings, accented with the smell of

pine trees, plane fuel and the cigarette smoke emanating from the cockpit. As

I took in the desolate concrete runway and listened to several soldiers berating

the baggage handlers for something I couldnt understand, I had no idea that,

over the next two years, what Id always considered to be the clear line between

truth and fiction would disintegrate entirely.

We lived in a compound in eastern Pyongyangs Munsu Dong district,

where most of Pyongyangs tiny foreign community lived and worked. Within the

larger Munsu Dong international compound, smaller compounds housed the

accommodation blocks, embassies and offices that lined several streets. There

were a couple of hard-currency shops, a handful of bars and a school attended

by the children of foreign residents. We lived in the old German Democratic

Republic compound, home to a mini-community of German, British, French and

Swedish diplomats. The streets of the international compound were overlooked

on all sides by the crumbling high-rise apartment buildings of East Pyongyang.

At the entrance to the compound was an armed soldier who stood on the

corner watching every car coming in and out. Beside him was a conspicuous

red telephone. Beyond, manned roadside guard posts appeared every hundred