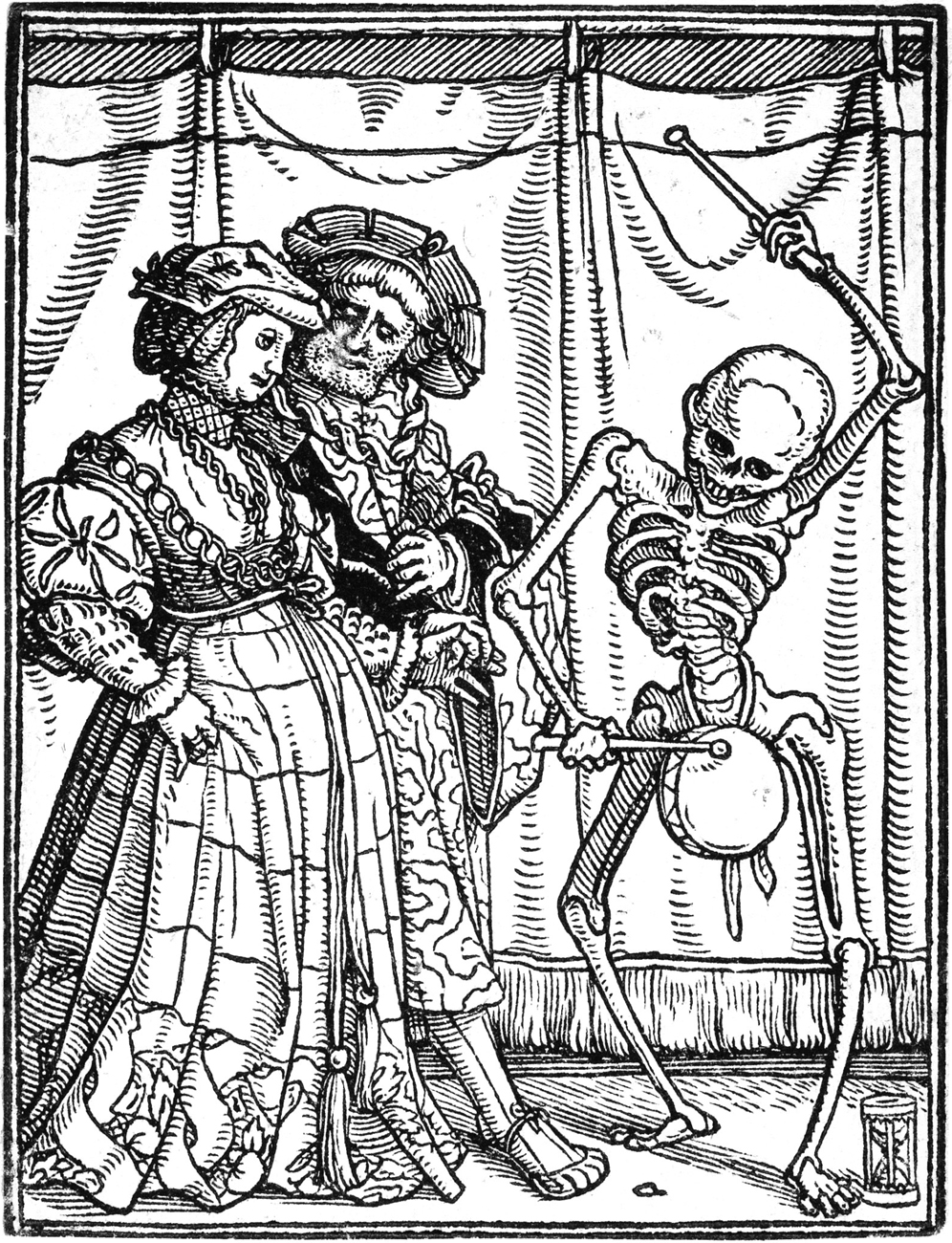

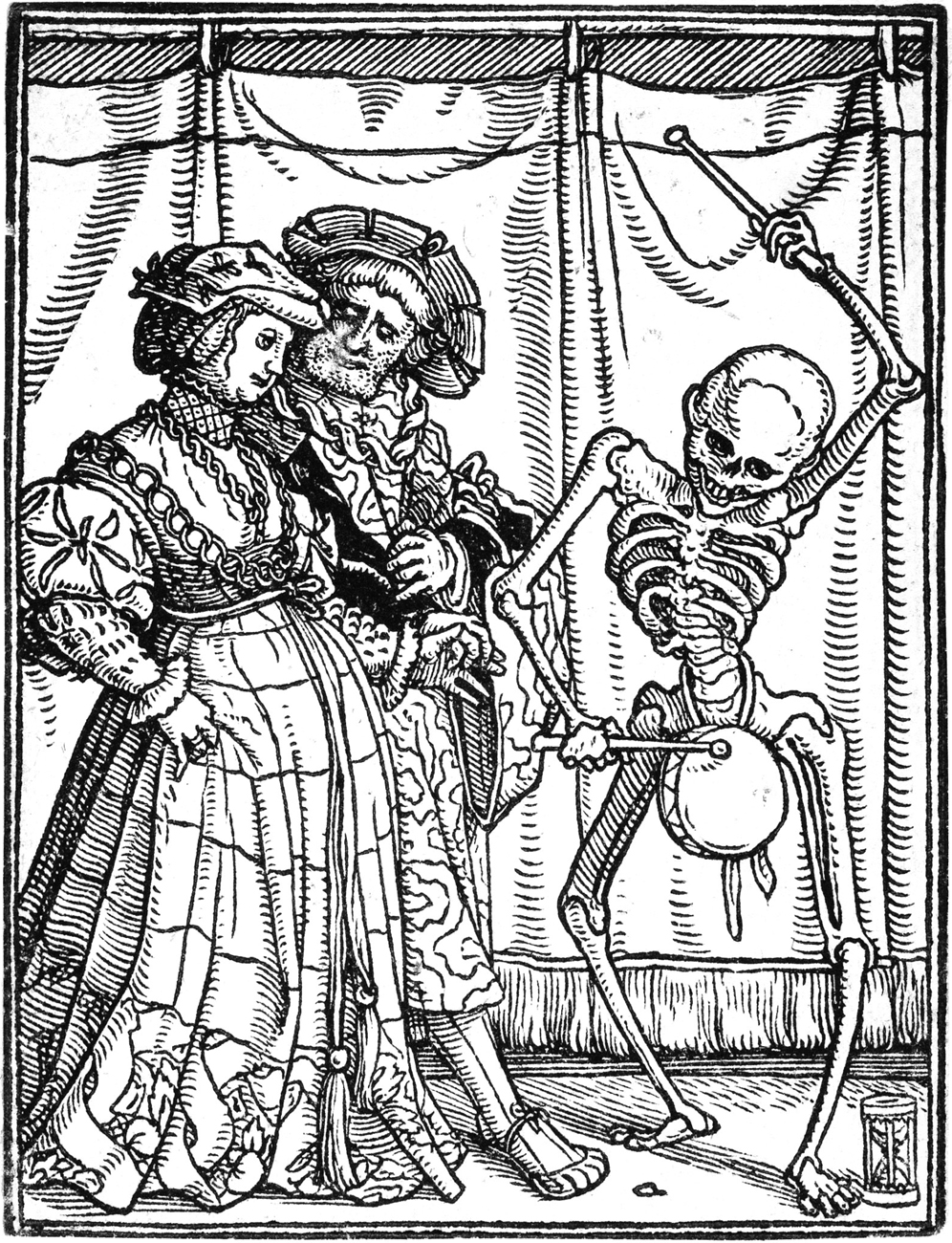

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Bridal Pair, from the woodblock series The Dance of Death, c. 1526.

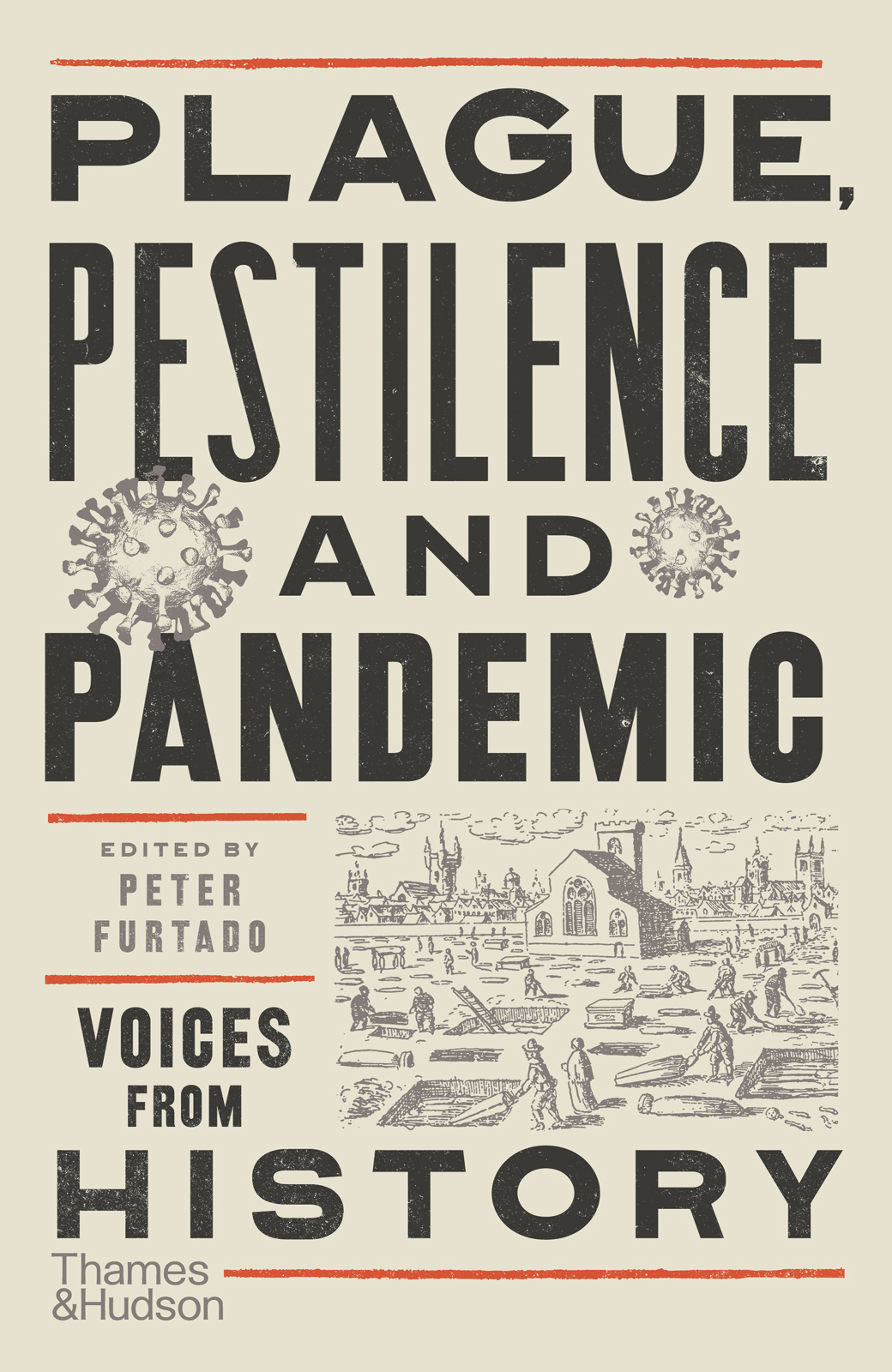

About the Editor:

Peter Furtado is the editor of the Sunday Times bestselling Histories of Nations, History Day by Day, Revolutions and Great Cities Through Travellers Eyes. He is the former editor of History Today.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Histories of Nations: How Their Identities Were Forged

Edited by Peter Furtado

Great Cities Through Travellers Eyes

Edited by Peter Furtado

History Day by Day: 366 Voices from the Past

Edited by Peter Furtado

Revolutions: How They Changed History and What They Mean Today

Edited by Peter Furtado

The Sick Rose

Or; Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration

Richard Barnett

Be the first to know about our new releases,

exclusive content and author events by visiting

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com.au

CONTENTS

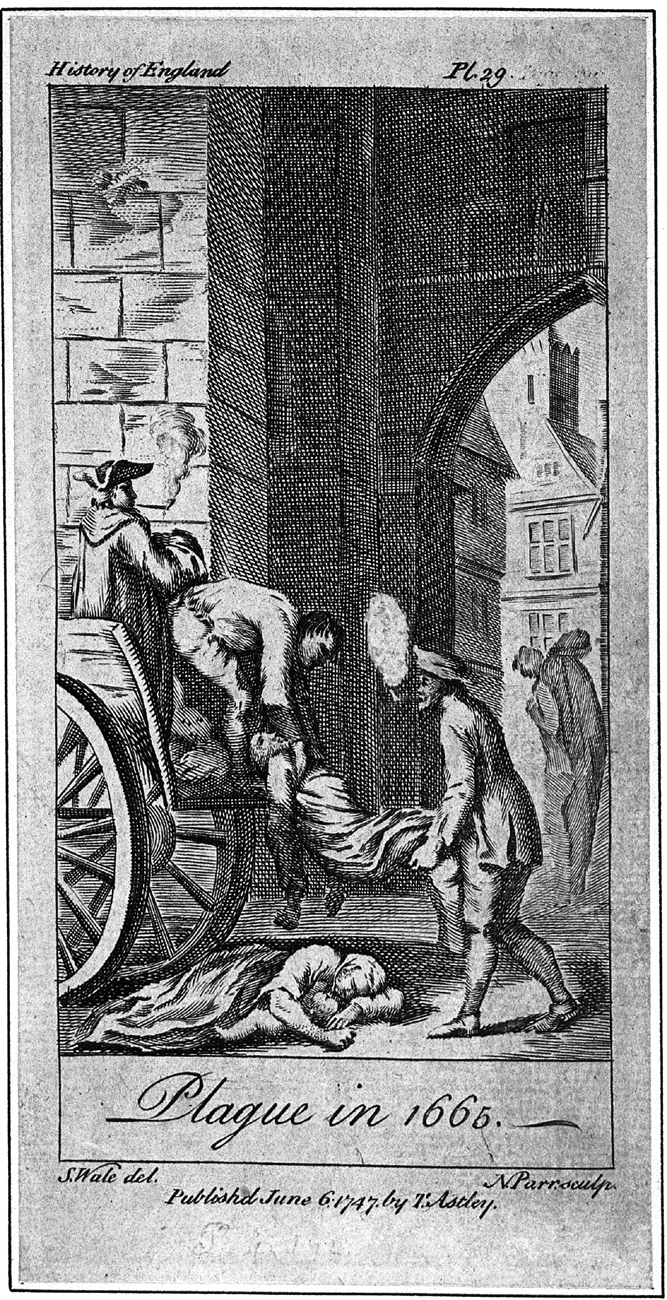

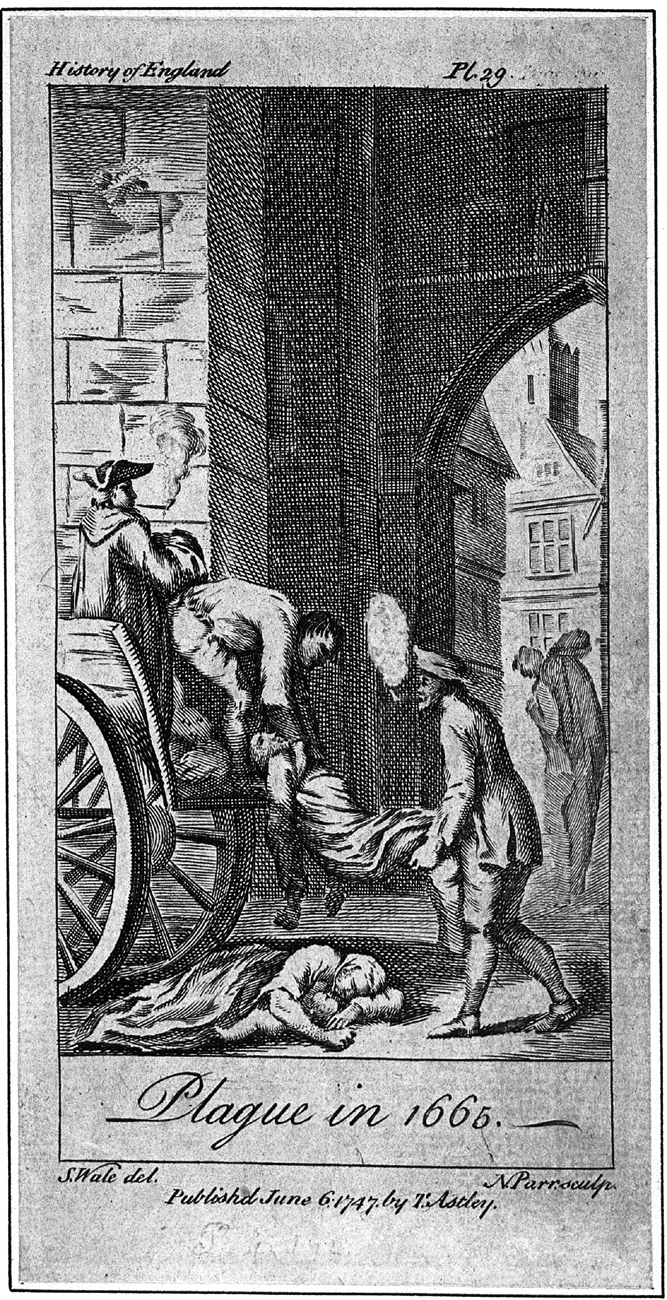

Victims of the City of Londons Great Plague of 1665 are lifted onto a death cart. Engraving by Nathaniel Parr after Samuel Wale, 1747.

Disease has always been with us. Epidemics and pandemics, less so.

To cause an epidemic, an infectious pathogen requires a population sufficiently settled and tightly grouped to allow it to spread from person to person. Yet settled populations eventually become familiar with the dangers that surround them; they acquire a degree of physical immunity to, or develop behaviours that mean they do not come into contact with, the most threatening pathogens. This means it is rare for a sudden epidemic of these local infective agents to sweep through them. Instead, epidemics plagues in the most general sense of the term, a sense that was established by the men who translated the Bible into English in the 16th and 17th centuries occur where enough people move far enough to encounter unfamiliar bacteria, viruses or parasites. They are historical events.

Even more so, a pandemic that causes widespread disease and death, bringing serious disruption to societies and their economies regionally or even globally, is not just a human tragedy or a medical event. It is one of historical importance. This will surprise no one who has seen how Covid-19, which has killed well over a million people and infected scores of millions, has also significantly affected the lives of the vast majority of the eight billion people on the planet, even those who have not been directly touched by the virus itself. Covid-19 will change history.

By contrast, the most deadly pandemic of modern times, which killed an estimated fifty million worldwide equivalent to the entire population of England in 2020, and somewhat more than that of California left surprisingly little trace on history. Its peak, in Europe at least, coincided with the final weeks of the First World War, and brought fear and tragedy to countless households, many of which had already suffered the loss of husbands, sons, brothers and lovers. It almost killed British prime minister David Lloyd George, and it permanently weakened the constitution of US president Woodrow Wilson, at a critical juncture of the Paris Peace Conference, which was reshaping Europe in the hopes of preventing another war. Yet the so-called Spanish flu of 191820 was a strangely private affair. Its hundreds of thousands of individual miseries took place behind closed doors and the press was restrained in its coverage. Health care workers and bus conductors wore masks and cinemas spaced out their performances to allow the air to be refreshed, but workplaces and town centres remained busy and there was no lockdown. No one blamed the flu for causing recession. No one suggested that those hundreds of thousands who died from flu were our glorious dead, or should be commemorated as the men blown apart on the Western Front were to be commemorated. The whole pandemic was soon forgotten, little more than a sad footnote to the more public tragedy of the Great War.

Even at the time of the flu epidemic, however, the men and women at the heart of the battle recognized that it was not an act of God but a product of a modern, industrialized world in which people moved at speed right across the globe, and often mixed in close proximity and under war conditions at least in considerable squalor. This disease, which is now thought to have been incubated in the military camps of the United States and northern France, was a product of historical forces closely related to those that had brought about the war itself. There was much to be learned from it not only what caused it (the flu virus was not isolated until the 1930s), how to treat it, how it spread and how to prevent or slow that spread, but also how a pandemic was becoming part of 20th-century life, something for which governments and medical authorities increasingly could and should plan.

Thus, in December 1918, American physician George Price described the Spanish flu as both destroyer and teacher. While those with a professional interest in public health, like Price, have sought to learn the lessons from past pandemics and prepare, with stuttering, intermittent success, for the next, they have not always had the consistent moral, logistical and financial backing of their political bosses, who have often paid less heed to what past pandemics might have taught them. When, in April 2020 and in the heat of the Covid-19 pandemic, US president Donald Trump defunded the World Health Organization, he gave the most dramatic instance of the short-sightedness of some elected politicians in preparing for, and understanding, the unpredictable but massive impact of the arrival of a novel pathogen within their borders.

The 20th and 21st centuries have produced great medical and scientific advances. Pathogens (bacteria and viruses) are understood in extraordinary detail, their life cycles, genetic structures, biochemistry and infection pathways quickly identified, their effects on those who are infected soon mastered. Antibiotics or antivirals to defeat the pathogens or mitigate their impact, vaccines to prevent infections and treatments to alleviate symptoms are widely available or are developed with astonishing speed. In parallel with this scientific progress has been the development of public health, nationally and internationally, which has brought unparalleled cooperations between countries and means that some diseases, such as smallpox and polio, have been, or are close to being, wholly eradicated in the wild.

In the light of this amazing explosion of understanding, one might have thought that pandemics would be a thing of the past. Indeed, in 1972 the Australian virologist Sir Macfarlane Burnet, who had won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1960 for his work on immunology, argued that the likely future of infectious disease would be very dull. He acknowledged there might possibly be some wholly unexpected emergence of a new and dangerous infectious disease, but nothing of the sort has marked the last fifty years. The field, he implied, was basically done and dusted.

Next page