QUAKERS

Peter Furtado

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

WHO ARE THE QUAKERS?

I F QUAKERS were not strictly pacifist, they could be described as consistently punching above their weight. A small sect currently fewer than 20,000 members in the UK and just 100,000 in the US has produced a disproportionate number of eminent thinkers, scientists and businessmen, as well as radical ideas that go on to be adopted by the mainstream. Among their number can be counted two US presidents (and one First Lady), several Nobel prize-winners, writers, actors and musicians, philanthropists, reformers, campaigners, educators, economists the list goes on and on.

Quakers have affected daily life in other ways. They are associated with some of the worlds best-known consumer brands, especially for confectionery (Cadburys, Rowntrees and Frys), although the jovial Quaker on the familiar oats package is a marketing invention rather than a historical individual. It is true, though, that a Quaker developed the board game Monopoly (as an educational activity to teach the perils of landlordism).

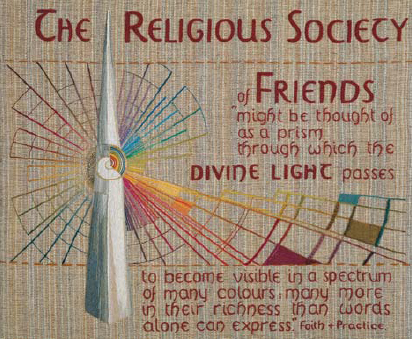

The divine light, as represented in one of the seventy-seven panels of the Quaker Tapestry, created in the 1980s and 90s, and now in a museum in Kendal. More than 4,000 men, women and children in fifteen countries had a hand in its creation.

Irving and Dorothy Stowe, two of the founders of the environmental direct-action campaigning group Greenpeace, were greatly influenced by Quakerism. The first voyage on the ship Greenpeace was to stop nuclear testing in the Pacific in 1971.

Quakers have been at the forefront of campaigns for peace and social justice all around the world. Once the leaders of the fight against slavery on three continents, in recent decades they have worked tirelessly with the United Nations and many other international bodies, NGOs and charities seeking to bring an end to the worlds most intractable conflicts, fighting poverty, campaigning against war and helping those whose lives are blighted by violence, whatever its source.

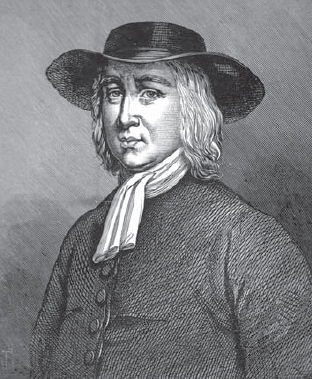

While it is not hard to point to what Quakers do, and the difference they have made to the world, it is much more difficult to pin down what Quakers believe. We can state, simply, what Quakers are: they are members of the Religious Society of Friends, a group that emerged in mid-seventeenth-century England as a fresh and personal expression of the teaching of Christ and the God of the Bible. It was founded by a shoemaker from Leicestershire, George Fox, who preached that every man, woman and child could have a direct experience of God within simply by listening and thus priests, hierarchies, sacraments or rituals all served to obstruct this experience. He also urged people to tremble in the face of the Lord a phrase taken up by a hostile judge in 1650 who jeered at Fox and his followers as Quakers. The name stuck.

George Fox also refused to impose a hierarchy or formal leadership on his Society, nor was there any kind of creed that a Quaker had to sign up to with the result that many Quakers no longer see themselves as Christians in the sense of believing in the saving power of the resurrection of Christ. Instead there is a confusing diversity of belief, practice and organisation within Quakerism. In some countries there is a single body that represents most Quakers living there (in Britain this is known as Britain Yearly Meeting); but elsewhere there may be many such Yearly Meetings, representing geographical, historical or theological diversity: in the United States alone there are more than thirty. As a result, modern Quakers beliefs are very varied, as are the various churches Meetings around the world. Some Quakers are socially conservative evangelical Christians; others are liberal in politics and plural in belief with Quaker Jews, Buddhists and Muslims, as well as Quaker theists (universalists) and even Quaker atheists, standing alongside those who recognise the Christian God that Fox taught. Consecrated churches are rejected, and in earlier times Quakers resisted the expectation that they would pay tithes to finance the steeple-house (church) and its professor (priest). Nevertheless, Quakers sometimes have professional or paid ministers, and in some traditions these are crucial to the life of their church.

The emphasis on the inner light, on the direct experience of God, led early Quakers to adopt a unique form of worship. Instead of services, they held Meetings for Worship, sitting in silence (broken by occasional spontaneous ministries from members), waiting and listening for the word of God to show the way forward. Sitting in silence is not universal, however: some Quaker Meetings have structured services that include hymns, psalms and prayers. Yet sitting together in expectant silence is cherished by Quakers across the globe, and is often seen as the distinctively Quaker practice.

Brigflatts Meeting House, in Cumbria, built in 1675, is typical of the modest Quaker Meeting Houses of Britain and New England. Unlike churches, Meeting Houses are not considered more sanctified places than anywhere else.

A French view of a Quaker Meeting in the very early eighteenth century, showing a woman preaching from the balcony.

William Penn was a leading Quaker propagandist in the 1670s, and established the US state of Pennsylvania with an idealistic constitution in the 1680s.

Quakers apply similar principles to the running of their affairs. Business meetings are known as Meetings for Worship for Business, and are conducted in silence, broken by measured interventions. No votes are taken and no decisions made until there is a sense of the will of God in the room. This sense is meticulously summed up in a written minute that is agreed by the whole meeting. The process, which can admittedly be slow, is inclusive and often creative.

Instead of a formal creed, Quakers share an understanding, ethic and code of conduct, which is summed up in two volumes Advices and Queries, a slim set of aphorisms and questions which are regularly read and discussed, and the Book of Discipline, which sets out the regulations for the right ordering (proper running) of the Meeting and includes many short, inspirational quotations collected from Quakers over the centuries. Neither volume is set in stone, but is regularly reviewed and updated a process of true collaboration involving all who wish to take part.