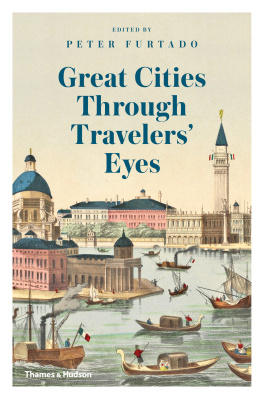

About the author

Peter Furtado has edited a number of bestselling history books including Histories of Nations: How Their Identities Were Forged and 1001 Days That Shaped the World. He was editor of History Today magazine from 1998 to 2008 and in 2009 was awarded a DLitt by Oxford Brookes University for his contribution to the popularization of history.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Histories of Nations: How Their Identities Were Forged

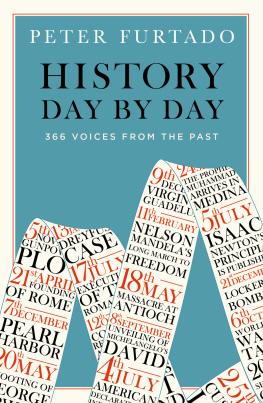

History Day by Day: 366 Voices from the Past

The Great Cities in History

Cities That Shaped the Ancient World

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

A city can be all things to all people. One person will find myriad opportunities for profit and advancement where another sees nothing but a crowded cacophony of pressing humanity. One person sees the city as a seat of government and law, the opportunity to display unchallengeable power, while another sees it as a place of freedom and anonymity. A city can be the location for cultural or spiritual expression, a destination for people seeking meaning in their lives, or a place of crass and oppressive materialism; a playground for those with spectacular wealth, or a prison for those suffering unimaginable poverty and pain. Cities are sites of decisive conflict: wars and revolutions are decided by whether key cities fall or resist attack.

It has ever been thus. Today, almost half of us live in cities, and the rest of us rely on them to some degree. But cities have been with us for thousands of years, and they have nurtured civilization itself. Places like Ur and Sumer in Mesopotamia, Damascus and Jericho in the Levant, Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in the Indus Valley, Erlitou and Luoyang in China and Tres Zapotes and Chavn de Huntar in the Americas the growth of these towns marks the development of a complex society with its own identity and organization that dominated the region around and led to the emergence of the worlds first civilizations. Our very word civilization derives from civis, the Latin word for a citizen or inhabitant of a city.

Cities cannot exist in isolation from the world around them. Every day, people from the surrounding countryside have come and gone through the citys gates, bringing raw materials, produce or labour, and returning with cash or goods, perhaps luxuries that can only be found where craftspeople and traders congregate. Cities send out soldiers to dominate surrounding regions or conquer other cities, traders to bring back precious goods, emissaries to seek knowledge or build connections with others. Cities attract visitors, sometimes from distant lands; and even if some cities have been devastated or even eradicated by the attentions of enemy armies from afar, others are endowed with sights distinctive enough to make a special journey worthwhile and can thrive on peaceful pilgrims or tourists enduring long and arduous journeys to see them.

And many cities Damascus, Rome, Athens come to mind are among the most truly enduring the most alive of all historical artefacts, not only preserved as museum pieces but remaining vital for thousands of years, each with a unique identity and appeal that has changed and grown with the vicissitudes of the centuries. The cultural and physical edifices of such cities are a palimpsest or patchwork of historical legacy and modern need. Over the centuries, they have seen all kinds of visitor sometimes welcome, sometimes less so.

But whether a city is predominantly antique or entirely modern, travellers are frequently impressed and amazed by what they find. Whoever has made a long and difficult journey to a city will arrive full of expectation and attention, alert to whatever is impressive, strange or new. And what the visitor sees depends not just on what exists there to be seen, but on their own expectations and interests. Some will experience a direct assault on the senses, a riot of colour, texture and sound, a barrage of smells; but others, arriving in the self-same place, may come so laden with preconceived ideas and associations that what they see exists almost entirely in their imagination. Some visitors arrive in an unknown city and notice its buildings and streets, its government, its organization and the way that it treats the new arrival; a different visitor will be struck by the faces, voices and gestures of the men and women who live there, and note glimpses of unfamiliar ways of life, mysterious, alluring or even frightening.

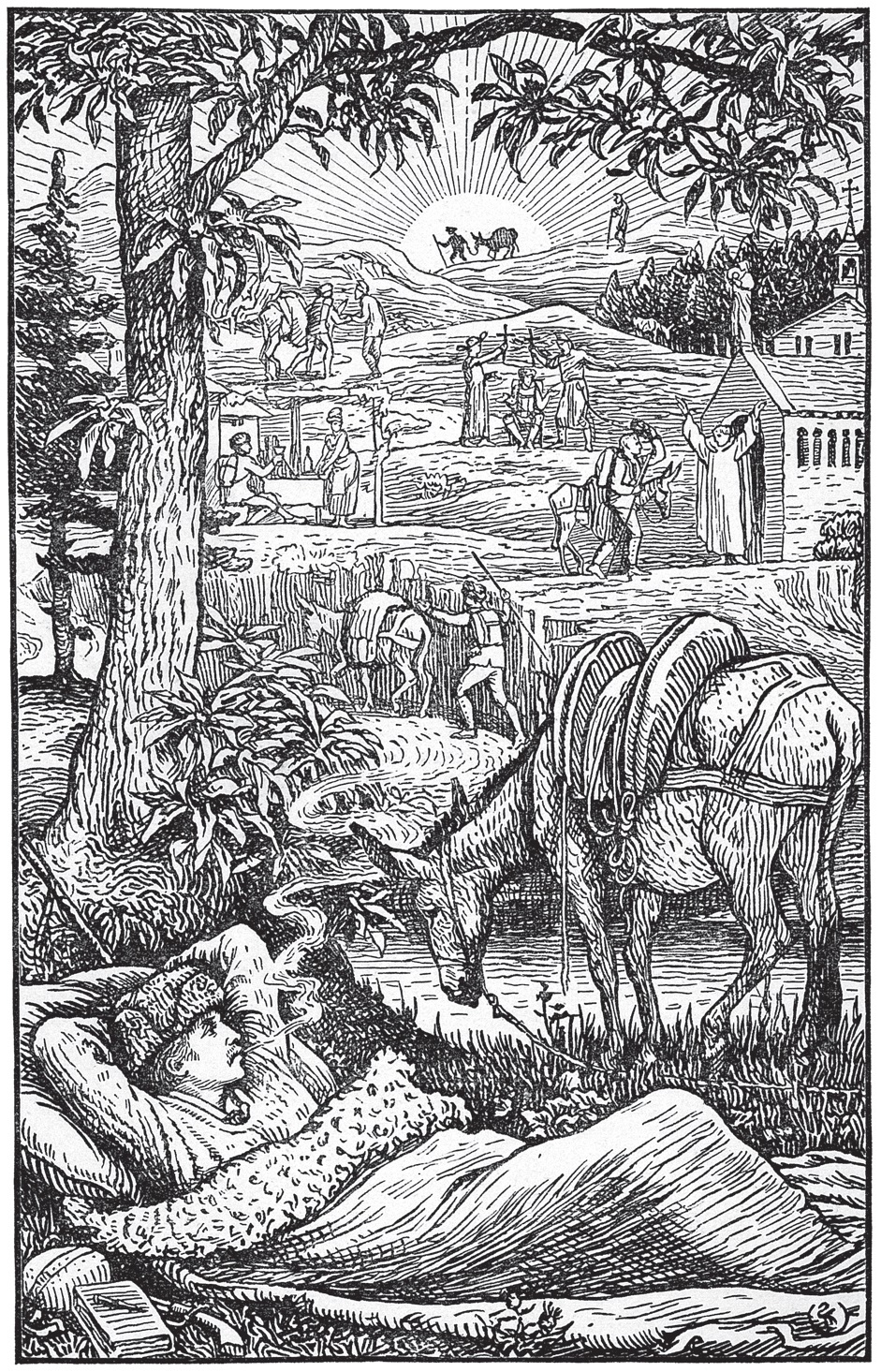

Some of those travellers who see and feel this heightened excitement, this novelty, this danger that only the city can bring, have captured their experience in words and pictures. When set down immediately in diaries and letters, the urgency can burn off the page; even when written down months or years later in memoirs or reports, the picture can have greater polish, yet be all the more vivid for that. Then there are the travellers whose personal experiences and insights are transmuted into the universality of poetry or fiction.

The earliest accounts of travellers encountering alien cities are found in religious and epic texts: Joshua outside the walls of Jericho, the Achaeans at Troy. But memorable though the verses of the Bible and Homer may be, they are not the words of Joshua and Achilles themselves. And even in the Classical world, there are rather few descriptions of cities and visits to them, and those that do exist tend to be brief for example, the earliest mention of Paris comes from the Roman soldier Julian, who was proclaimed emperor there in AD 361; his comment, though memorable, used just two words, cara [sweet] Lutetia, using the name the Romans gave to their settlement by the Seine. Herodotus, who was a great traveller, tended to write about the peoples he encountered, not the places he went. Conversely, geographers like Strabo gave more detailed though often dry factual accounts of cities, and it is rare to find indications they had personally visited the places in question.

It was only in Europes Middle Ages that a genre of writing akin to travel literature arose, initially with books written by and for pilgrims to the great religious sites, especially Jerusalem and Rome. But at the same time, Muslim writers wrote about their travels, among them the greatest pre-modern traveller of all, the Moroccan Ibn Battuta, who covered more than 70,000 miles over thirty years in the mid-14th century, and who gave detailed and personal accounts of the people he met, the places he went and the hardships of getting to them. These centuries, when the Silk Road was at its height, also saw a steady trickle of travellers from Europe to China (most famously Marco Polo, whose account of his travels became Europes first-ever bestselling book), as well as in the other direction, including the Chinese Christian monk Rabban Bar Sauma, who wrote vividly about his visit to western Europe in the 13th century.

Travel literature as we know it whether we mean books written to assist the prospective traveller, self-aware accounts of travelling or reports of significant journeys became more common from the 16th century. Whether it was the European exploration and colonization of the world, the increasing scope of commercial and military activities in distant climes, the advent of the Grand Tour and other cultural or intellectual journeying, the dispersal of imperial personnel to their postings around the world or the development of mass tourism, all these and many more personal motives made travelling, and writing about travelling, a rich seam for writers and readers to mine.

Next page