CHAPTER 1

New Money, Old Ideas

In the 19th century taste was a weapon in the war between the new mercantile middle and the old gentry.

Simon Heffer, High Minds: The Victorians and the Birth of Modern Britain, 2013

T he late 18th century had a taste for revolution. The American Revolutionary War set the stage for the French Revolution which, in turn, inspired a century and more of unrest across Europe. Less violent but every bit as seismic and systemic was Britains Industrial Revolution, which changed the countrys economic and social templates and gave the rest of the world a model for a post-agrarian society.

In the early 19th century Britain ruled the waves and its collection of colonies and trading quangos provided the raw materials and the markets that underpinned its economic and political pre-eminence. That supremacy would not be challenged until the modest coastal strip, wrested from it by tax-phobic colonial rebels, grew to become the United States of America and to dominate the 20th century.

The French Revolution worried Britains ruling classes. A few idealists, like William Wordsworth, pursued the chimera of liberty, equality and fraternity and visited the new French utopia, only to retreat before the brutalities of the revolutionaries reign of terror. In 1799 Napoleon Bonaparte dispatched the revolutionary rump, established the First Empire and, having awarded himself the title of Emperor, embarked, with his grand arme on his grand projet, on the conquest of Europe. Britain dispatched Wellington and Nelson to deal with him and their victories encouraged her presumption that she ruled the world.

Frances revolution had been partly precipitated by taxes levied on the peasantry but in Britain the relative prosperity of those deserting the uncertainties of agricultural labour for the meagre but reliable subsistence of factory work diffused the likelihood of rebellion. The last of Britains Hanoverian monarchs, mad George III and the foppish Prince Regent (later George IV), were considered too absurd to be worth the trouble of hanging.

As more immediate Georgian heirs died without legitimate issue in 1837 the 18-year-old Princess Victoria ascended to the throne. Her youth and gender perhaps suggested a new beginning and her overt piety and enthusiasm for domestic bliss matched a change in the national mood. Her name came to embody the mores that defined the 19th century in Britain and, perhaps curiously given its blossoming republicanism, in the United States. With the virtues of hindsight, the period is castigated as a time when the poor were mercilessly exploited but Simon Heffer offers a more nuanced perception: Although poverty, disease, ignorance, squalor and injustice were far from eliminated, they were beaten back more in those 40 years or so years [18401880] than at any time in the previous history of Britain, a nation that might have been overwhelmed by industrial change, rapid expansion and social upheaval instead saw the challenges of modernism and embraced them. While Britains creative entrepreneurs like Isambard Kingdom Brunel who built railways and ships, bridges and tunnels and Joseph Bazalgette who designed and built the sewage system that rescued London from its own effluent set about shaping the countrys future, her architects and artists were more inclined to shy away from unedifying modernity and to take refuge in the principles and practices of an idealised Middle Ages.

The Georgian Neo-Classicism of the late 18th century was beginning to look a little too continental for the island race. France was happy to find architectural inspiration in the pagan models of Classical Greece and Rome but Britain turned to something Christian that might, just, be considered indigenous. Gothic architecture might have originated in 12th-century France but England, in its Late Medieval churches and cathedrals, had evolved its own structurally and decoratively complex Gothic traditions which could and would be adapted to serve a diversity of secular functions that were exclusively of the 19th century.

The ascension of the new queen encouraged an extraordinary enthusiasm for religious debate and practice. It was generally assumed that the success of the country, and its empire, was built on Christian values. In his painting The Secret of Englands Greatness, Thomas Jones Barker depicted Victoria handing a bible the handbook for virtuous and civilised behaviour and the prosperity that would follow it to a kneeling African. Anglicanism remained the state religion but in its internal doctrinal disputes a significant faction of its adherents veered towards more austere personal conduct while paradoxically advocating the more flamboyant ceremonial trappings that were closer to Roman Catholic practices. The Church of England acted as the arbiter of national mores but its primacy was challenged. As industry brought wealth and comparative prosperity to the provincial strongholds of non-conformity, a more proscriptive morality asserted itself, every bit as austere in matters of personal conduct but with a decidedly Protestant suspicion of ceremony. While bishops debated the origins of humankind with Darwin and his acolytes, itinerant evange-lists were drawing enormous and excited audiences across the country to rallies that were catalysts for the conversion of huge swathes of the population to a benign fundamentalism. Charismatic preachers expounded the finer points of doctrine, but they were also non-violent revolutionaries who condemned social injustices.

Churches were the nuclei of social life. Governments, anxious about revolution amongst workers crammed into brutal factories and foul slums, financed the building and refurbishment of 2859 Anglican churches between 1841 and 1870 to strengthen the restraining hand of religion. Not attending church risked social exclusion at higher social levels and the chances of employment at the lowest. It could be a vicious circle: in his London Labour and the London Poor Henry Mayhew cited a slum-dwelling labourer who said my wife and children can go to chapel at certain times, when work is pretty good and our things are not in pawn.

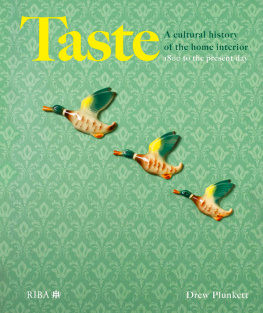

Piety needed displays of decency and, for everyone other than the very poor, home furnishings represented tangible evidence of decency. In Turning Houses Into Homes Clive Edwards wrote: The home is both an idea and a reality a symbolic environment representing ones identity through the things therein.) its followers were increasingly inclined to see conspicuous consumption as proof of piety and propriety. Sudden wealth, however modest, and the extravaganza of factory-produced ornaments that might crowd the mantelpieces and whatnots of homes great and small was too much for all but the stoutest spirits. The perfectly human instinct for virtuous prettification was too strong for all but the most abstemious anchorites.

Edwards also suggested that as people moved from cottage industries to working in factories and offices, their homes became places of rest and recreation The exercise of taste is a delicate matter.

The architectural historian Mark Girouard saw the accumulation of ornaments as a national psychosis because there was more money in more pockets the surfeit was being spent on what were, strictly speaking, non-essentials. However, the appetite for ornament might suggest that, when shelter and food are secured, ornament becomes a necessity and the relentless churning out of inexpensive, mass-produced decorative objects puts temptation in householders way. He concluded that collecting something or other became a nineteenth century craze, not just one confined to the dilettanti. The nature of objects accumulated was presumed to confirm that one was serious about ones taste: the more one accumulated, in emulation of the myriad monkeys who might type a Shakespearean phrase or two, the more likely one was by default to offer some evidence of deserving ones place in the social order.