Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East Seventh Street

New York, New York 10003

Visit our website at www.papress.com.

2012 Princeton Architectural Press

All rights reserved

Printed and bound in China

15 14 13 12 4 3 2 1 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editor: Megan Carey

Designer: Jan Haux

Special thanks to: Bree Anne Apperley, Sara Bader, Nicola Bednarek Brower, Janet Behning, Fannie Bushin, Carina Cha, Tom Cho, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Russell Fernandez, Linda Lee, Gina Morrow, John Myers, Katharine Myers, Margaret Rogalski, Dan Simon, Andrew Stepanian, Jennifer Thompson, Paul Wagner, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

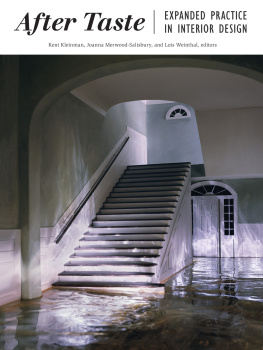

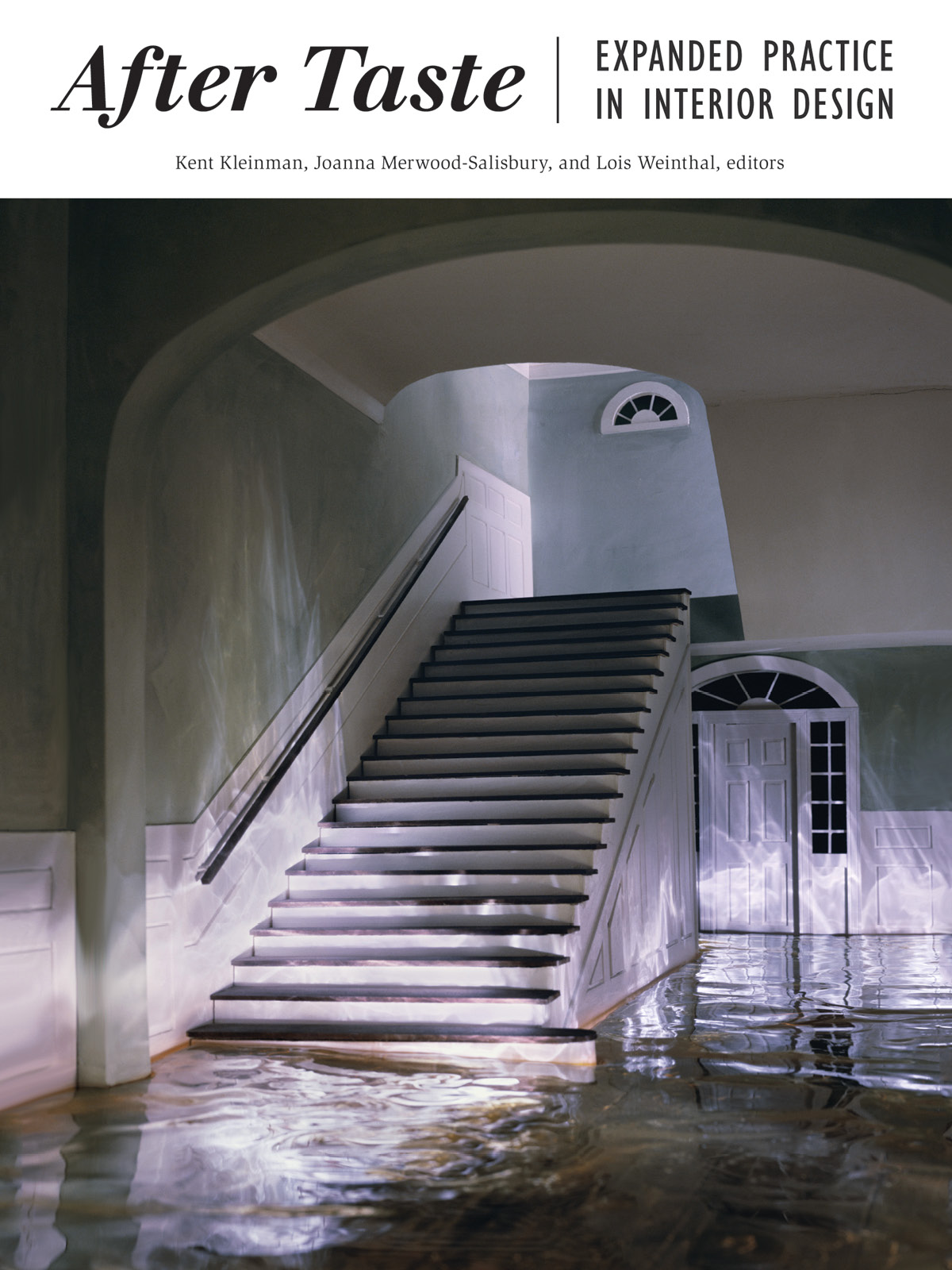

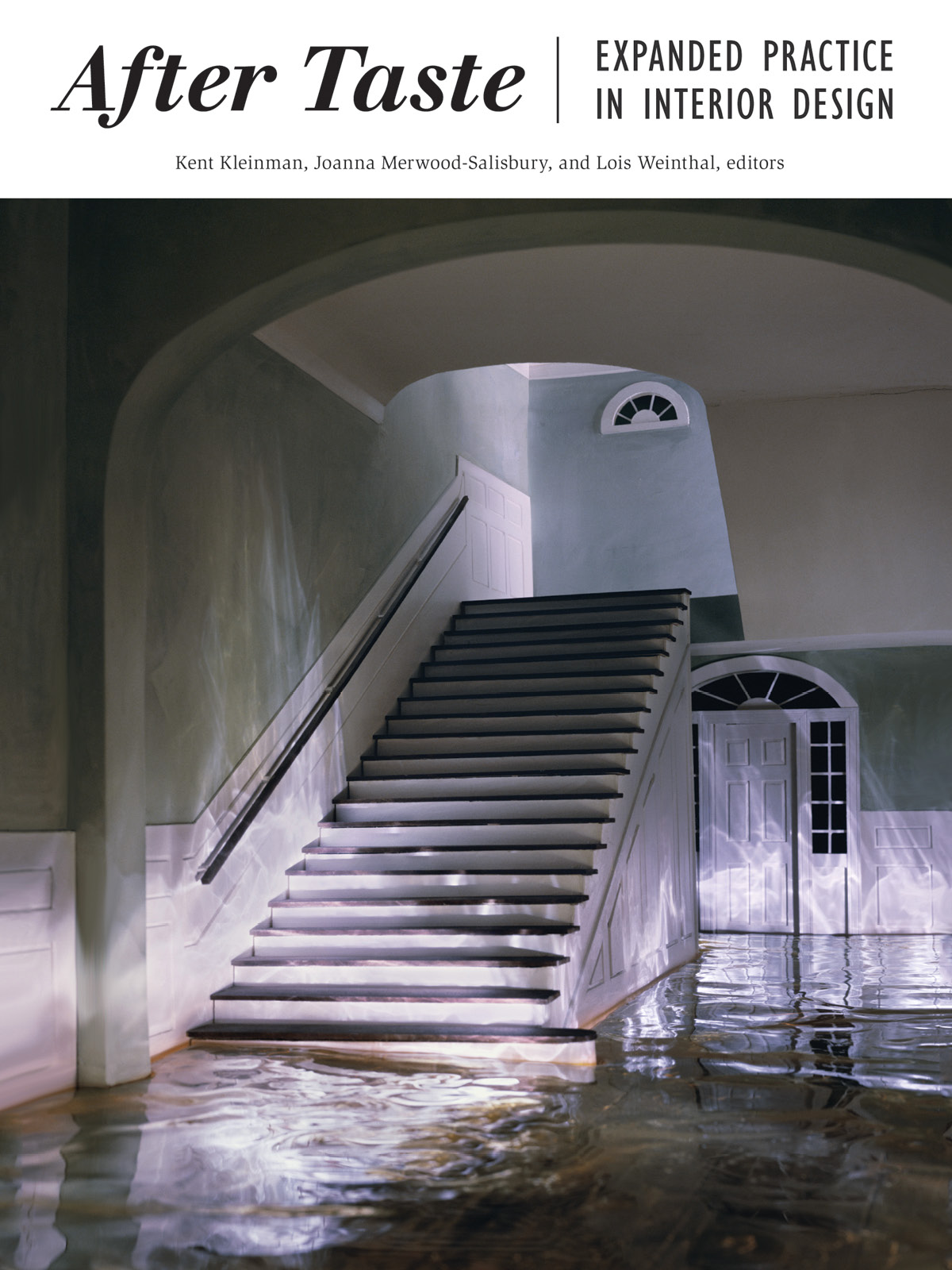

Front cover image:

James Casebere, Green Staircase #1 , 2001. Digital chromogenic print. 60 x 48 inches and 96 x 77 inches. Copyright James Casebere. Courtesy of James Casebere and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

Back cover image, left:

Courtney Smith, Bonito , 2002. Cabinet and hand carving. Collection of Elizabeth Moore, New York. Photograph by Rodrigo Pereda

Back cover image, right:

Petra Blaisse, Villa Leefdaal, Leefdaal, Belgium, 20034. Living room with curtain pulled closed meeting the glass wall and landscape. Courtesy of Inside Outside

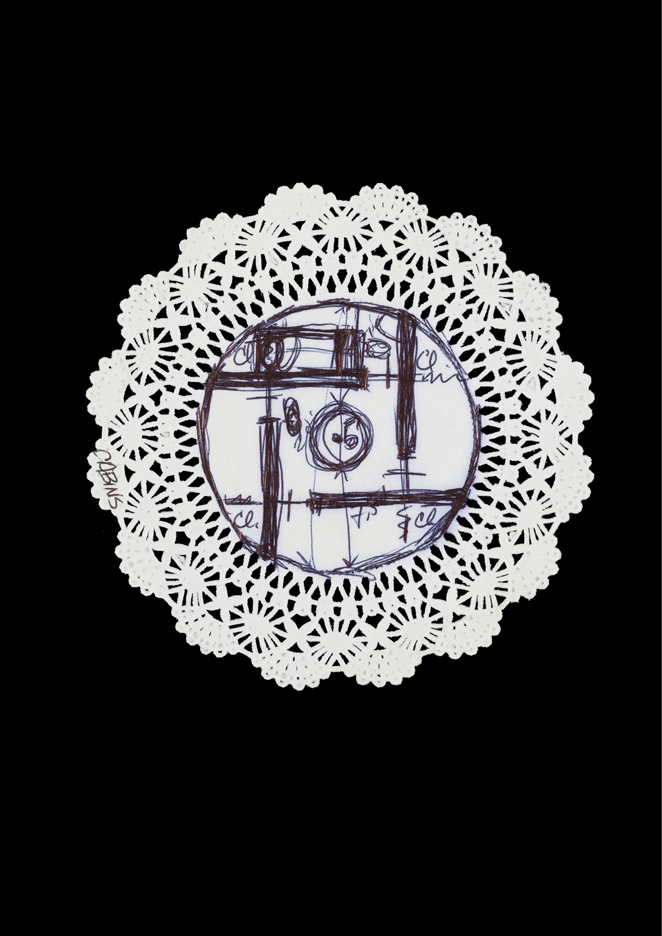

Frontispiece image:

Planning study for space optimization in a vertically oriented, cylindrical International Space Station module, 1997. Courtesy of Constance Adams

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

After taste : expanded practice in interior design / edited by Kent Kleinman, Joanna Merwood-Salisbury, and Lois Weinthal. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-61689-026-1 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61689-139-8(digital)

1. Interior decoration. I. Kleinman, Kent, 1956 II. Merwood-Salisbury, Joanna. III. Weinthal, Lois. IV. Title: Expanded practice in interior design.

NK2125.A39 2011

747dc22

2011010530

After Taste

EXPANDED PRACTICE

IN INTERIOR DESIGN

Kent Kleinman,

Joanna Merwood-Salisbury,

and Lois Weinthal, editors

Princeton Architectural Press

New York

Introduction

Kent Kleinman, Joanna Merwood-Salisbury, and Lois Weinthal

Not only is th[e] accumulation of false richness unsavory, but above and before all, this taste for decorating everything around one is a false taste, an abominable little perversion.

Le Corbusier

[Nineteenth-century] society gradually killed any creative impulse with the poison of its ruling taste.

Sigfried Giedion

The repudiation of taste as a category by which to make and judge design is a defining trope of modern design criticism, and interior design is one of its primary targets. Starting in the eighteenth century the practice of designing interiors depended on the replication and display of highly coded aesthetic elements in order to signify intimate knowledge of the distinctions between social strata. For high modernist critics such as Le Corbusier and Sigfried Giedion, the techniques of this display were inherently suspicious, if not fundamentally flawed. Involving a surface application of decoration using the slippery feminine arts of disguise, interior design promoted architectural dishonesty and inauthenticity. For Giedion, the value of interior design was directly proportionate to its disappearance. In this rhetoric, interior design, viewed as a vehicle through which to communicate wealth and class affiliation, was a form of what economist Thorstein Veblen had labeled conspicuous consumption, something that signified only to the degree that it resisted being actually useful, since uselessness was the measure of discretionary wealth. In this sense, interior design is close to fashion, and taste is code that enables both to serve their stratifying functions.

In fact, the historic links between interior design and taste are probably impossible to erase: the creation and design of private space is essential to the construction of the modern social world and its manners. Indeed, one could say that the very purpose of interior design has been to demonstrate the prevailing taste. The inextricable interconnectedness of the two, along with the persistent gendering of interior design as feminine, has shaped both the vocational and intellectual development of the field. It has created a form of practice with highly specialized techniques, methods, and knowledge domains, a practice situated outside of architecture and outside of fine art but tangential to both. Intellectually, however, this partitioning has made it difficult for historians and critics of interior design to establish a theoretical framework for the field. Only recently, but rapidly multiplying, has there been critical and scholarly writing on interior design.

Despite the importance of taste to the formation and constitution of the discipline, it has not been subject to examination, with a few notable exceptions. The essays in this volume interrogate the idea of taste, its importance to the history and practice of interior design (including emphatic attempts to reject it in the mid-twentieth century), before positing its continued usefulness in the field today, albeit in renewed terms. Our intent is to resist the temptation to examine the history and theory of the discipline through the lens of other fields (especially architecture, through which it will always be seen as inferior) and to leverage the philosophical concept central to interior designs own tradition.

Early versions of the essays collected here were presented at After Taste , an annual symposium series hosted by Parsons The New School of Design between 2007 and 2010. Created to provide an intellectual framework for a graduate program in interior design, this series was dedicated to the critical study of the interior, offering expansive views of interior studies, highlighting emerging areas of research, identifying allied practices, making public its under-explored territory, and attracting future designers and scholars to the field. When first conceived, the title was deliberately chosen to signal a move away from the popular image of interior design as a field of taste making and tastemakers. In the course of its short life, the After Taste project has continued to evolve. The purpose of this book is not to publish the proceedings of the symposium series but to edit, refine, and even challenge the premise of that forum. To our surprise, taste has emerged as an important and continually relevant intellectual framework. As one of these essays proposes, perhaps a better title is not After Taste , but After After Taste , or Taste, After All .

The book is organized into three sections. The first, On the Problem of Taste, investigates the historical connectedness between the discipline of interior design and the philosophical concept of taste. Beginning in the eighteenth century, the modern interior was established in parallel with the invention of the modern subject, a subject who occupies a separate and private realm apart from his or her public persona, both spatially and psychologically. The second, Expanded Pedagogies and Methods, maps the twentieth-century territory of interior design practice and pedagogy. The section pays special attention to attempts to redefine and expand the field of its operation beginning in the 1960s, attempts that embrace the social sciences and environmental psychology as well as new technologies of construction and representation, often in the service of inter- or transdisciplinarity. The final section, Practicing After Taste, gathers these diverse threads together focusing on some particular concerns within contemporary practice: accommodating shifting definitions of what is properly public and private; the problem of recognizing, recording, and preserving the ephemeral quality of interiors; and finally the terrestrial insights to be gained through the design of extraterrestrial interiors.

Next page