Contents

Page List

Guide

Cover

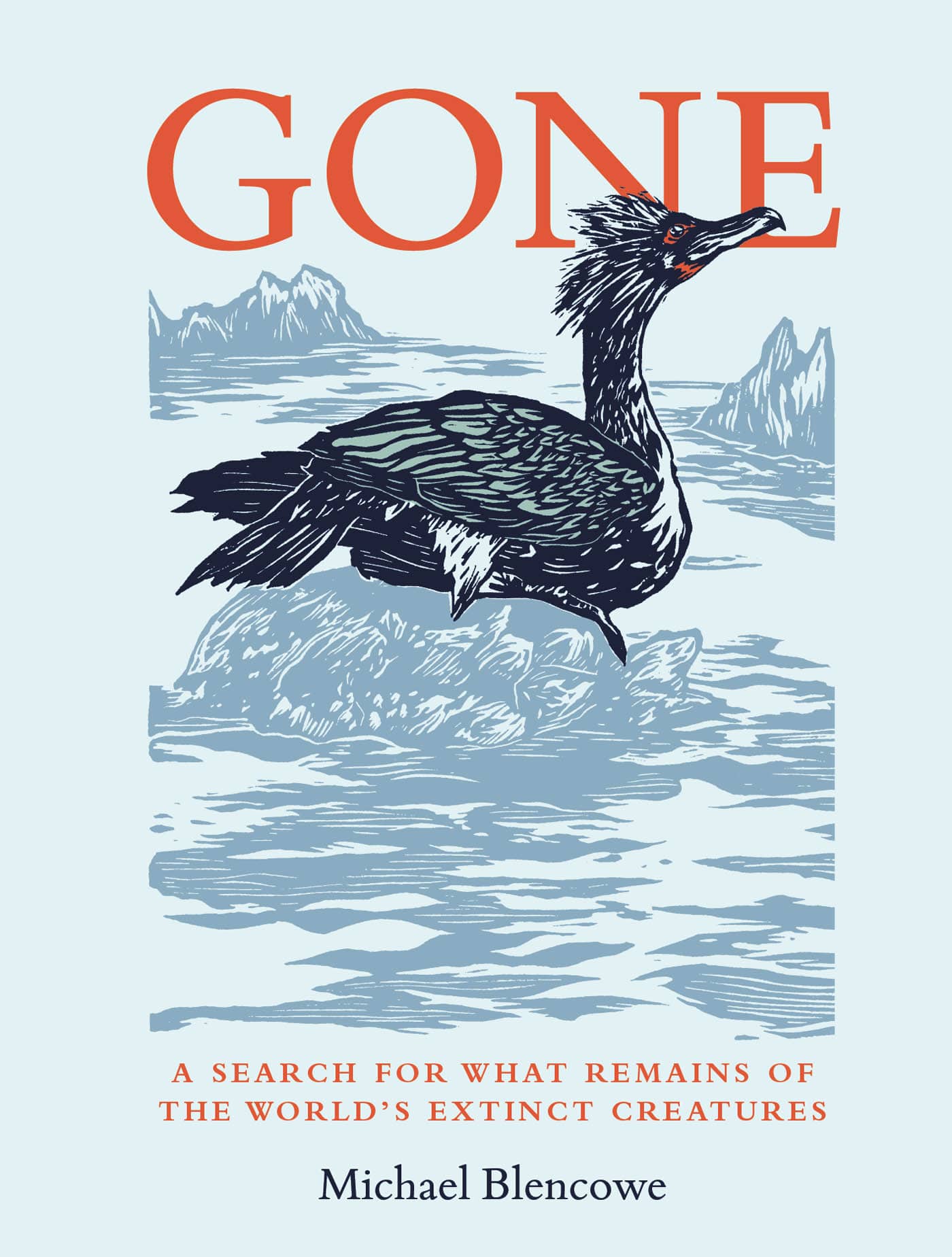

GONE

A SEARCH FOR WHAT REMAINS OF THE WORLDS EXTINCT CREATURES

Michael Blencowe

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Booth Museum of Natural History

Chapter One

Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)

Chapter Two

Spectacled Cormorant (Phalacrocorax perspicillatus)

Chapter Three

Stellers Sea Cow (Hydrodamalis gigas)

Chapter Four

Upland Moa (Megalapteryx didinus)

Chapter Five

Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris)

Chapter Six

South Island Kkako (Callaeas cinereus)

Chapter Seven

Xerces Blue (Glaucopsyche xerces)

Chapter Eight

Pinta Island Tortoise (Chelonoidis abingdonii)

Chapter Nine

Dodo (Raphus cucullatus)

Chapter Ten

Schomburgks Deer (Rucervus schomburgki)

Chapter Eleven

Ivells Sea Anemone (Edwardsia ivelli)

INTRODUCTION

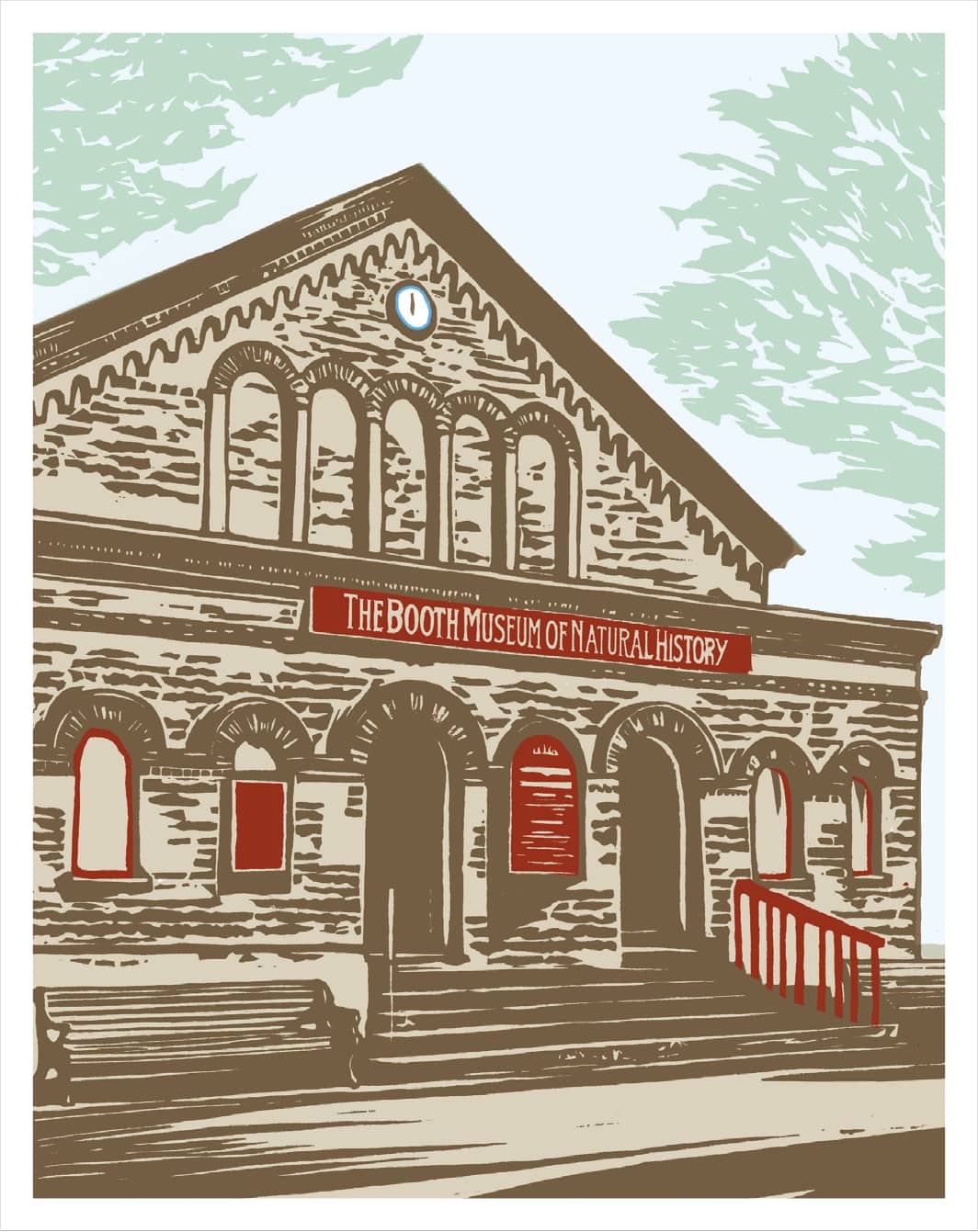

The Booth Museum of Natural History

The Booth Museum of Natural History

Three minutes to twelve. Its always three minutes to twelve.

Ive tried to stay hopeful, I really have, but Ive just never been able to shake the feeling that Im constantly living in the last moments of a countdown. My entire life Ive been shackled to the irrational belief that, at any second, the final whistles going to blow and my life will come crashing down around me. So, Ive always steered clear of long-term plans and avoided putting things off until tomorrow, just in case.

Switching on the news these days, my anxious foreboding seems less like a crazed state of mind and more like a reasonable response to the times were living in. When I was a child, I imagined the world to be vast, balanced and indestructible, but sat here watching forests burn and icecaps melt it seems vulnerable, fragile and somehow smaller.

If other people can see hope for the future, Im afraid I dont share their optimism. In fact, these days Im finding myself increasingly adrift, disconnected from the other 7.8 billion Homo sapiens on the planet. Ive started wondering whether I could defect from the human race altogether, maybe align myself with another species, one that doesnt seem hellbent on destroying the world. Aardvarks perhaps. They seem happy enough hiding away in a burrow all day, sneaking out at night to eat ants and cucumbers.

On those days when everything feels particularly hopeless, I always seem to find myself stood here, staring up at the weathered redbrick facade of this Victorian building. Set high above its embellished arches is a turquoise-rimmed clock. The time reads three minutes to twelve. It was three minutes to twelve when I first stood in this spot 30 years ago and, as far as anyone can recall, it has always been three minutes to twelve here. Not that I would want anybody to repair the rusted cogs and gears of that broken clock. Its motionless hands are just another of the many quirks that make this place so peculiar, so special, so timeless. For three decades this building has been my refuge against the world, and these days I need it more than ever. I step up through the bright red wooden doors and into the Booth Museum of Natural History. The world changes.

The Booth Museum exists in its own light, its own climate, its own time. I pause for a moment and close my eyes, soaking up the silence and allowing the world outside to fade away. Upon opening them I find the attendant at the front desk has lowered her paperback and is observing me suspiciously over the rim of her glasses. She nods a wary greeting, I respond with a smile and her thumb clicks the handheld tally counter adding me to todays total. Just another visitor at the Booth.

This extraordinary museum lurks unassumingly along Dyke Road, the tree-lined residential avenue that connects the coastal city of Brighton to one of Englands best-loved landscapes: the rolling chalk hills of Sussexs South Downs. The museum was built in 1874 by ornithologist Edward Booth. Booth loved birds and he enthusiastically pursued his passion with his double-barrelled eight-bore percussion shotgun with dolphin hammers and Damascus steel barrels. A display cabinet holds Booths gun along with the battered waterproof sandals and souwester he would pull on before tramping the wet marshes and moors hunting his quarry. His dream was to collect and display a specimen of every species of British bird in every plumage. Theres a posed photograph of Booth bearded, suited and steely-eyed staring off camera as if hes just caught sight of some elusive warbler that requires shooting, stuffing and displaying in his collection.

Born in 1840, three years after Queen Victoria ascended the throne, Booths behaviour, which today seems reprehensible, was typical of a nineteenth-century naturalist. Victorian society was enthralled by the natural world and they demonstrated their admiration through coveting, collecting and categorising it. Birds, butterflies, ferns, eggs, seaweeds, shells, you name it if the Victorians could get their hands on it, theyd kill it, skin it, stuff it, press it and pin it. Their collections and curios, local or exotic, were displayed as a statement of their wealth, status and intellect. Just beyond the museums entrance theres a reconstruction of a typical dimly lit parlour, the showcase of the Victorian home. Amid the shadows, the iridescent wings of tropical birds glimmer within glass domes and metallic blue butterflies lie meticulously ordered in serried ranks in the drawers of polished mahogany cabinets. Collecting turned into an obsession for certain men with the time, money and means: country clergy, colonels recently retired from the Empires front lines or, in the case of Edward Booth, those who had inherited a substantial family fortune. When Booths expanding bird collection threatened to engulf the family home, he built this museum to house his overflowing hobby. Yet, while other Victorian museums crammed their cabinets with regimented rows of birds in strict scientific order, Booth was a pioneer in presenting his specimens posed within three-dimensional replicas of their natural habitats: dioramas. A yellowhammer broadcasts a silent song from a facsimile of a farmyard fence. Guillemots and razorbills jostle on sculpted sea cliffs. Two swooping skylarks defend their nest from a predatory stoat. Inside each diorama a different species is immortalised in a frozen moment, a recreation of the life that Booth had taken away. Upon his own death in 1890, Booth bequeathed his museum to the people of Brighton.