Pagebreaks of the print version

Extinct Languages

Johannes Friedrich

Introduction

In the history of human knowledge, the transition from the 18th century A.D. to the 19th is of no less a significance than is the turn of the 15th century A.D. into the 16th, which is regarded traditionally as the change-over from the Middle Ages to the Modern Era. Whereas about 1500 A.D. the discoveries and the Renaissance were reshaping the knowledge and mental attitude of mankind, the era about 1800 A.D. quite apart from the then nascent radical shift in political thoughtis characterized by a whole series of new and radical facts of knowledge, notably in the fields of the physical sciences and technology, and in connection with the latter in the technique of communications as well, which would justify the contention that in those fields the Modern Age began about 1800 A.D. This change in the natural sciences went hand in hand with a parallel change-over in various humanistic sciences. That was, for instance, the time when archaeology was given its new look, by Winckelmann, by the re-intensified study of original inscriptions, etc., and when the first steps were taken toward a true science of linguistics by the recognition of an Indo-European linguistic community, by a study of Germanic antiquity and by a systematic investigation and classification of all the recognizable languages of the world.

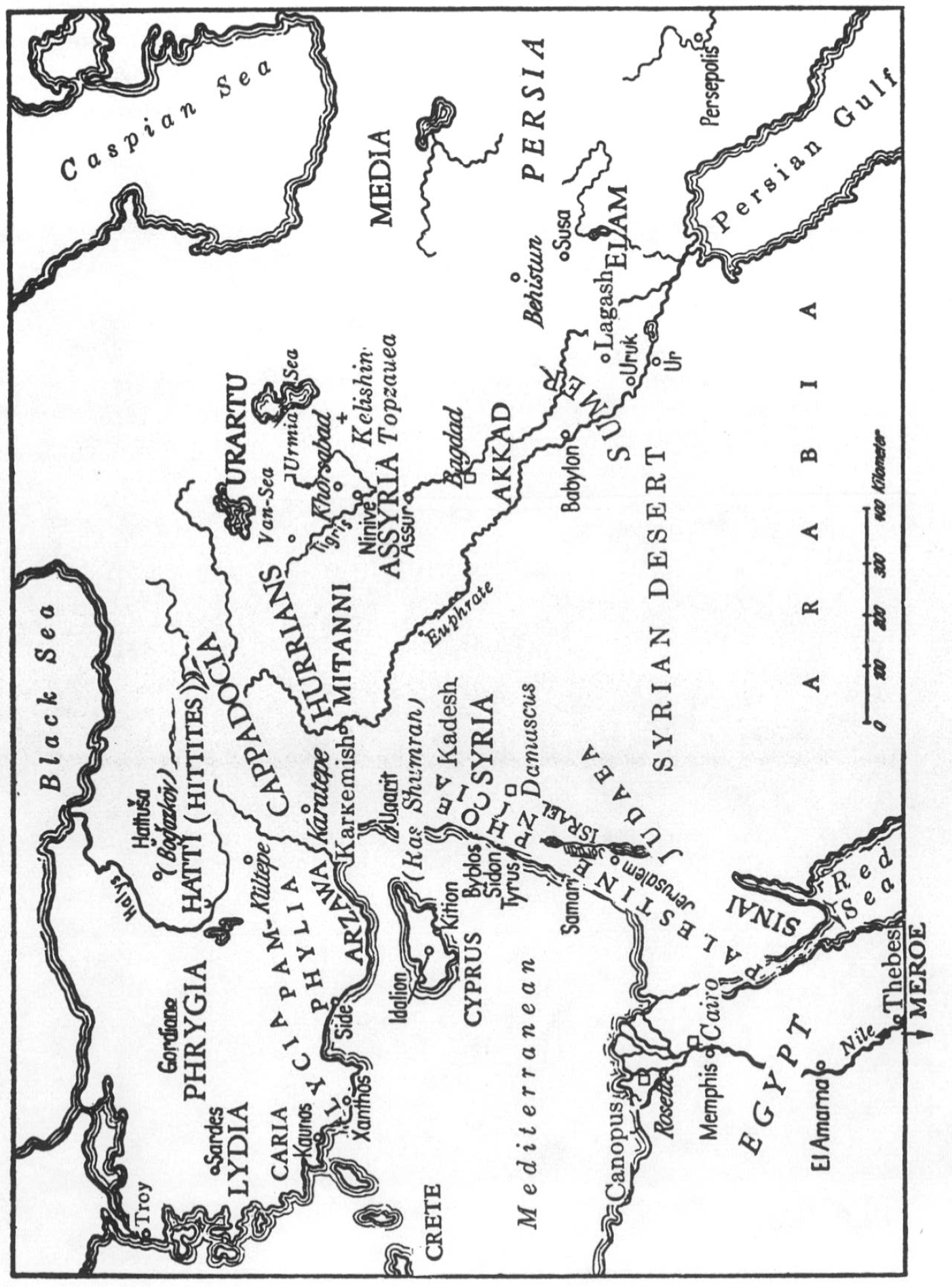

Another thing that happened about the same time was and this brings me right to the topic of the present book that the human mind began for the first time to look back at the races which had existed before the beginnings of Greek history, at the races which had shaped the earliest history of mankind in the Orient before the Greeks, at their material and abstract thinking, and at the residues of that thinking preserved in the inscribed monuments which had survived from that remote period of antiquity to the modern age. To the mind of the man of the 18th century, history had still begun, as it had for the Christian Middle Ages, with Homer and the tales of the Old Testament, and his knowledge of ancient tongues was restricted mainly to Latin, Greek, and perhaps Hebrew. Although a certain formal familiarity with the Old Egyptian monuments at least had been salvaged from remote antiquity into the modern age, the people of the 17th and 18th centuries still gazed with the same wonderment as had the Greeks and Romans at the odd pictorial characters with which those monuments were covered all over. But it never occurred either to the people of late antiquity or to those of the early Middle Ages to attempt to read this pictographic writing and to understand its contents. The knowledge of that script had been completely lost ever since it had ceased to be used. On the other hand, by today we have renewed our acquaintance with the Egyptian hieroglyphics and language, as well as with the cuneiform characters, once used in the Near East for writing a number of languages, but vanished from use and from the knowledge of mankind even earlier than the Egyptian writing, and there are also other formerly forgotten scripts and languages with which we have become re-acquainted. The scientists who contributed to these re-discoveries thus restored to linguistic science the lost knowledge of a number of languages, some of them very ancient, and they laid the first foundation on which a historical study of writing at all became possible. But above all, they expanded the historical horizon significantly toward the past. Whereas the surveyable history of mankind had formerly comprised about two and a half millennia, it was now expanded to take in at least five thousand years. And not only do the political events of those long years unfold before our eyes, but so does also the material and intellectual culture of those ancient races; their homes, their garments, their ways of living, their religious, juristic and scientific thinking come to life anew and open for us an insight into the development of human life and thought from a perspective far wider in space and time.

The decipherment of these old scripts and languages in the 19th and 20th centuries ranks with the most outstanding achievements of the human mind, and the only reason why it does not stand in the limelight of public interest as a co-equal of the radical triumphs of physics and technology and their related sciences is that it cannot produce the same effect on practical daily life which those discoveries can. This inferior evaluation is also the reason why the unlocking of the secret of extinct languages and scripts is never described coherently, and it is therefore still hardly known at all to the general public. Yet, this subject is deserving of the most careful attention of the learned minds, and is absolutely worthy of a presentation per se . This is the aim of the present book. I hope to be able to group the abundant material to a certain degree so as to provide a clear and comprehensive view, by first discussing at greater length the outstanding, and to a certain extent classical, decipherments of relics of the ancient Orient, that of the Egyptian hieroglyphics, of the many branches of the cuneiform writing, and of the Hittite hieroglyphics which remained enigmatic for a long time, but are now laid open to study. Next, I shall discuss, more briefly and in a looser arrangement, a few other decipherments of interest, without any attempt at completeness. Only then will I consider it proper to set forth a few theoretical reflections relative to the decipherment of extinct scripts and languages, such as follow readily from the previously explained practice. And in conclusion, I shall append the presentation of a few still undeciphered scripts, and I shall attempt to answer the query as to why they still remain un-deciphered.

J. F.

I. The Three Great Decipherments in the Study of the Ancient Orient

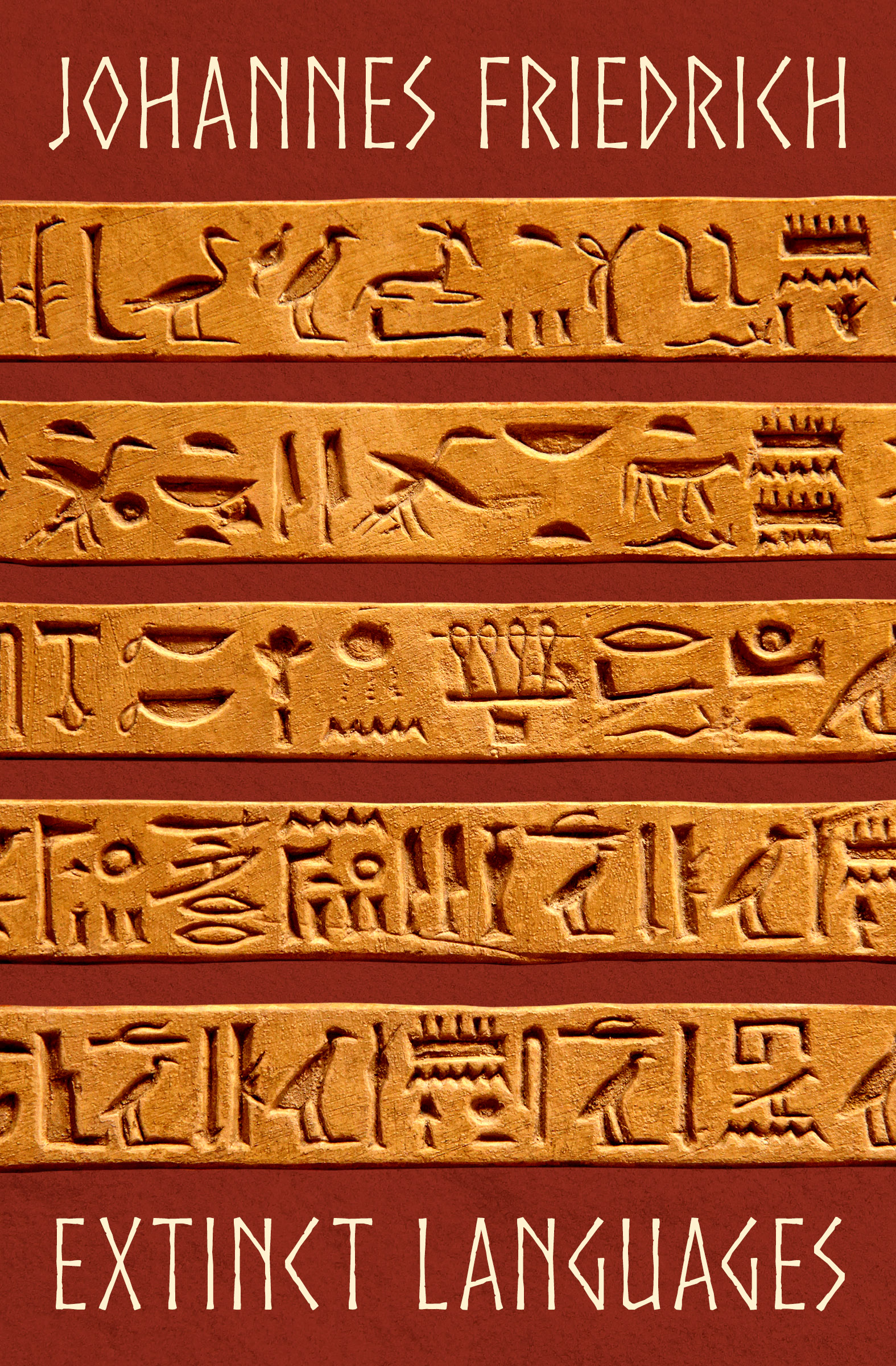

1. The Egyptian Hieroglyphics

Egypt is the homeland of the mysterious pictographic characters which even the ancient Greeks contemplated with reverent wonderment and called hieroglyphics, sacred signs, because they suspected that they contained secret wisdom of the magician priests of Egypt. With the obelisks in Rome also, this notion of a magic significance of the hieroglyphics survived among the beliefs of the Occident, and also profound minds of modern times permitted themselves to be influenced by it. Without a belief in a certain mysterious wisdom hidden within the hieroglyphics, a work of art like Mozarts Magic Flute would be inconceivable. This is why it is fitting that a presentation of the decipherments be introduced by a discussion of the Egyptian hieroglyphics. For the sake of clarity, also a brief geographic and historical survey will be useful.

(a) Land and People, History and Culture

The cultural situation on African soil is rather simple; in the ancient days there was only one known civilized race there, the Egyptians whose mighty edifices and the pictographic writing on them still fill the modern visitor with no less amazement than they inspired in the ancient Greeks.