Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

T his is a book about a period of time, not so long ago, when significant portions of the Earth were still cloaked in mystery. Long before the invention of the internet or cell phone technology, it was also an age when real-life heroes went about their work far from the glare of the twenty-four-hour news cycle, and were often cut off from the rest of the world for weeks, if not months, at a time.

The individuals who populate this story were a complicated lot. Some were principled, steadfast, and tenacious. Others were devious and cowardly. A handful were brilliant, others foolhardy. Like you, however, most of them were avid readers. On the highest mountains on the planet, where every additional ounce might determine the difference between victory and defeat, they brought along dog-eared copies of Wuthering Heights, Pride and Prejudice, and The Oxford Book of Greek Verse in their rucksacks. Two thousand feet below the summit of Mount Everest, inside a tiny tent pitched along a murderous ridge, a British climber named Eric Shipton tried to read, by flickering candlelight, Thorton Wilders The Bridge of San Luis Rey , a novel which questioned the meaning of life in the face of the sudden and deadly collapse of an ancient rope bridge in eighteenth century Peru.

Many people believed that mountain climbers, as a whole, were mad.

Some undoubtedly were.

One dark, drizzly evening, while I was doing research for this book, I found myself walking along the back streets of Darjeeling, a mystical hill town perched along the edge of the eastern Himalayas. With the help of a local guide, I was trying to locate the former home of a legendary Sherpa, named Angtsering, who had worked on mountaineering expeditions back in the 1930s. While the old man was deceased, I had heard that his daughters still had a box of his climbing paraphernalia. Such materials, Id reasoned, might help me to tell the story of the forgotten men and women who, decades earlier, had set out to climb the highest and deadliest mountains on Earth.

Finally, the guide and I found the house, a low-slung affair, painted a bright aqua with red gutters and windows trimmed in white. His elderly daughters met us at the door, dressed in long, coatlike sweaters and floor-length, patterned dresses. Clearly nervous, and uncertain of exactly what we wanted, they nevertheless invited us in and out of the rain. But as soon as the conversation turned to their father, their eyes brightened, cups of hot tea suddenly materialized, and from a battered wooden box came out old photographs and copper medals and newspaper clippings yellowed with time. Sitting in the sisters snug living room, for a couple of brief, magical hours we were transported to another age, a time when awe and wonder lived on mountaintops, and the world was still fresh and new. I hope you will find some of that in these pages as well.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

D uring the darkening decade of the 1930s, as the winds of war began to gather in the chanceries and defense ministries of central Europe and the Far East, and dictators began to trace lines on maps with their fingers, there was a race like no other. It had no fixed starting point, no single finish line, no referees, and no written rules. And while it would ultimately involve men and women from ten nations, capture front-page headlines around the globe, and claim dozens of lives, its most remarkable feature was that this was a race to a place that no human being had ever been before.

In truth, there werent many such places left.

For the world had already grown perilously small. The North and South Poles had already been conquered. Explorers and scientists, armed with quinine, Colt .32-caliber automatic pistols, and gabardine jackets from Abercrombie & Fitch, had hacked their way into the highlands of New Guinea, uncovered a lost city in Peru, and gazed with awe and wonder upon Alaskas Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. A Frenchman had driven a modified Citren automobile two thousand miles across the Sahara Desert, while a sixteen-year-old ranch hand in New Mexico, mistaking a plume of bats for a funnel of smoke, discovered the most magnificent cave system on Earth.

Even former President Teddy Roosevelt, overweight and nursing an infected leg, had, in 1913 and 1914, ridden a dugout canoe hundreds of miles down the piranha-infested Rio da Dvidathe River of Doubtinto the far reaches of the Amazon basin. And one long day in June 1928, a former Kansas tomboy turned Cosmopolitan editor had flown in a Fokker Trimotor from Newfoundland to Wales, becoming the first woman to cross the Atlantic in an airplane. When she returned home to the United States, Amelia Earhart was given a ticker-tape parade on Broadway and a private audience with President Coolidge in the White House. Even the remotest island in the vast Pacific Ocean had, at one time or another, felt the scrape of a boat keel against its shoreline. There was no place on earth, it seemed, that was beyond the reach of humankind.

Except for one.

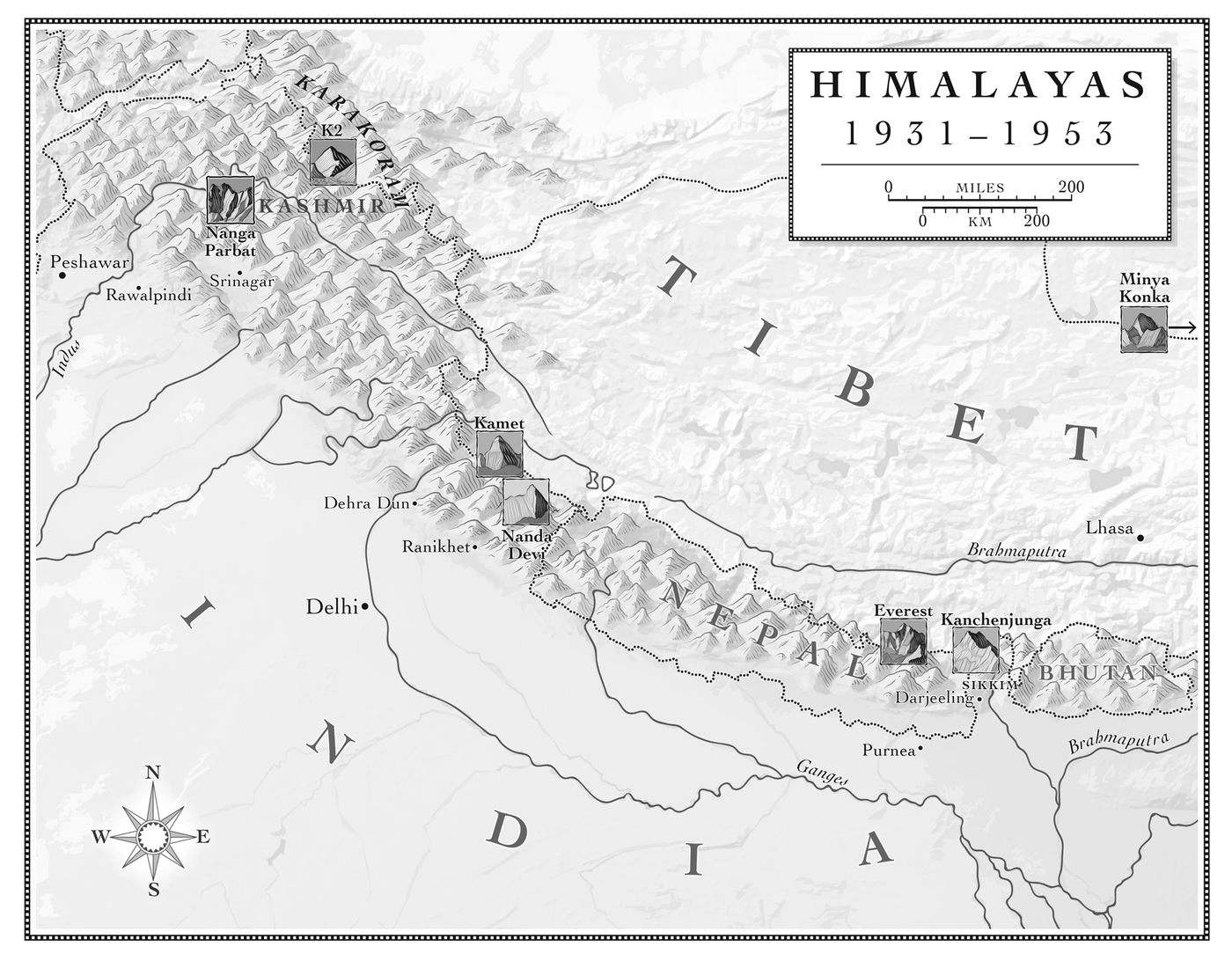

Stretching for more than two thousand miles from the Hindu Kush of eastern Afghanistan to the far reaches of western China, the Himalayas are the tallest and mightiest mountain range on the planet. But the tops of its highest peaks, some fourteen in number, all of which stand more than eight thousand meters, or 26,246 feet, high, had never felt the weight of a human being. Mount Everest, of course, was the best known, but the others, like K2, Annapurna, and Kangchenjunga, were equally majestic and foreboding. The southern face of Nanga Parbat, along the edge of Kashmir, shot up nearly ten thousand vertical feetroughly the height of ten Empire State Buildings stacked end to end. Twice as high as the Alps or the Rockies, these were true geographical monsters, behemoths of rock and ice so large that they created their own weather systems.