Athens at the Margins

hens at the Margins

Pottery and People in the Early Mediterranean World

Nathan T. Arrington

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-175201

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-222660

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Rob Tempio and Matt Rohal

Production Editorial: Brigitte Pelner

Jacket/Cover Design: Pamela L. Schnitter

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Alyssa Sanford (US) and Charlotte Coyne (UK)

Copyeditor: Dawn Hall

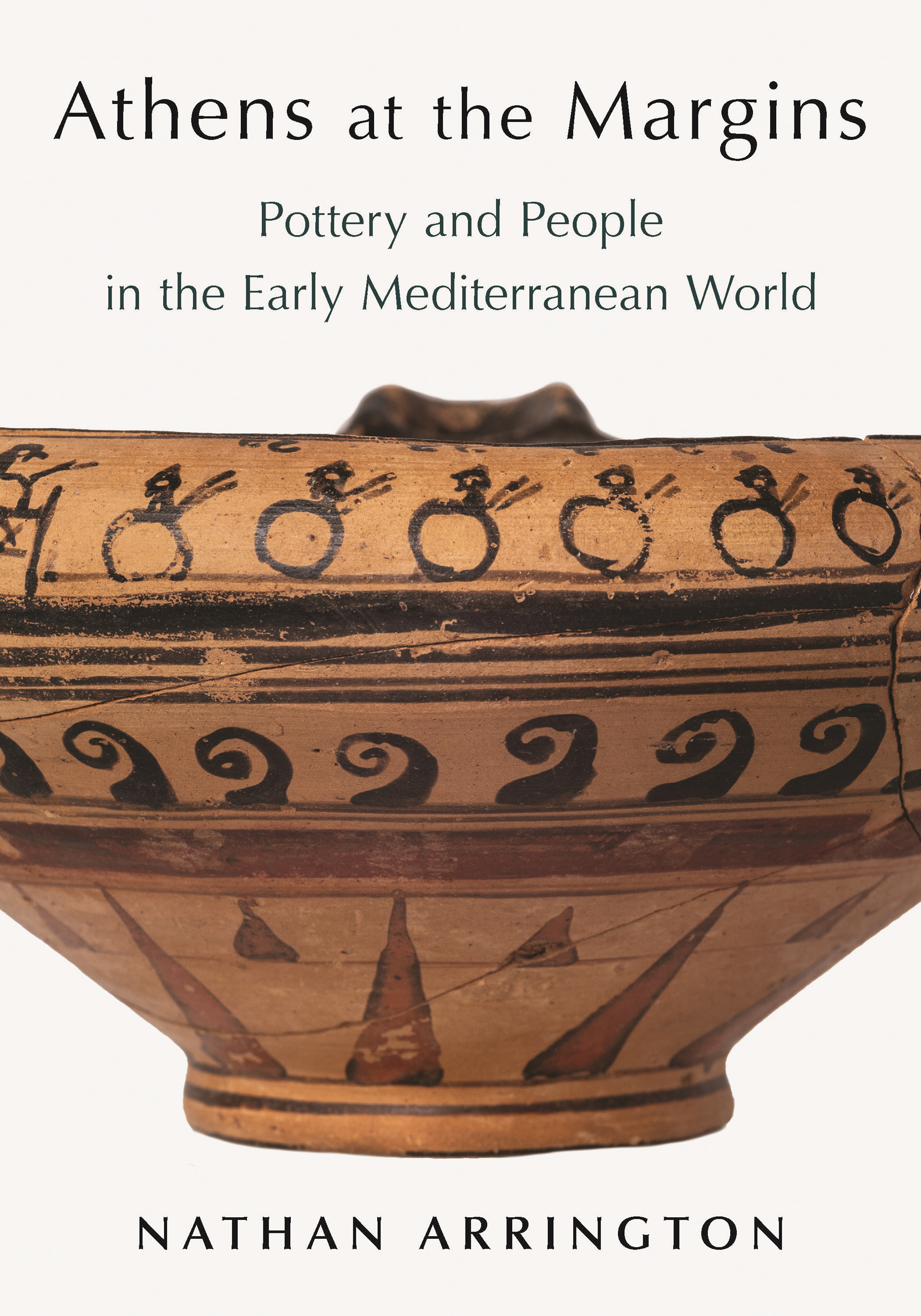

Jacket Image: Late Protoattic louterion from Palaia Kokkinia (northern Piraeus) ca. 630620 BC. Photo: Jeff Vanderpool

This publication is made possible in part by the Barr Ferree Foundation Fund for Publications, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University

FOR CELESTE

Contents

- ix

Preface and Acknowledgments

After graduating from the university, I had the good fortune to work at the Princeton University Art Museum, and I vividly remember one day in the storage rooms holding a Near Eastern cylinder seal, turning it over and over again in my hand, wondering what Greeks might have thought of it. I pursued some form of this question in two masters theses on glyptics over the next few years at Cambridge and Berkeley, until an advisor warned (perhaps mistakenly) that there were no jobs in gems. But the bigger issue of the connections between Greece and the Near East continued to tug at me. As I started to work on the problem anew, I became increasingly frustrated with the elite-dominated narratives. Not only were these one-sided from a social point of view, but they also neglected the types of finds that I encountered on excavations, when I sorted through mundane albeit very old trash in the expectation that it could tell us something significant about the ancient world and the people who lived there. There was a tension between the types of objects that archaeologists thought could inform the writing of history and the types of objects that were used to understand Orientalizing. So I set out to write a book about GreekNear East relations and the role of the nonelite in cultural changeonly to discover that it was not possible, or at least, not in the way I had first imagined it. Framing the question in terms of GreekNear East relations entailed accepting a host of assumptions about geography, chronology, and cultures that proved problematic. The regional variation in the period was so pronounced that writing about Greece in the seventh century seemed as misleading as writing about an Orient. I started to realize how limited, constrained, even chained I was by periodization and the acquiescence it demanded. It took me longer than I care to admit to recognize that I would need to narrow my focusto ceramics and to Atticain order to attempt to tackle the larger issues, and that I needed historiography to get out of the morass. Historiography took me to Phaleron and to the nomenclature Phaleron Ware, which once was used to describe seventh-century pottery but has been expunged from the scholarly vocabulary. As I was working on this book, excavations began anew in Phaleron, yielding sensational finds, including mass burials with bodies that seem to have suffered some form of capital punishment. Phaleron was suddenly back in the picture, but archaeologists and historians didnt seem to know where to place it. I hope this book can move that cemetery, the people buried in it, and others like them from the margins closer to the center of our attention.

In developing this project, I have benefited enormously from the generosity of the following colleagues who contributed their time and expertise to read parts of this manuscript: Anna Alexandropoulou, Seth Estrin, Nota Kourou, Jessica Lamont, Suzanne Marchand, J. Michael Padgett, Catherine Pratt, Avary Taylor, Marek Wcowski, and the Presss two anonymous readers. They have made this a better manuscript but are not to blame for my interpretations or my mistakes. I also would like to acknowledge the valuable input that I received from the following scholars: Marian Feldman, Tonio Hlscher, Carl Knappett, Antonis Kotsonas, Sarah Morris, Angelos Chaniotis, Stella Chryssoulaki, the members of Comparative Antiquity (organized at Princeton by Andrew Feldherr and Martin Kern), and the participants in New Antiquity (convened at Stanford by Jennifer Trimble and at Kings College by Michael Squire). I appreciated the opportunity to talk about my work and to learn from audiences at Brown University, the Johns Hopkins University, the Institute of Fine Arts, the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, the University of Oxford / Ashmolean Museum, and the University of Toronto / Royal Ontario Museum. Members of two graduate seminars on The Orientalizing Phenomenon offered trenchant readings of secondary scholarship and fresh, insightful ideas.

I owe the greatest debt of gratitude to my wife, Celeste, and to our two daughters. Even in the darkest moments of spring 2020, we found joy together.

Princeton, New Jersey

August 2020

Athens at the Margins

CHAPTER 1

The Margins

This book recovers a style of painting that does not fit neatly into our histories of Greek art but that can offer new perspectives on Athens, its place in the Mediterranean, and the people who lived there. The style has been called crude, awkward, and, on occasion, just ugly ( Perhaps nothing so clearly indicates the challenge in making the style conform as the prevalent label still used in textbooks to categorize and describe much of the seventh-century style made in Attica, and elsewhere in Greece: Orientalizing. It is just not Greek enough.

The beguiling aesthetics of a regional style whose middle phase is classified simply as the Wild Style compels us to look again. And some of the very same authors who critique the style as ungainly also recognize in it something unusual, remarkable, and noteworthy. This is a period, and a phenomenon, that merits scrutiny. And we must look at this pottery again, and more closely, if we want to understand some of the major developments in Greek culture that took place at the same time as these vases were made and used. Since very few written sources survive, pottery is the best body of evidence for broader investigations of society at a time when the city-state or polis developed, new interpersonal relationships formed, and Greek communities engaged with Mediterranean connectivity. But it is a complicated source of evidence, which has been used for social analysis primarily through recourse to the problematic concept of Orientalizing and structuralist models emphasizing elite agency. In this book, I work to loosen Protoattic from an Orientalizing paradigm and to recover the importance of the margins and the marginalized. To do so, the book moves from historiography through a variety of contextsthe cemetery, the workshop, the symposium, and the sanctuarybringing the historical, geographic, and social margins into sharper focus and looking at how art and people interacted in the construction of subjectivities and communities.