A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF HAIR

VOLUME 6

A Cultural History of Hair

General Editor: Geraldine Biddle-Perry

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Hair in Antiquity

Edited by Mary Harlow

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Hair in the Middle Ages

Edited by Roberta Milliken

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Hair in the Renaissance

Edited by Edith Snook

Volume 4

A Cultural History of Hair in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Margaret K. Powell and Joseph Roach

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Hair in the Age of Empire

Edited by Sarah Heaton

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Hair in the Modern Age

Edited by Geraldine Biddle-Perry

A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF HAIR

IN THE

MODERN AGE

VOLUME 6

Edited by

Geraldine Biddle-Perry

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO PART I

CHAPTER TWO PART II

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

A Cultural History of Hair offers an unparalleled examination of the most malleable part of the human body. This fascinating set explores hairs intrinsic relationship to the construction and organization of diverse social bodies and strategies of identification throughout history. The six illustrated volumes, edited by leading specialists in the field, evidence the significance of human hair on the head and face and its styling, dressing, and management across the following historical periods: antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, the Age of Empire, and the Modern Age.

Using an innovative range of historical and theoretical sources, each volume is organized around the same key themes: religion and ritualized belief, self and societal identification, fashion and adornment, production and practice, health and hygiene, gender and sexuality, race and ethnicity, class and social status, representation. The aim is to offer readers a comprehensive account of human hair-related beliefs and practices in any given period and through time. It is not an encyclopedia. A Cultural History of Hair is an interdisciplinary collection of complex ideas and debates brought together in the work of an international range of scholars.

Geraldine Biddle-Perry

GERALDINE BIDDLE-PERRY

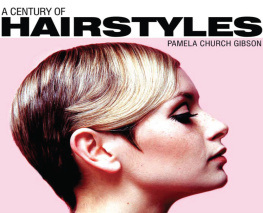

Consider an image of a postiche simply titled Modern Hairstyle from 1956 (). The hair is cut short over the ears and into the nape of the neck; it is uniformly colored, and artfully coiffed high off the forehead to form a wreath of curls that frame the angular planes of the mannequins face. This is the conceptual starting point of this collection of chapters: how does a hairstyle come to be seen as representative of what it is to be and to look modern at a particular moment in time.

The ability to adapt the body to shifting conceptions of the self and the experience of living in a particular age, here the modern age, renders the hair on our head a dynamic site of interpretation, for individuals and social groups engaged in the day-to-day rituals of body management, for writers, artists, scientists, designers, hair practitioners, photographers, film-makers, commercial enterprise, actors and performers, and of course for historians and theorists. It is this complex interaction between what hair is, what canand cannotbe done with it (theoretically, aesthetically, culturally, fashionably), and what it means to different people in different contexts, that the chapters in this volume grapple with. The task in its infinite discursive dimensions is comparable to that of its subject matter. No one historical example can be reduced to a single meaning nor stand for all, nor can every potential variation in practice or interpretation be addressed. Any examples chosen also bring their own historiographical problems. Hairstyles are frequently trapped and trivialized in a version of fashionable clothings reductive hemline history that merely documents the longs and shorts of style trends in clothes and head and facial hair as synonymous with particular epochs. Clearly, a century of change is more complex than a series of hairstyles. Nevertheless, the trends and the mechanisms of popular memory that iconize them are also embodied in social practices that acquire meanings, or to which meanings are attached, through rituals, ideologies, technologies, and beliefs that are relevant to the construction of modern sensibilities and, thus, to an understanding of the modern age itself.

The chapters that follow attempt to overcome or at least negotiate these complexities through a flexible schema of interpretation: key themessocial organization, fashion, race, gender, religion, class, sexuality, hygiene, representationseparately structure each chapter, but these constantly overlap and frequently collide in the analyses of definitively modern hair styling innovationsthe bob, the perm, the blonde, the Afrothat to a greater or lesser degree inform all of the chapters. The intention is to critically explore hairstyles in a way that allows them to be conceptually and theoretically expanded and developed in an unfolding mix of contextual and thematic alternatives. Chapter by chapter, the interaction of these two impulses, the thematic and the topical, aim to enrich an understanding and the critical potential of a vital cultural form still overlooked in many contemporary histories of the body.

By way of example, each cultural milieu and social context poses different questions for each of the chapters but it is impossible to understand the modern age without addressing in some way the huge impact the bobbing, that is, cutting short, of womens hair had on every aspect of culture in the interwar period. For some chapters, the style is situated as the symbol of both change and the experience of change expressed through the body, and operates as a catalyst for the arguments that follow. Royce Mahawatte (in fashioning of new kinds of social bodies? How are these embodied in everyday regimes of hair styling and management practiced in new kinds of places and spaces, in modernist literature and Hollywood cinema, in advertising and popular culture, childrens toys, and in the hashtag# communities of the twenty-first century?

Alice Beards chapter (, Fashion and Adornment) then develops this line of argument. However, the focus here is on the allure and status the latest styles brought to young women and how such concepts were incorporated into a rhetorical narrative of new attitudes to gender and sex roles in a burgeoning film industry, and in all kinds of visual and material culture more broadly. The modern salon, the cinema screen and fashion page, and the contemporary catwalk, Beard argues, offer spectacular forums for the creation and consumption of the look, a fusion of fashionable clothes and hairstyles that functioned at an ideological level as the symbol of the gender politics of modern femininity in the twentieth century and beyond.

Beard and Mahawatte in their different ways examine how the bob in the 1920s transgressed traditional gender body codes at a time when patriarchal authority and an old social order were seen as under threat, and the tangible historical barriers to fashionable consumerism were beginning to if not disappear then certainly dilute. The figure of the flapperimmediately recognizable by her bobbed hair, androgynous silhouette, and morally and physically fast lifestylesignaled youth and new attitudes to the body, particularly the sexual body. At the same time, womens hair was invested with an exaggerated eroticism in sensational accounts of its barbering in the popular press, and in the expanding spectacle of moving pictures aimed at a largely female audience. Beard explores how on and off screen the early stars of the silent era such as Colleen Moore and Louise Brooks offered a spectacular version of a visibly constructed modern femininity endlessly replicated in an expanding popular media and progressively, in salons in every suburban high street and parade. The simply cut bob and the flapper rage were in fact short-lived trends, but the look became synonymous with a desire for, if not the realization of, wider political and social change. This is significant Beard argues, in that such desires were now perceived as being fulfilled in autonomous acts of modern consumerism that did not just embody radical change but engendered it.

Next page