2010 by David E. Stuart

All rights reserved.

Published 2010 in the United States of America

16 15 14 13 12 2 3 4 5 6

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Stuart, David E.

Pueblo peoples on the Pajarito Plateau: archaeology and efficiency / David E. Stuart.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8263-4911-8 (paper: alk. paper)

ISBN EPUB: 978-0-8263-4912-5

1. Pueblo IndiansNew MexicoPajarito PlateauAntiquities.

2. Pueblo IndiansNew MexicoBandelier National MonumentAntiquities.

3. Social archaeologyNew MexicoPajarito Plateau.

4. Social archaeologyNew MexicoBandelier National Monument.

5. Survival skillsNew MexicoPajarito PlateauHistoryTo 1500.

6. Survival skillsNew MexicoBandelier National Monument History To 1500.

7. Pueblo IndiansNew MexicoPajarito PlateauSocial life and customs.

8. Pueblo IndiansNew MexicoBandelier National Monument Social life and customs.

9. Pajarito Plateau (N.M.)Antiquities. 10. Bandelier National Monument (N.M.)Antiquities.

I. Title.

E99.P9S86 2010

978.9004'974dc22

2010027469

IN MEMORY OF

Frederick A. Peterson

19192009

Field director of the great Tehuacan Valley Project, friend, mentor, and author of Ancient Mexico

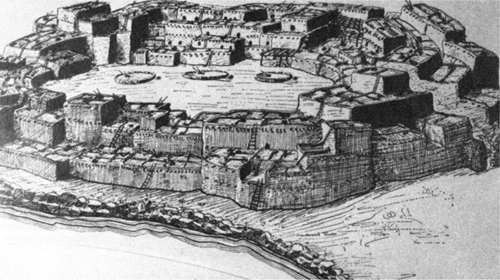

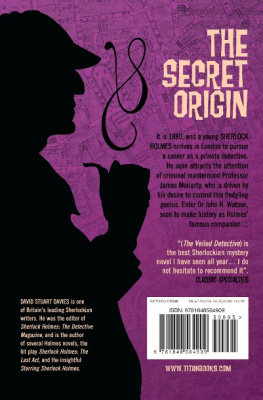

Artists conception of the pueblo called Tyuonyi at Bandelier National Monument. This rendition makes the building look more massive than it probably was. Courtesy National Park Service, Bandelier National Monument.

Preface

Since my book The Magic of Bandelier was published in 1989, the raw archaeological data available from New Mexicos Bandelier National Monument have tripled. Archaeologists such as Robert Powers, Janet Orcutt, Timothy Kohler, and Rory Gauthier are to thank for this bounty. Because of their work, this book is not just a freshening up of the earlier one. It is so heavily rewritten, added to, and refocused that it isnt the same book at all.

I wrote The Magic of Bandelier as a guidebook for visitors at a time when far fewer guidebooks existed than is now the case (although Dorothy Hoards several editions remain mandatory reading). In 2005, the School for Advanced Research Press in Santa Fe, New Mexico, published The Peopling of Bandelier, edited by Robert Powers, which filled the need for a book painting a much larger picture of Bandelier than those available in marker-by-marker trail guides. That well-written, beautifully illustrated, and information-rich book offers readers a wide-angle view of anthropological archaeology at work.

I have a more precise goal for Pueblo Peoples on the Pajarito Plateau. Here I concentrate on settlement and subsistence data in order to show how Bandelier Monument and the plateau on which it sits became the Southwests most densely populated area after the powerful society centered in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, collapsed in the 1100s CE (common era). Until then only lightly inhabited by foraging and hunting folk, the Pajarito Plateau had remained probably the northern Southwests most important upland ecological preserve. Migrating to it gave some of the stunned survivors of Chacos fall a place in which to refashion themselves and rise from catastrophe. This re-formation of ancestral Pueblo society required people to rebalance the Chacoans final obsession with growth, grandeur, and hierarchy with a return to a way of life of much greater efficiency, moderation, and practicality. These qualities were key to their survival.

In another earlier book, Anasazi America (2000), I wrote about forces I refer to as power and efficiency in human social evolution. Briefly, power is most valuable for pushing growth and managing hostile competitors as a society enlarges. Its most notable archaeological signature is huge structures and a costly, expanding infrastructure. Efficiency reigns in times of want or scarcity, so its archaeological signature is a modest, practical infrastructure, fewer lavish structures, and tools and other goods that are used, repaired, and reused. Getting the balance between power and efficiency right for the technology and resources available at a given time is the most critical issue a society faces. Fantasy and wishful thinking do not suffice.

The story I tell about Bandelier and the northern Rio Grande region differs a bit from that offered by Powers and his coauthors in The Peopling of Bandelier and from the view put forward by Timothy Kohler in his book Archaeology of Bandelier National Monument (2004). They argued that Bandelier began to fill up with people about 1150, and thereafter population shifted into higher elevations. I believe that a few farming-focused early-comers began to filter into the northern Rio Grande as early as the 1000s, digging pithouses and founding small pueblos. A peak of pithouse construction at higher elevations to the north of Bandelier can be dated to 1153 on the basis of patterns across 200,000 square miles of the greater Southwest. Just why similar pithouses have not been found in the monument itself is a significant question. Was the Pajarito still inhabited by Archaic-style forager-hunters long after they disappeared from the Four Corners country? Or was most of the southern Pajarito a hunting preserve so valuable to surrounding, long-established, upland pithouse dwellers that few actually lived in it? Examples of such hunting grounds are certainly known for many historic tribal societies.

I deviate again from earlier writers formulations of the years from 1290 to 1325 by arguing that because of drought, the main body of the upland populations moved eastwarddownhill and downstreaminto the Rio Grande Valley at that time. Some villagers then revisited their briefly abandoned upland holdings as early as the 1320s to 1340s, using the higher elevations as a safety valve during dry periods when farming in the valley bottom became too unreliable.

These departures arise from the fact that I am a student not of pottery or architectural form but of evolutionary and ecological dynamics as evidenced in broad settlement patterns and peoples uses of different niches in the landscape. Thus, I see the beginning and the first, temporary, ending of the Pajaritos so-called Coalition periodthe years between about 1290 and 1325as dynamically critical to understanding the re-formation of Puebloan society, a renewal that allowed it to survive for another eight hundred years.

This volume indulges my passion for guiding readers toward an understanding of just how Bandelier National Monument and the Pajarito Plateau fit into an epic Southwestern story, now six hundred human generations long. Although I focus on the archaeology of the monument and the plateau, much of what archaeologists know about them depends on events that happened to ancient people far away and centuries before the sites preserved in the monument were built. Learning about this context is the best way to make good sense of the archaeological remains found on the plateau.