The City in the 21st Century

Eugenie L. Birch and Susan M. Wachter, Series Editors

A complete list of books in the series is available

from the publisher.

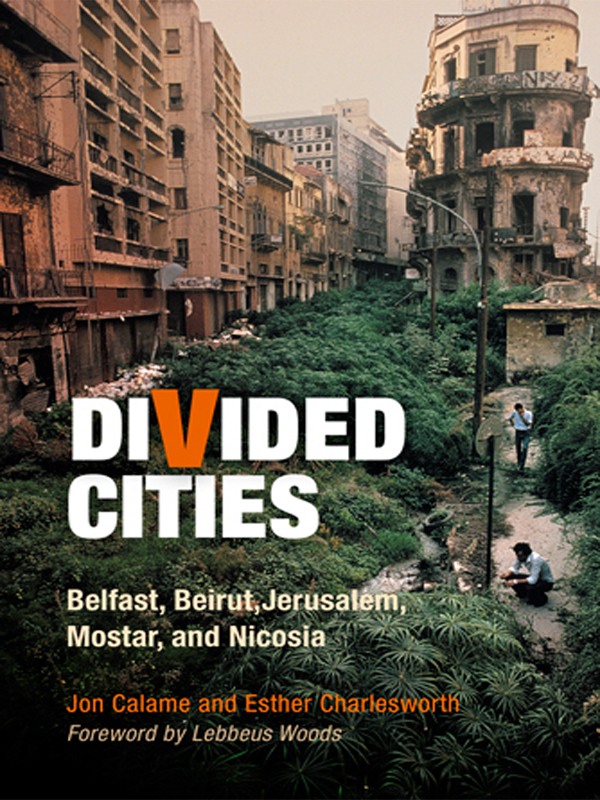

Divided Cities

Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem,

Mostar, and Nicosia

Jon Calame and Esther Charlesworth

PENN

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia

Copyright 2009 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Calame, Jon.

Divided cities : Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Mostar, and Nicosia / Jon Calame and Esther Charlesworth.

p. cm.(The City in the 21st Century)

ISBN: 978-0-8122-4134-1 (alk. paper)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. City and town life. 2. Urban violence. 3. Urban warfare. 4. Persecution. 5. Population transfers. 6. Beirut (Lebanon)History. 7. Belfast (Northern Ireland)History. 8. JerusalemHistory. 9. Mostar (Bosnia and Hercegovina)History. 10. Nicosia (Cyprus)History. I. Title. II. Charlesworth, Esther Ruth

HT153.C24 2009

307.76dc22

2008035354

Foreword

Lebbeus Woods

The five cities under study in this book are vitally important to an understanding of the contemporary world. Each is different, in that each emerges from a unique historical background, belonging to a quite particular and localized set of cultural conditions. Yet, each shares with the others a common set of existential factors, belonging to what we might call an emerging global condition. Prominent among these is sectarianisma confrontation of differing, though not necessarily opposed, religious beliefs, leading to widespread violenceand a stopgap solution focused on the physical separation of conflicting parties and communities. The other feature shared by the cities under study is that the stopgap solution of separation, intended as an emergency measure to prevent bloodshed and disorder, turns into more or less persistent, if not permanent, division. No one intends to create divided cities as a long-term solution to sectarian violence; rather, such cities emerge from the seeming intractability of the conflicts and their causes.

The story of the present is increasingly being written in terms of religious conflicts. The secularism of the West is exposed through globalization to the sectarian quarrels that bedevil many regions of the world. Western institutions of government and commerce, which operate according to democratic processes or market-savvy principles, are no match in single-minded determination for those elsewhere driven by religious fervor. On the defensive, they have hardened their own positions accordingly. At the same time, Western politicians are not above exploiting religious differences to disguise neocolonial ambitions.

Going against two centuries of growing liberalism in the West, there are many new wallsphysical, legal, psychologicalbeing hastily thrown up in the interests of security to separate us from them. This goes beyond realities of gated communities for the rich, and restrictive, ethnically biased immigration laws, extending to attempts to seal entire national borders. If the perceived threat of religious warfare increases dramatically, it is conceivable that, not only in the West, ghettoes and internment camps may be deemed necessary. Looking to the future, this is the worst-case scenario. Can things possibly get that bad, in this information-enlightened age?

To insure they will not, it is necessary to understand not only the tragic mistakes of the past, but also the dynamics of the present in terms of the polarization of peoples and their communities. Critical aspects of these dynamics are revealed in this book, for in the physical divisions of Beirut, Nicosia, Belfast, Mostar, and Jerusalem the means by which fear and misunderstanding are given physical form are revealed in all their dimensions. Once in place, the barriers separating disputing groups become the mechanisms for sustaining the urban pathology of communities at war with themselves. The right thing, as this book inspires us to imagine, is to remove the barriers and replace them with new openings for dialogue and exchange. The best thing, however, is never to build the barriers at all. It is to that distant, but attainable, goal that I believe this book is dedicated.

Preface

This book is the result of research conducted between 1998 and 2003 in five ethnically partitioned cities: Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Nicosia, and Mostar. As it went to press in 2008, Beirut still smoldered in the wake of new clashes between Hezbollah and Israel, Baghdad neighborhoods were partitioned according to religious sect, and racial divisions in New Orleans following the Katrina hurricane were still starkly unmended. Though old divisions persist and new ones emerge, fresh insights about how and why urban partitions happen remain in short supply.

The effort to isolate patterns that could provide such insights began in 1996 with our involvement in a reconstruction planning workshop in the Bosnian city of Mostar. The capacity of the divided administration there to coordinate an effective response to social and physical crises in the postwar context was severely limited. Many capable foreign experts stayed away, too, emphasizing the need for a political settlement before revitalization could progress. Investment prior to unification would effectively sanction ethnic segregation, they argued. Still, foreign professionals of all types poured into this vacuum to provide humanitarian assistance, funding, and advice of all kinds.

We were among the dozens of foreign architects, planners, and conservators who visited Mostar with the intention to work despite the political stalemate. We saw that important decisions regarding reconstruction were being left to self-anointed foreign donor agencies working, for the most part, in an isolated and unregulated fashion. It was clear that preliminary consideration of long-term impacts, tradeoffs, and models for successful post-conflict development was rare. Even if those involved had wanted to plot their moves more systematically, the kind of documentation and analysis needed to support such considerations simply did not exist.

A credible response to the questions we encountered in Mostar required close examination of other cities polarized by ethnic conflict. This book summarizes the patterns and insights that emerged in relation to pre- and post-partition phases of urban development. We conclude that divided cities are not aberrations. Instead, they are the unlucky vanguard of a large and growing class of cities. In these troubled places, intercommunal rivalry seems inevitably to recommend physical segregation.

Our discussions with urban professionals, politicians, policymakers, cultural critics, and residents in these five cities suggest that mistakes could have been avoided if decision makers had possessed a broader understanding of urban partition's causes and consequences. We learned that symptoms of discord in the urban environmentin particular, physical partitionsoften affirm local assumptions about persecution and encourage one ethnic community to antagonize another. In this sense, they are a self-fulfilling prophecy of involuntary separation and militancy between urban neighbors with a history of mutual distrust.