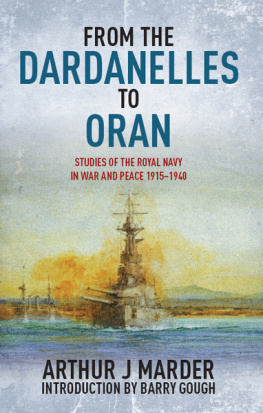

ARTHUR J MARDER was a meticulous researcher, teacher and writer who, born in 1910, was to become perhaps the most distinguished historian of the modern Royal Navy. He held a number of teaching posts in American universities and was to receive countless honours, as well as publish some fifteen major works on British naval history. He died in 1980.

BARRY GOUGH, the distinguished Canadian maritime and naval historian, is the author of Historical Dreadnoughts: Arthur Marder, Stephen Roskill and the Battles for Naval History, and contributed new introductions to Marders five-volume history of the Royal Navy in the First World War From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow and From the Dardanelles to Oran, all recently published by Seaforth Publishing.

Churchill with General Irwin, G.O.C. 11 Corps, on his left, and General Sir Ronald Adam, G.O.C. in C. Northern Command (far right) in East Anglia just before operation Menace in 1940

Copyright Arthur J Marder 1976

Introduction copyright Barry Gough 2016

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

Published and distributed in the

United States of America and Canada by the

Naval Institute Press,

291 Wood Road, Annapolis,

Maryland 21402-5034

www.nip.org

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934373

(UK) ISBN 978 1 84832 390 2

(US) ISBN 978 1 59114 725 1

PDF ISBN: 978 1 84832 393 3

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 84832 392 6

PRC ISBN: 978 1 84832 391 9

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Introduction

T HE GERMAN INVASION of France, the collapse of French military power, and the acceptance by France of an armistice with Germany and Italy indicated a great shift in the geopolitics of the Second World War in Europe. Hitherto an ally of Britain, the government of Bordeaux and then Vichy surrendered all autonomous action, and in so doing abandoned all formal allied connections with Britain. Although promise of a united government had been offered by the United Kingdom, this was set aside by the rapid turn of events.

On 4 July 1940 Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister, announced to the House of Commons measures taken to prevent the French Fleet from falling into German hands. The Bordeaux government had been given a chance to save the Fleet, and to allow it to sail unhindered to various British ports. Naval emissaries had with painful necessity appealed to French admirals to allow the ships to pass to the Royal Navy and had failed in their task. London decided to destroy French naval units. At the time, and later in hindsight, British admirals Cunningham, Somerville and North thought that Londons forceful policy of bringing the matter to a crisis by attacking French warships at the naval port of Oran, Mers-el-Kbir, was wrong. Churchill disagreed with the admirals: the capital ships of the French navy would have been placed within the power of Nazi Germany under the Armistice terms signed in the railway coach at Compiegne. The transference of these ships to Hitler would have endangered the security of Great Britain and the United States. We therefore had no choice but to act as we did, and to act forthwith. Our painful task is now complete. And so the deadly stroke was executed, and Churchill never shied away from his responsibility in this. As General Wolfe remarked, war is an option of difficulties.

On 20 August 1940 Churchill outlined in review the situation presented as to the disposition of the French Fleet. Shielded by overwhelming sea power, possessed of invaluable strategic bases and adequate funds, France might have remained one of the great combatants in the struggle. Now all was changed.

That France alone should lie prostrate at this moment is the crime, not of a great and noble nation, but of what are called the men of Vichy. We have profound sympathy with the French people. Our old comradeship with France is not dead. In General de Gaulle and his gallant band, that comradeship takes an effective form. These free Frenchmen have been condemned to death by Vichy, but the day will come, as surely as the sun will rise tomorrow, when their names will be held in honour, and their names will be graven in stone in the streets and villages of a France restored in a liberated Europe to its full freedom and its ancient fame.

French defeat formed another chapter of sorrow to the British cause, for already the Norwegian campaign had ended in British withdrawal, the British army had been evacuated from Dunkirk, and Italian forces were powerful in the eastern Mediterranean, threatening the British base at Alexandria. With the fall of France all efforts of the French in the Mediterranean and in eastern Africa disappeared. Diplomats of the United States showed little faith that Britain could stand alone, inviolate, and suggested that the Royal Navy be based in Canadian and American east coast ports. These then were the desperate circumstances that Churchills government faced when it acted to seize the French port of Dakar in Senegal in order to keep it out of German naval hands as a U-boat base (it would be a threat to convoys round the Cape to the Middle East) and gain a critically important toehold of empire for General de Gaulle and those who called themselves Free Frenchmen. Admiral Raeder had stressed to Hitler the advantages Dakar would give Germany and the critical role it could play in upsetting British maritime supremacy. There was much at stake. But the whole went horribly wrong.

The generalities of the history of this campaign were known when the American historian Arthur Jacob Marder (19101980) came to examine it. Marder was then a high ranking historian of the Royal Navy, author of the magisterial five-part From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 19041919 (19611970; reprinted by Seaforth Publishing and Naval Institute Press, 20132014). After that works completion he turned to various high-intensity subjects in British naval history that were to take him through the inter-war years and right into the naval war against Imperial Japan. The volume here reprinted is one of these subjects (or rather two, for they are a pairing), large enough in complexity and documentation for significant historical analysis. They address subjects of perennial fascination.

It bears noting that Marder was barred from writing a general history of the Royal Navy in the inter-war period because his great rival, Captain Stephen Roskill, the official naval historian who had authored The War at Sea (three volumes of four, 19541962), had gone on to produce the two volumes entitled