To Dakar and Back

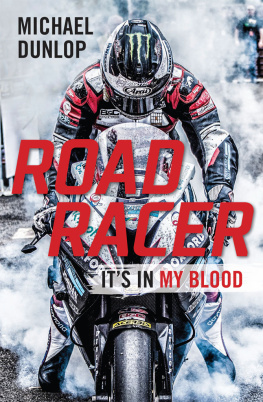

21 DAYS ACROSS NORTH AFRICA BY MOTORCYCLE

LAWRENCE HACKING

with Wil De Clercq

Copyright Lawrence Hacking and Wil De Clercq, 2008

Published by ECW Press

2120 Queen Street East, Suite 200, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4E 1E2

416.694.3348 / info@ecwpress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any process electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW Press.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Hacking, Lawrence

To Dakar and back / Lawrence Hacking with Wil De Clercq.

ISBN 978-1-55022-808-3

1. Hacking, LawrenceTravel. 2. Paris-Dakar Rally. 3. Motorcycle racingAfrica. 4. Motorcycle racingEurope. I. De Clercq, Wil II. Title.

GV1034.82.P37h33 2008 796.75092 C2007-904145-0

The publication of To Dakar and Back has been generously supported by the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada, by the Ontario Arts Council, by the Government of Ontario through Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit, by the omdc Book Fund, an initiative of the Ontario Media Development Corporation, and by the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (bpidp).

Developing editor: Michael Holmes

Cover and text design: Tania Craan

Typesetting: Gail Nina

Cover and spine photo: Maindru

Second printing by Transcontinental

All photos are from the collection of Lawrence Hacking, unless otherwise noted.

PRINTED AND BOUND IN CANADA

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

The rally to end all rallies

Chapter 2

Becoming an off-road racer

Chapter 3

Preparing for the Dakar

Chapter 4

Heading for the City of Lights

Chapter 5

Gentlemen and Ladies, start your engines

Chapter 6

The real Dakar

Chapter 7

Reality check

Chapter 8

Baptism by sand

Chapter 9

Halfway there

Chapter 10

Drowning on dry land

Chapter 11

The show goes on

Chapter 12

The dream almost comes to an end

Chapter 13

To Dakar and back

Chapter 14

Life after Dakar

For Mia, with her drawings

Acknowledgments

Any attempt at the Dakar takes an incredible amount of support its impossible to do it on your own. I would like to acknowledge the many family members, friends and companies that backed my effort to get to the starting line: you all helped me over that first hurdle. Since 2001 I have been involved in many other significant projects, and through thick and thin my friends have stood beside me. You know who you are, and I thank all of you sincerely.

My wife, Franoise, has the greatest spirit of anyone I know. Without her I cant imagine what path my life would have taken. I know it wouldnt be nearly as enjoyable, interesting or exciting. Thanks to her this book became possible.

Without Wil De Clercq To Dakar and Back would still be pages of notes sitting in a filing box beside my desk. He took that material and applied his craft. Thank you, Wil, for accurately conveying the message.

Thanks to the good people at ECW Press for believing.

Foreword

I awoke in a daze, listless and disoriented. Harsh sunlight streamed through the tents walls, nearly blinding my eyes. It seemed like I had dreamt the whole night that I was struggling through the desert on my bike, on foot, and even on camel-back. Id had very little sleep and I didnt want to get up. I could have used a blast of smelling salts to shake me out of my stupor but I knew I had to persevere and tackle the next stage. It was not a good frame of mind to be in to take on 535 kilometres of African desert. Everyone was in agreement that Stage 13, of which 513 clicks was competitive, would be one of the toughest ever seen in a Dakar. But toughest, like worse, is a relative term. I didnt want to think that anything could be tougher than what I had just endured.

The route we were to follow looped from Tidjika and back. It was the second of the marathon legs, in which no assistance from chase trucks was permitted. Not that that meant much to the privateers who had no team infrastructure to assist them in the first place. Once the special kicked off, we would have to navigate our way through a pass over a cliff, run along the base of the cliff, and climb back up on the plateau through the infamous Nega Pass. In between, everything the desert has to offer would have to be dealt with, including rutted and fast-winding tracks, and steep, soft dunes. Yeah, okay, this probably would be tougher than anything else I had to tackle so far. It wasnt an inviting prospect. I dragged myself out of my sleeping bag, got suited up, a challenge in itself, and quickly ate breakfast. Feeling like some kind of automaton, I crawled onto my motorcycle and rode out of the bivouac on the same road southwest of the airport to where Stage 12 had ended the night before. The timing tent served as the start line for the special. It was only a three-kilometre jaunt from the bivouac to the start and I was wishing it was a lot longer: I needed some time to thoroughly wake up so I could concentrate on riding. I felt I was too rushed and too tired to ride with a strong enough focus to guide the Honda through the hazards I would face. Something didnt feel right. Maybe I got dressed too quickly and didnt take the time to make sure everything was fitting right. Or some clothing was bunched up, or my toolbag was loose and hanging too low. Whatever the case, I was receiving warning signs that I should have heeded. Perhaps I should have taken the time to settle down and take a different attitude towards the day. I didnt dare admit to myself that I wanted to throw in the towel. Fortunately, I couldnt give myself the right excuse to do so. There was a carrot in front of me: the end of the rally at Dakar.

Only a few riders were gathered around the start area, which I thought was rather strange because there should have been quite a few more. I didnt have much time to dwell on it as I was directed straight up to leave. I was a few minutes late for my designated departure. It was hot and the sun hung high in a cloudless blue sky. The course followed a rocky road set by a bulldozer blade through the flat black rocks and sand. I rode fast but had trouble focusing on the terrain and corners. As usual, with the weight of the full fuel tanks, the bike was unwieldy and it was a struggle to stay on two wheels. Every -thing was exacerbated and exaggerated by fatigue. I had a bad feeling this wasnt going to be my best day. All my internal alarms were sounding, warning me to slow down or risk making a costly mistake. A little farther along, the trail wound past a dry riverbed that meandered in between short palm trees. Prior to this point I knew I was making some mistakes that played on my mental strength. I was riding like an absolute beginner, making errors from which I barely recovered. Then it happened: just 22 kilometres out on the course I missed a corner and slid across some rocks like an out-of-control railway car. The bike hit the ground hard. So did I! This was too absurd to comprehend. This was an error a rookie would make, not an experienced rider. I slowly got back on my feet and if I could have kicked myself I would have. I ached all over but fortunately I wasnt seriously injured. My eyelids weighed a ton: I could hardly keep my eyes open. I laboured to pick up my bike, which had never seemed so heavy before. From what I could see, other than a few more dents and scrapes, it had sustained no major damage. This could have been much worse. Being too tired to focus has cost many a rider his racing career or worse, his life. Maybe thirteen was bad luck after all; or maybe, considering I wasnt hurt and the bike was still intact, thirteen was good luck....