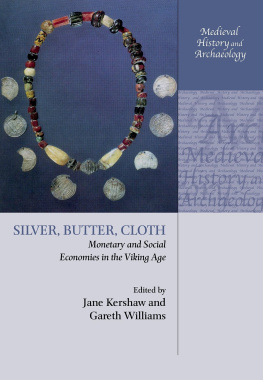

Published by

Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK

Oxbow Books and the individual authors, 2013

ISBN 978-1-84217-532-3

Front cover: An artists impression of Viking-Age Lincoln

at dawn (by Marcus Abbott)

This book is available direct from:

Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK

(Phone: 01865-241249; Fax: 01865-794449)

and

The David Brown Book Company

PO Box 511, Oakville, CT 06779, USA

(Phone: 860-945-9329; Fax: 860-945-9468)

or from our website

www.oxbowbooks.com

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Everyday life in Viking-age towns : social approaches to towns in England and Ireland, c. 800-1100 / [edited by] D. M. Hadley and Letty ten Harkel.

1 online resource.

Includes bibliographical references.

Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

ISBN 978-1-78297-009-5 (epub) -- ISBN 978-1-78297-010-1 (mobi (Kindle)) -- ISBN 978-1-78297-011-8 ( pdf) -- ISBN 978-1-84217-532-3 1. City and town life--England--History--To 1500. 2. City and town life--Ireland--History--To 1500. 3. Sociology, Urban--England--History--To 1500. 4. Sociology, Urban--Ireland--History--To 1500. 5. Great Britain--History--To 1066. 6. Ireland--History--To 1172. 7. Urban economics--History--To 1500. I. Hadley, D. M. (Dawn M.), 1967- II. Ten Harkel, Letty.

DA152.2

307.760942--dc23

2013026325

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Berforts Information Press Ltd, Eynsham

CONTENTS

1 Living in Viking-Age towns

David Griffiths

2 Towns and identities in Viking England

Gareth Williams

3 Viking Dublin: enmities, alliances and the cold gleam of silver

Emer Purcell and John Sheehan

4 Beyond longphuirt? Life and death in early Viking-Age Ireland

Stephen H. Harrison

5 From country to town: social transitions in Viking-Age housing

Rebecca Boyd

6 Childhood in Viking and Hiberno-Scandinavian Dublin, 8001100

Deirdre McAlister

7 Whither the warrior in Viking-Age towns?

D. M. Hadley

8 Aristocrats, burghers and their markets: patterns in the foundation of Lincolns urban churches

David Stocker

9 More than just meat: animals in Viking-Age towns

Kristopher Poole

10 No pots please, were Vikings: pottery in the southern Danelaw, 8501000

Paul Blinkhorn

11 Of towns and trinkets: metalworking and metal dress-accessories in Viking-Age Lincoln

Letty ten Harkel

12 Making a good comb: mercantile identity in 9th- to 11th-century England

Steven P. Ashby

13 Craft and handiwork: wood, antler and bone as an everyday material in Viking-Age Waterford and Cork

Maurice F. Hurley

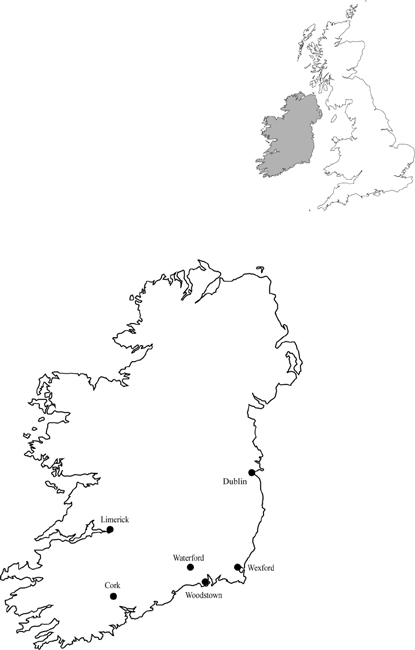

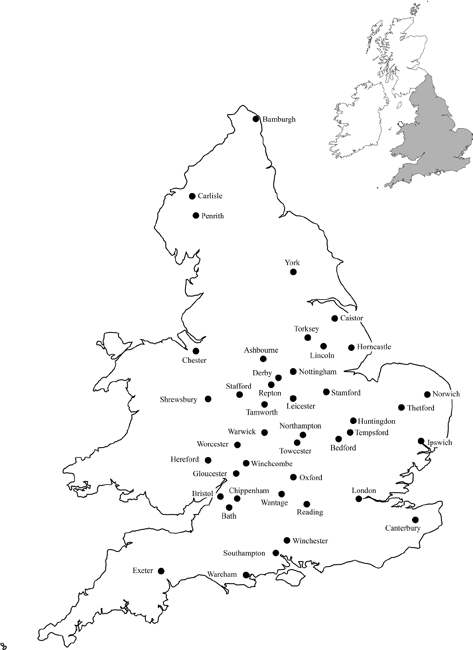

Locations of places referred to in the volume (drawn by Letty ten Harkel).

PREFACE

D. M. Hadley and Letty ten Harkel

The study of early medieval towns has frequently manifested itself as an investigation of urban beginnings and the search for broadly applicable definitions of urban characteristics. While the catalyst for urbanisation remains contested (e.g. Scull 1997; Valante 2008), the chronological development of towns has become more clearly understood over the course of the last quarter of the 20th century following large-scale urban excavations in advance of development (see Griffiths, this volume). Far less attention, in contrast, has been paid to the experience of living in towns, and, accordingly, this volume focusses on urban identities, as expressed through material culture, and on what characterised urban dwellers as different from their contemporaries in the countryside during the Viking Age (c. 8001100).

Towns: origins and definitions

The most influential definition of the town for early medieval archaeology in the British Isles is undoubtedly that provided in a study of Anglo-Saxon towns by Martin Biddle (1976, 99100) a generation ago. He suggested that the identification of Anglo-Saxon towns demanded the presence of at least three or four of the following characteristics: defences; a planned street-system; a market; a mint; legal autonomy; a role as a central place; a relatively large and dense population; a diversified economic base; plots and houses of urban type; a complex religious organisation; and a judicial centre. Over the years, Biddles definition of a town has been both adapted (e.g. Wickham 2006, 5916) and criticised, since some of his characteristics rely on historical evidence that is often not forthcoming in an early medieval context, while others (such as markets and judicial activities) can be found in undoubtedly non-urban contexts (Scull 1997, 271). In addition, scholars have commented on the difficulty of distinguishing between small towns and large villages, as both may share the same characteristics (Gardiner 2006, 24). Meanwhile, others have doubted the value of identifying defining characteristics for towns on the grounds that towns carry different meanings to different people at different times (Perring 2002, 9).

In the context of Scandinavian settlement, debates about towns have tended to focus on whether the settlers were the catalyst to the emergence of towns, or whether they merely added a new dimension to existing processes of urbanisation in England and Ireland (Hinton 1990, 926). It is widely acknowledged that when Scandinavian raiding and settlement commenced, English and Irish societies were essentially non-urban, even if in England the ruins of the largely deserted Roman towns still served as tangible reminders of a period when they were an integral part of everyday life. Nonetheless, in the centuries following the decline of these Roman towns, various settlement forms developed that have been identified as important stages in the re-emergence of urbanism. The middle Anglo-Saxon trading centres known as wics such as Ipswich (Suffolk), Hamwic (Southampton, Hampshire) and Eoforwic (York) undoubtedly provide the best examples (Scull 1997), although more recently Blair (2005, 2489) has argued in favour of middle Anglo-Saxon minsters as the forerunners to the late Anglo-Saxon town, on the grounds that they were focal points for manufacture and trade. Even more importantly in his opinion, the minsters corresponded more closely than wics to the idea of the civitas that was envisioned in Biblical texts and explored in early medieval writing, such as St Augustines De Civitate Dei (The City of God). As Blair (2005, 249) has observed, it was within the stone walls of Romano-British ruins, so enthusiastically adopted by monastic founders, that lay perceptions of special places in the landscape coalesced with literary ones of the heavenly and earthly Jerusalems. Ireland, in contrast, was not incorporated into the Roman Empire and therefore had no urban legacy comparable to that of England (Edwards 1990, 15). As a result, discussions about the origins of urban settlement forms have been less extensive, and largely restricted to considerations of the emergence of towns in the wake of Scandinavian influence in the 10th and 11th centuries (Valante 2008, 5780). It has certainly been argued in some studies that the Irish monastic settlements of the 7th and 8th centuries were every bit as complex as the