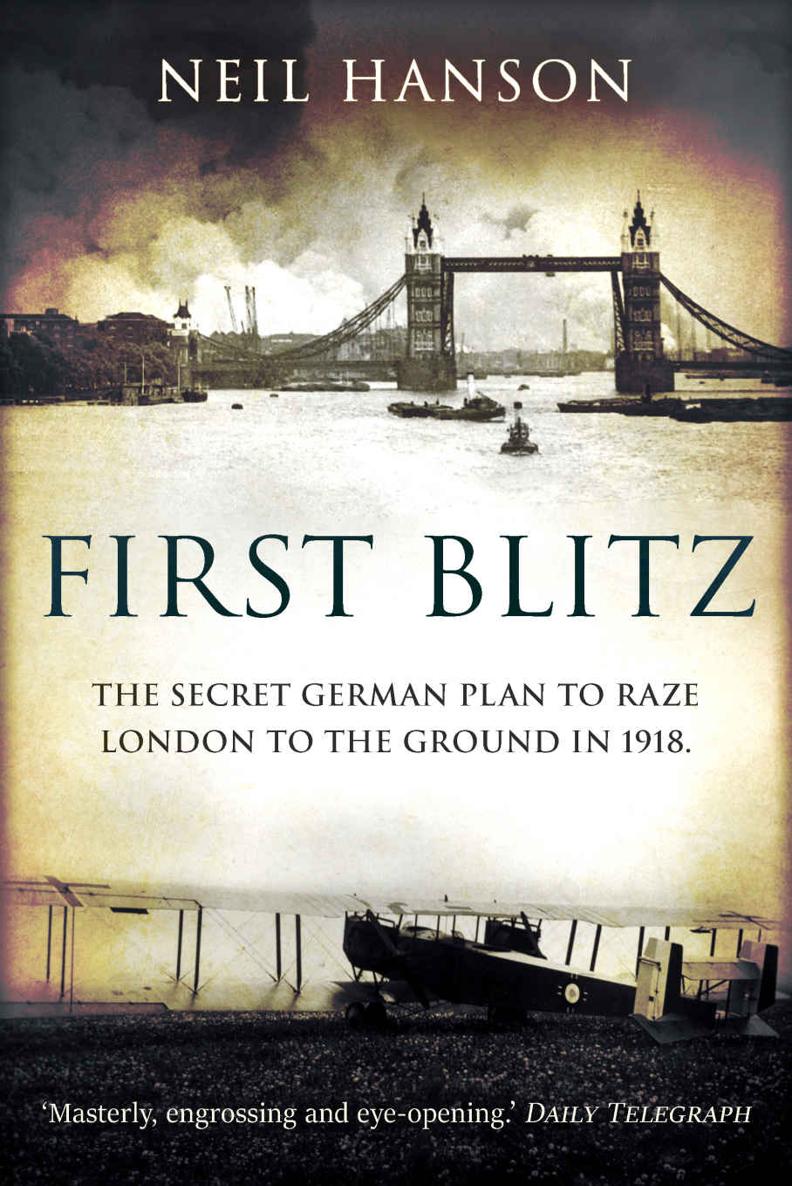

FIRST BLITZ

The Secret German Plan to Raze London

to the Ground in 1918

Neil Hanson

Neil Hanson 2008

Neil Hanson has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published in 2008 by Doubleday.

This edition published in 2021 by Lume Books.

For Lynn, Jack and Drew, who make everything worthwhile

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1 - THE FIRST BLOWS

CHAPTER 2 - ZEPPELINS OVERHEAD

CHAPTER 3 - TURKS CROSS

CHAPTER 4 - THE GOTHA HUM

CHAPTER 5 - FEVERISH WORK

CHAPTER 6 - A CITY IN TURMOIL

CHAPTER 7 - HOME DEFENCE

CHAPTER 8 - NIGHT-TIME EXCURSIONS

CHAPTER 9 - BRANDBOMBEN

CHAPTER 10 - THE BLITZ OF THE HARVEST MOON

CHAPTER 11 - THE SERPENT MACHINE

CHAPTER 12 - LONDONERS UNNERVED

CHAPTER 13 - AIR DEFENCE REVISITED

CHAPTER 14 - A FAILURE OF STRATEGY

CHAPTER 15 - GIANTS IN THE NIGHT SKY

CHAPTER 16 - THE WHIT SUNDAY RAID

CHAPTER 17 - THE ELEKTRON FIRE BOMB

CHAPTER 18 - LUDENDORFFS INTERVENTION

EPILOGUE

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CHAPTER 1

THE FIRST BLOWS

On Christmas Eve 1914, whatever might have been taking place across the Channel, Britons continued to enjoy a sense of domestic security, based on the inviolability of their island, that had been undisturbed for centuries. All that was about to change for ever.

At 10.45 that morning, local auctioneer and valuer Tommy Terson was in his garden in the shadow of one of the symbols of that inviolability, Dover Castle. As he was stooping to pick the sprouts for his Christmas dinner, he heard a loud droning sound. Looking up, he saw a dark shape emerging from the clouds drifting over the Channel. A German seaplane had dropped two bombs into the sea near the Admiralty Pier in Dover three days earlier, but this was the first aircraft that Tommy had ever seen.

He watched in amazement as it approached at an almost incomprehensible speed fifty miles an hour and passed directly overhead. He was still staring upwards, open-mouthed, when his garden erupted in a cloud of dust, smoke and flying metal. When he picked himself up, unhurt but for a few cuts and bruises, he saw a still-smoking crater, ten feet by four, where his vegetable patch had been. The windows of the surrounding houses had been shattered and Tersons neighbour had been blown out of the tree where he had been cutting holly for Christmas decorations. He also suffered only minor injuries, but the damage to the national psyche was rather more substantial. For the first time ever, the mainland of Britain had been subjected to an attack from the skies, its civilian population deliberately targeted.

Aircraft technology was in its infancy: it was only eleven years since the Wright Brothers first flight and just five since Louis Blriot had made the first airborne crossing of the Channel. The German Friedrichshafen FF 29 seaplane that carried out the raid on Dover was a canvas-and-wire biplane so crude it might almost be compared to the archaeopteryx of prehistoric days. It was operating at the absolute limit of its fifty-mile range, and so tight were the weight limits to get it airborne at all, even the four 2kg bombs it carried were a serious strain on its capacity. The pilot, Leutnant Karl Caspar, had nothing with which to defend himself other than the Mauser pistol he wore at his belt; but that would have caused him few concerns, for virtually every serviceable British military aircraft was with the British Expeditionary Force in France. Untroubled by any fighter or anti-aircraft gun, Caspar swung his aircraft around and disappeared back into the clouds drifting up the Channel.

The next day, Christmas Day, as most Britons were settling down to their festive meal, there was another, even more sinister attack. At 12.20 that afternoon the gun-crew of the Bartons Point anti-aircraft battery near Sheerness in Kent heard an aircraft approaching from the east. Five minutes later a German seaplane was spotted, flying at an altitude of 7,000 feet. Bartons Point and several other gun-batteries opened fire, but they recorded no hits. The gunners at Beacon Hill, Sheppey, were so overexcited by this first opportunity to engage an enemy that all they contrived to shoot down were their own telephone wires.

Oberleutnant Stephan Prondzynski flew on, following the Thames past Gravesend, Tilbury, Dartford and Erith, before spotting a Vickers Gunbus aircraft rising to intercept him. He could count himself very unfortunate to have happened upon the sole Home Defence aircraft in Britain at the time that could be described as a fighter, and he was forced to turn and fly back towards the coast as the Gunbus began firing bursts at him from its Maxim machine-gun.

As he climbed to escape the ponderous Gunbus, Prondzynski dumped his bombs on the thirteenth-century ragstone-and-flint village church of Cliffe, on the low chalk bluff of the Hoo peninsula, where a Christmas wedding was in progress. We heard a noise like someone banging carpets against the walls of the church The happy couple and the guests made an undignified rush for the carriages and home. Bombs had been dropping; we could not partake of the wedding breakfast because some of the guests fainted. Their discomfiture would have been of far less concern to the Government than the knowledge that when he turned back the German raider had been within five miles of Woolwich Arsenal and the start of Londons sprawling docklands. The implication was clear: the nations vital industries and the capital itself were now within range of German bombs.

The French authorities were already aware that Paris, only sixty miles from the front lines, was a target for German bombers. On 13 August 1914, just ten days after Germanys declaration of war with France, a Taube aeroplane had dropped two or three small bombs on the Quai de Valmy in Paris the first ever attack on a capital city by an aircraft. It also dropped a leaflet that read Parisians, attention! This is the greeting of a German aircraft. In a second raid on 30 August, five bombs fell on Paris, killing three civilians, and in a further attack a few days later another German pilot, Hauptmann Keller, dropped six 10kg bombs on the Gare de lEst. Undisturbed by defensive fire and aircraft, I could let myself go and be enchanted completely by the sight of the capital in the autumn sun a strangely poetic description of the city he was doing his best to destroy. Afternoon raids became such a regular event during the following months that Parisians would assemble along the River Seine or another good viewing place to watch for the arrival of the German plane, which became known as les cinq heures du Taube .

The civilized worlds attitude to the bombing of cities far removed from the front lines of a conflict had been expressed in resolutions passed by Peace Conferences held at The Hague in 1899 and 1907, and was reiterated at a further conference after the First World War was over. Aerial bombardment is legitimate only when it is directed against a military objective, i.e. an objective whereof the total or partial destruction would constitute an obvious military advantage for the belligerent Aerial bombardment for the purpose of terrorising the civilian population, of destroying or damaging private property not of a military character, or of injuring non-combatants, is prohibited.

Military commanders were often less concerned with niceties of legitimacy and morality than their political masters, and one of the first significant theorists of air power, the Italian General Giulio Douhet, took a more pragmatic stance on the question of bombing cities. The complete destruction of the objective has moral and material effects we need only envision what would go on among the civilian population of congested cities once the enemy announced that he would bomb such centres relentlessly, making no distinction between military and non-military objectives.