Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Leigh M. Moring

All rights reserved

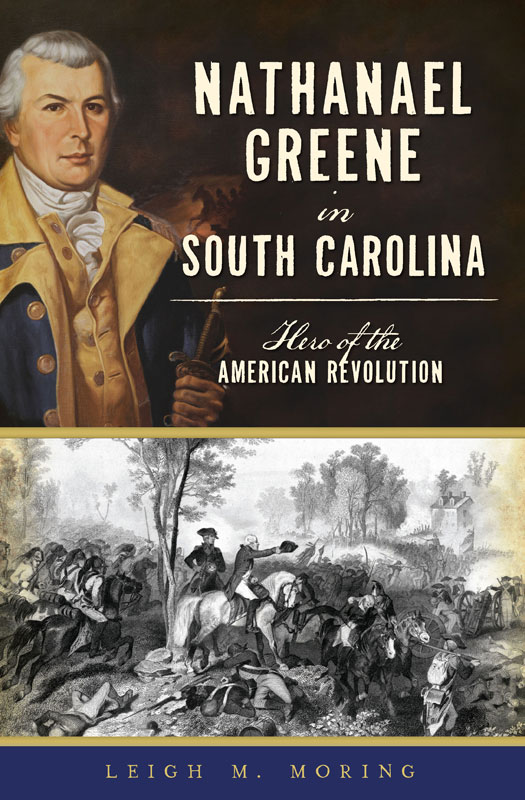

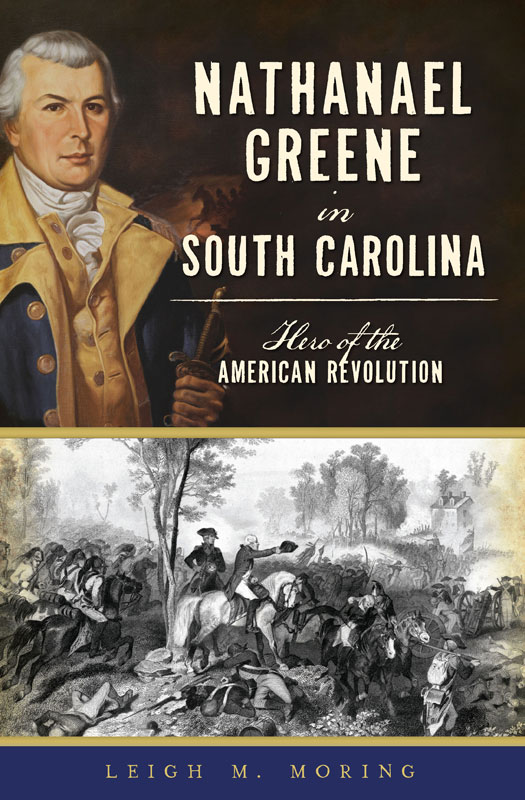

Cover images: The Battle of Eutaw Springs, steel engraving depicting General Greene pointing his army onward on the morning of September 8, 1781. Original painting by Chappel, published by Johnson, Fry and Company in New York, 1859. Courtesy of the Library of Congress; painting of Nathanael Greene by Robert Wilson. Courtesy of Robert Wilson Fine Art.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.43965.891.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016948311

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.686.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For my parents, Platte and Susan Moring.CONTENTS

PREFACE

Nathanael Greene assumed command of the southern campaigns during the American Revolution following previous failed leadership in December 1780. George Washington charged Greene with removing the British from the South, which he was ultimately able to do, but not until 1783. In this book, discover Greenes operations in South Carolina with a focus on the events that directly led to his liberation of Charleston in 1782 and the struggles he faced in achieving this feata final victory that involved much toil, tears and sweat, but one that he achieved with little bloodshed. Historians and educators tend to overlook the period from the British Surrender at the Battle of Yorktown on October 19, 1781, to the evacuation of Charleston in December 1782, so this book fills a gap in the existing chronicles of the period and presents new findings. Greene dealt with supply and manpower shortages, faced Loyalists and liberated slave units fighting for the British and met opposition from his peers in the political dealings of South Carolina. This book introduces a new perspective on an important period in Greenes command by explaining how the Revolutionary War really ended. Readers should note that until Charleston was incorporated as an American city on August 13, 1783, the city was called Charles Town. The name was changed to remove traces of its ties to Britain. For the purpose of clarity, the city will be referred to by its modern name of Charleston in this book, but Greene and his contemporaries would have written and called it Charles Town before that date in 1783.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are many people I would like to thank for helping me with the publication of my first book. First, I want to thank Dr. David Preston. Dr. Preston was my graduate thesis advisor at The Citadel. I came to Dr. Preston wanting to write about one of my personal heroes, Francis Marion, but he suggested I take a look at Nathanael Greene. He recommended books to use for research and was always happy to listen to any theories and new information I had found in Greenes papers. Dr. Preston was a wonderful thesis advisor and encouraged me to lengthen and publish my thesis into a book.

The staff at my place of business, Historic Charleston Foundation, has been great throughout this whole process. Their support during this journey is much appreciated.

As the Education Coordinator for Historic Charleston Foundation, I have the privilege of working with many historic sites and museums in the Charleston area. I am grateful for the interest and excitement that many of these educational professionals have shown in this project and their willingness to assist me. In particular, Jennifer McCormick at The Charleston Museum was helpful, as she allowed me to examine actual correspondence between Greene and his contemporaries from the museum archives. Also, John Young at the Powder Magazine served as my expert on Charleston and answered many historical questions that came up in my research.

Lastly, I would like to thank my parents, Platte and Susan Moring, for encouraging me to pursue my interest in history from a young age. Family trips to historical sites fed my passion and fueled my desire to learn all I could about the past. My parents made my education possible, so I really owe this book to them. I also want to thank my friends Brittany Tolleson, Callie Neal, Manning Mullikin, Eva Cheros and Casey Anne Attaway for their support and encouragement. I am truly grateful for all of my family, friends, past teachers and colleagues, for they have all had a hand in this project.

INTRODUCTION

We have been beating the bush and the General has come to catch the bird.

Greene on the impending surrender at Yorktown

On September 29, 1781, Major General Nathanael Greene wrote from South Carolina to his friend Henry Knox, who was in Virginia with General Washington. The French and American armies had begun to besiege Lord Charles Cornwalliss British forces at Yorktown. Greene encouraged Knox that the prospect is so bright and the glory so great that I want you to be there to share in them. Although everyone seemed transfixed on the Siege of Yorktown, Greene had already earned his own laurels in the Carolinas. Greene would not be present at Cornwalliss surrender, but he certainly deserved credit for exhausting the British army and sending it toward eventual defeat in Virginia. But before Greene could rest and enjoy the new country he was liberating, he first had to handle the still-powerful British army that remained in South Carolina. The first step in that process was the clash at Eutaw Springs in September 1781, the last major battle of the war in the state, which was pivotal in pushing the British back to Charleston.

Earlier that month, Greene had just taken his army from its encampment at Burdalls Plantation and marched toward Eutaw Springs. Before this march, Greenes mission was to end British control in the South Carolina upcountry, starting with recapturing the town of Ninety-Six. Greene felt that this might be the final offensive of the Revolutionary War in South Carolina. For the entire month of May 1781, Greene and his men laid siege to that fortified village. Only after he learned that more British reinforcements were landing in Charleston did he assault the fort and retreat to Charlotte. Lord Rawdon, the British commander, heavily pursued Greene for several days. Greene was used to evading the British, and he knew he could tire out his opponents through his usual strategy of long marches. Just as Greene expected, Rawdon and his men were exhausted by the pursuit and had to retire to Charleston, where Rawdon left command of his forces to British Colonel Alexander Stewart.

Painting of Nathanael Greene by Robert Wilson. Courtesy of Robert Wilson Fine Art.

Greene decided at this point to head toward Charleston as well to face the remaining British forces, all garrisoned in one of the last British-occupied southern towns. Stewart and his two thousand men were in search of Greene and left Charleston to meet them on their way. They camped at Eutaw Springs just seven miles from where Greene was marching on that fateful September day in 1781. Greene had the weight of the Revolution in the South on his shoulders, and he had grown weary of the wars destruction. He often thought of his wife at home in Rhode Island and wrote as much as he could to her. Nathanael had married Catharine Caty Littlefield in 1774 and had five children with her. He knew that she had her own hardships in raising the children and managing the finances on her own. But he knew it was his duty to his country to continue fighting with Washington. He wrote to Caty: