Published with the assistance of the Fred W. Morrison Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2017 Rod Andrew Jr.

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

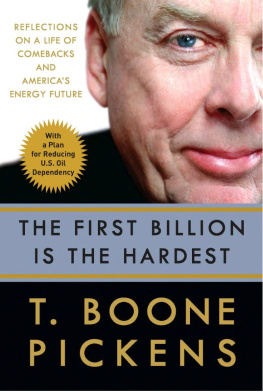

Jacket illustration: portrait of Andrew Pickens courtesy of the Portrait Collection of Historic Properties, Clemson University.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Andrew, Rod, Jr.

Title: The life and times of General Andrew Pickens : Revolutionary War hero, American founder / Rod Andrew Jr.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016036179 | ISBN 9781469631530 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469631547 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Pickens, Andrew, 17391817. | GeneralsUnited StatesBiography. | LegislatorsUnited StatesBiography. | United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Biography. | United StatesHistory17831865Biography.

Classification: LCC E207.P63 A63 2017 | DDC 975.7/03092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016036179

Preface

The old gentleman rode straight and stiff in the saddle into the village of Pendleton, South Carolina, one day in the late 1790s. He was about five feet ten inches tall, quite lean & slenderquite ugly, one man remembered. He was dressed simply and neatly, wearing a wide beaver hat. Virtually every person who noticed him would have immediately recognized him as General Andrew Pickenshero of the Revolution, successful merchant and planter, respected judge, legislator, and Indian treaty commissioner. The general dismounted and conducted his business quietly and modestly. He conversed but little, the observer noted, and by no means freely; except with particular friends, and of these he was remarkably choice. And even with them, he was slow and guarded. Even on the few occasions when Pickens addressed other citizens publicly (and this was not one of them), his words were few, simple, and direct. There was no soaring oratory, no classical references, no rhetorical flourishes.

Pendleton itself was little more than a glorified crossroads, with a courthouse and a few stores and cabins around the town square and a Presbyterian church about three miles away. Located in the far northwest corner of the state, Pendleton was on the outer edge of white settlement in the area. Only fifteen years before, it had been Cherokee country, a place where, in time of war, no white man, woman, or child could have safely dwelled. Many of the white inhabitants of the area were veterans of the brutal, merciless, and seemingly never-ending war that had driven those Indians away. It was the same war that, in their view, had defeated the bloodthirsty, treasonous Tories and the red-coated brutish soldiers of a distant, hated king. Already they had forgotten the treachery and butchery that they themselves had inflicted on their Indian and Tory neighbors, but they did remember the courage and fortitude it had taken to prevail, and no man had exhibited more valor, honesty of purpose, and implacable will than the old general himself.

He was one of them. Like Pickens, many of his neighbors were ethnically Scotch-Irish, nearly all of them Presbyterians or members of other dissenting, non-Anglican sects. Many of their parents and grandparents had come from the north of Ireland and the wild, lawless borderlands between northern England and southwestern Scotland. For generations their ancestors had fought English kings, lords, and bishops, as well as rival countrymen, for survival, for vengeance, and for the right to worship as they chose. Many later migrated to Pennsylvania, where their quarrelsome ways quickly exhausted the patience of the peace-loving Quakers. From there they moved south and southwest into the sparsely occupied mountain valleys and foothills of Virginia and the Carolinas, attempting to tame the frontier as they carved out their own place with frequently hostile Indians on one side and condescending, neglectful colonial assemblies on the other.

Also like the people around him, the general had not started life with vast lands, wealth, or slaves. He enjoyed few educational advantages; he was functionally literate but not much more. Then, either by Gods favor or his own merit, it seemed, he had prospered, accumulating wealth and profiting by the spread of slavery into the western portions of the state. Even as slavery was growing and making some in their region richer, however, there was debate and soul-searching within their churches as to what Gods will might be when it came to owning other human beings.

Religion was important to these Calvinists and evangelicals, formerly dissenters to the established church. Many, like the general, had been born or come of age while the fires of the Great Awakening were still smoldering in the American colonies, and the new nation was on the verge of a second national revival that would have an even greater impact than the first. They still believed in a God who would hold them accountable for their conduct, both as individuals and as a people, but who also offered forgiveness and new life through repentance and faith. The general himself had been a devout Presbyterian all his lifesober, upright, and pious. In every new place he settled, as he helped push the frontier westward, he had been a founding member and elected elder of the local congregation, just as he was at the church on the outskirts of town.

While the recent struggle had inflicted all the horrors of civil war on the South Carolina backcountry, there had been much of the heroic in the generals and the peoples fight for republican liberty. At one point, by the summer of 1780, South Carolina was essentially conquered by men loyal to the king. Many of those on the Whig side were arrested, hounded from their homes, or forced to take oaths of allegiance. When the British occupation proved to be more onerous than promised, when their oaths of allegiance did not protect them from oppression, they had renounced their assurances to the kings officers and risen up again. All over the province, but especially in the backcountry, small farmers and frontiersmen turned out in large numbers to avenge the attacks of the Tories and the British soldiers and their Indian allies. Battle by battle, ambush by raid, led by fierce, determined men like the general, they had retaken the state and joined in the fight to liberate their neighboring states of Georgia and North Carolina. Their determination was decisive in the ultimate outcome of the American Revolution. Pickens had made a name for himself as a militia officer during the first five years of the conflict. After the British overwhelmed Whig resistance in the spring of 1780, Pickens had accepted parole like most others. In fact, when patriot resistance sprang back to life that summer, Pickens had been slow to renounce his oath to the British authorities, strictly observing his parole until his own family and plantation were attacked by marauding Tories. Then he had rejoined the cause and become one of the most important militia leaders on the southern frontier, playing a leading role in victories at Cowpens, Augusta, Eutaw, and dozens of smaller actions.