This book was published with the assistance of the Fred W. Morrison Fund for Southern Studies of the University of North Carolina Press.

2008 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Designed by Kimberly Bryant

Set in Quadraat by Keystone Typesetting, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Andrew, Rod.

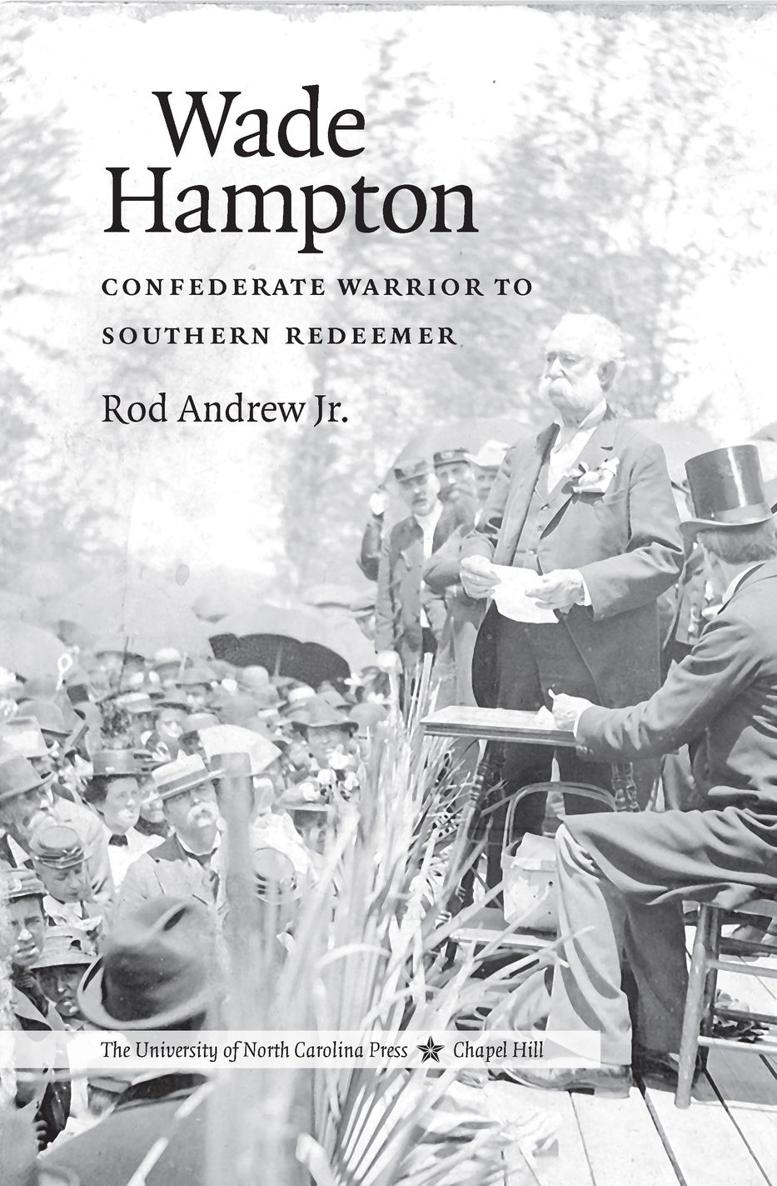

Wade Hampton : Confederate warrior to southern redeemer / Rod Andrew Jr. p. cm.(Civil War America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8078-3193-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-0680-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

eISBN : 29-4-000-01963-7

1. Hampton, Wade, 1818-1902. 2. GeneralsConfederate States of AmericaBiography. 3. Confederate States of America. ArmyBiography. 4. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Cavalry operations. 5. GovernorsSouth CarolinaBiography.

6. LegislatorsUnited StatesBiography. 7. United States. Congress. SenateBiography. 8. Reconstruction (U.S. history, 1865-1877) 9. South CarolinaPolitics and government1865- 1950. I. Title.

E467.1.H19A64 2008 973.742dc22

2007045836

cloth 12 11 10 09 08 5 4 3 2 1

paper 16 15 14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

PREFACE

Wade Hampton III of South Carolina was one of the most beloved, trusted, hated, and feared men of his time. Though today many Americans outside his native state have no idea who he was, virtually every American of his own day did and had strong opinions about him. His military and political careers, as well as his personal life, illuminate many features of the transition from the Old South to the New. As a Confederate military hero, victor over the Republican government in Reconstruction South Carolina, governor, U.S. senator, and cultural icon of the Lost Cause, Hampton was the most important figure in late nineteenth-century South Carolina.

I have two goals for this book. One is simply a better understanding of Hampton himself. Despite his tremendous impact on the events of his own day, he remains one of the most misunderstood figures of his time. Until at least the middle of the twentieth century, biographies of Hampton were exercises in hero worship written by amateur historians or by Hamptons friends and former Confederate comrades. Later historians have avoided biographical portraits of Hampton and instead studied his political stances and activities, especially as they dealt with race relations. Unfortunately, these scholars, too, have often missed the mark in their analysis of Hampton. Concerned more with broad patterns in southern history than biography, they have not considered how Hamptons background, biases, and personal tragedies may explain his words, actions, and apparent inconsistencies. He has appeared in some studies as a racial moderate; in others, as a hypocrite who publicly preached moderation while secretly sponsoring white terrorism. Hampton has emerged as a cutout cardboard figure supporting this position or that, rather than a man driven by noble instincts, painful life experiences, and human failings.

I believe that Hamptons personal life experiences, rather than being irrelevant or incidental to his military and political role, are instead central to it. His personal background, tragedies, humiliations, and search for vindication, in fact, explain much about the history of the American South in the era of the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Redemption. As I relate the story of Hamptons life in a chronological fashion, therefore, my other goal will be to use his story to clarify our understanding of major topics in southern historypaternalism, honor, chivalry, the impact of war on individual soldiers and loved ones at home, the reasons why many Confederate soldiers continued to fight as long as they did, Reconstruction, racism and white supremacy, and the myth of the Lost Cause. The war chapters also serve to trace Hamptons development and maturity as an officer; Hampton was one of the few Civil War officers who had no prior military experience but who advanced to the rank of lieutenant general and were competent combat leaders. My hope is that the biographical perspective, used in the study of a major figure whose lifespan stretched from before the Missouri Compromise of 1820 to the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, will amplify our understanding of all those topics.

The first chapters of this book rely heavily on three themes to explain the cultural influences and socialization of Hampton in the first half of his life. Paternalism, honor, and chivalry are terms that historians have often used to define the ideals of men and women of Hamptons class and time. I do not attempt to redefine those terms here, but the reader has a right to know my working definitions of them within the pages of this book.

For some academic readers, my use of the term paternalism will prove the most problematic. I am aware that a growing body of current scholarship treats claims of the southern master class to be paternalistic providers and protectors as masks for oppression. White male slaveholders, it is argued, used rhetoric about principled leadership and protection of social inferiors, including slaves and women, to justify their own status and social power. I do not question the notion that many members of the antebellum southern gentry did exactly that. A close study of the life of Wade Hampton III, however, leads to the inescapable conclusion that southern white men were not always cynical and self-serving when they sought to be protectors and providers. Born into a world of wealth, security, and privilege, Hampton believed that elite, educated men like himself had the right and responsibility to lead and govern. In return, they had paternalistic responsibilities to their social inferiors, including white women and dependent black laborers. For Hampton not to treat the Negro with humanity, considering their differences in status, social power, and supposed intellectual ability, would reflect dishonor upon himself as a member of the elite. It would put him on a level with the petty, poor whites around him, unrefined by culture, education, and magnanimity; or with unscrupulous carpetbaggers, who allegedly made irresponsible promises to black men for opportunistic reasons. I argue that, unless we take Hamptons sense of paternalistic obligation seriously, it is impossible to explain his seemingly contradictory postwar political behavior. Frankly telling both black and white audiences that he believed blacks to be culturally and intellectually inferior, he nevertheless went far beyond many of his white contemporaries in promising legal protections and basic civil rights to African Americans. He knew that he risked paying a high political price among would-be allies for obstinately holding this ground, and pay it he did. What was most tragic about paternalism in his case is that no matter how benevolent Hampton might try to be, his speeches and policies could never lead to racial justice or equality, since paternalism itself was built on the assumption of black inferiority.