All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Dawson, Gowan, author.

Show me the bone : reconstructing prehistoric monsters in nineteenth-century Britain and America / Gowan Dawson.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-33273-4 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-226-33287-1 (e-book) 1. PaleontologyGreat BritainHistory19th century. 2. PaleontologyUnited StatesHistory19th century. 3. PaleontologistsBiography. I. Title.

QE 705. A 1 D 39 2016

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Cuviers Law of Correlation

In the crowded lectures he gave at New Yorks College of Physicians and Surgeons each winter during the 1810s, the politician and polymath Samuel Latham Mitchill regaled his audiences with an audacious test of his knowledge of natural history. Already famous for his flamboyance and erudite eccentricities, Mitchill would declare:

Ex pede Herculem, said the ancient artist, I can tell Hercules from his toeEx dente animal, says Cuvier, give me the bone, and I will describe the animalI go further... show me a single scale, and I will let you know the fish that owned it.

Having honed his ichthyological expertise in the pungent fish markets of Lower Manhattan, Mitchill avowed that his powers of identification surpassed the classical claimgenerally attributed to the Greek mathematician Pythagoras rather than an unnamed ancient artistthat the pagan divinity Hercules could be measured, proportionally, solely by his foot. This distinctively American boosterism, however, would have important implications for the study of natural history, and especially the fledgling science of paleontology, on both sides of the Atlantic.

It is uncertain whether Cuvier actually made the declaration Give me the bone, and I will describe the animal that Mitchill attributed to him. It does not appear in any of his published writings, nor in his extant correspondence, and if he uttered it at all, it could only have been as a conversational remark or an oral aside during a lecture. This claim was articulated in the Discours prliminaire from Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles (1812), an English translation of which Mitchill edited for American readers in 1818. Despite Mitchills evident embellishment, it was not long before the apocryphal story of Cuviers daring boast spread across the Atlantic.

It was even accepted in France, where, in the early 1850s, the politician and erstwhile prime minister Adolphe Thiers translated Mitchills Americanization of Cuvier back into French (Donnez-moi un os...), perceiving such hauteur as a source of Gallic national pride.

In particular, practitioners of the nascent science of paleontology, a term coined in 1822 to distinguish the study of fossil organisms from geologys traditional emphasis on rock strata, were heralded as scientific virtuosos, sometimes even as veritable wizards, who could resurrect the hitherto unknown denizens of the ancient past from merely a glance at a fragmentary bone ( Such extraordinary displays of predictive reasoning were accomplished, it was claimed, through the law of correlation, which Cuvier formulated following his arrival in Paris in 1795 only months after the end of the revolutionary Reign of Terror. This law was an essential component of the new approach to comparative anatomy that Cuvier first adumbrated in Leons danatomie compare (18001805), but it subsequently became still more integral to the paleontological practices presented in his Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles. It proposed that each element of an animal corresponds mutually with all the others, so that a carnivorous tooth must be accompanied by a particular kind of jawbone, neck, stomach, and so on, that facilitates the consumption of flesh, and equally cannot be matched with bones and organs adapted to a herbivorous diet. As such, a single part, even the merest fragment of fossilized bone, necessarily indicates the configuration of the whole. It was on this basis that Cuvier could allegedly declaim: Give me the bone, and I will describe the animal.

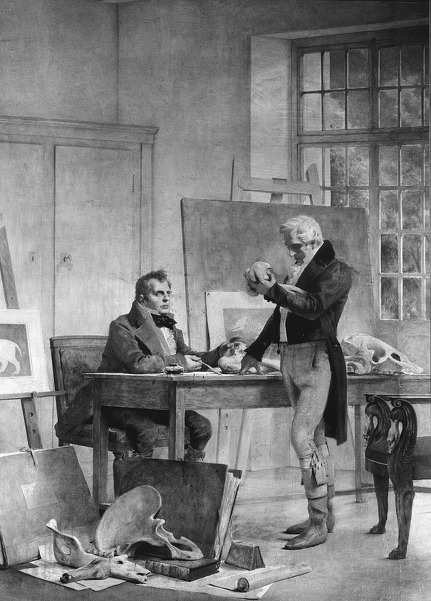

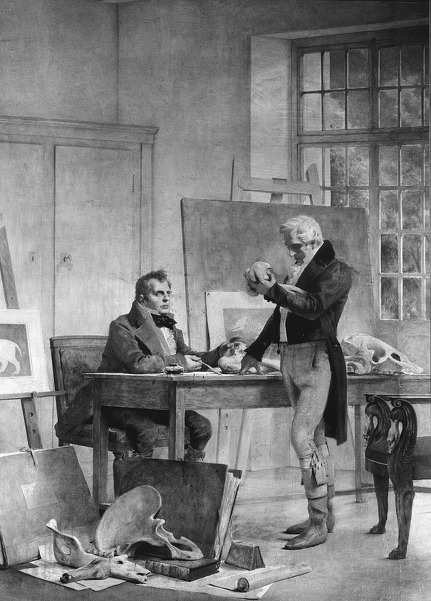

FIGURE I.1. Thobald Chartran, Cuvier runit les documents devant servir son ouvrage sur les ossements fossiles (1823). Oil on canvas, circa 1888. Sorbonne, Paris. This late nineteenth-century painting, part of a sequence of nine portraits of French scientific heroes, shows Cuvier focusing intently on a single bone, presumably mentally reconstructing the creature from which it came, while preparing the second edition of his monumental work on fossil quadrupeds Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles (182124). 2014 White Images / Scala, Florence.

Cuvierian Mania

The law of correlation, which will be discussed in more detail in

The depredations of the Reign of Terror had left a power vacuum in postrevolutionary intellectual life, and Cuvier, having rapidly established his reputation in Paris, compared his predictive powers to those of the mathe maticians who dominated the French capitals scientific institutions. He insisted that the organic law of correlation was a rational axiom no less unerring than the fundamental principles of physical sciences such as astronomy and chemistry. In order to sustain such claims, natural history had to exhibit the same precision and methodological rigor as other mathematically based sciences, and Cuvier was disdainful of the imprecise, descriptive accounts of nature with which his predecessors at the Musum dhistoire naturelle had engaged mass audiences, considering it demeaning to cultivate such a public following.claims to be able to reconstruct an entire animal from only a single boneeven if never quite as dramatic as Mitchills New York lectures impliedcaptured the attention of audiences far beyond scientific specialists, transforming the law of correlation from a recondite concern of anatomical experts to one of the most celebrated, or at least widely invoked, scientific axioms of the nineteenth century.

Although it was formulated at a time when, following the Revolution and then the rise to power of Napoleon, France and Britain were almost continuously at war, it was across the Channel that Cuviers law of correlation took particular hold. Indeed, Knox exasperatedly diagnosed a veritable Cuvierian mania among his compatriots in the late 1830s.