ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: WORLD EMPIRES

Volume 12

THE BUILDERS OF THE MOGUL EMPIRE

THE BUILDERS OF THE MOGUL EMPIRE

MICHAEL PRAWDIN

First published in 1963 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1963 George Allen & Unwin Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-47911-1 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-351-00226-4 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-48562-4 (Volume 12) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-351-04856-9 (Volume 12) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

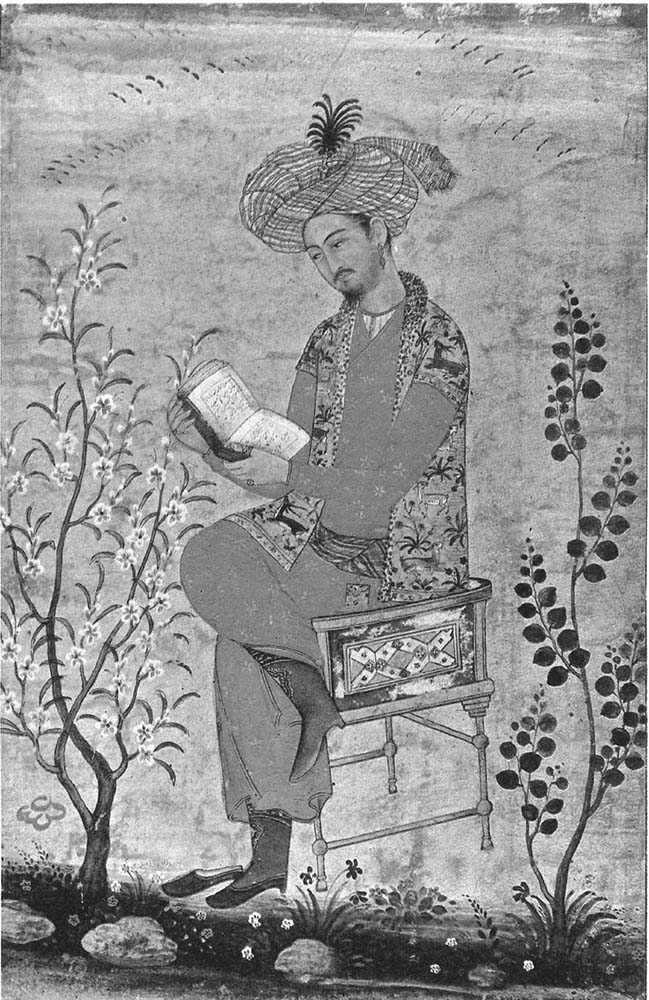

THE EMPEROR BABUR READING

MICHAEL PRAWDIN

THE BUILDERS OF THE MOGUL EMPIRE

London

GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD

RUSKIN HOUSE MUSEUM STREET

FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1963

This book is copyright under the Berne convention. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1956, no portion may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiry should be made to the publishers.

George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1963

CONTENTS

Babur reading a book

O VER two and a half centuries had passed since Jenghiz Khan, out of the vastness of East Asia, had irrupted into the lands of the Sir Darya and Amu Darya and smashed the Moslem Empire then stretching from the Pamir to beyond the Caspian Sea. Forty years later the Mongols, under Jenghiz Khans grandson Hulagu, had subjugated all the realms to the west of the Oxus, nearly as far as the Mediterranean, and were only stopped by the Egyptian Mamelukes from conquering the whole of Syria. Then, in the space of a few generations, the Empire of the Il-Khans, which Hulagu had founded, changed its character, as had happened so often in the history of western Asia, where the settled world of Persian civilization had absorbed wave after wave of invaders from the steppes. Hulagus descendants, and more and more of the Mongolian nobles, went over to Islam; the nomad rulers surrounded themselves with scholars and poets, building palaces and towns to their glory, and spending their time in festivities or wars against one another. Real power was wielded by the viceroys and amirs in the various provinces. As soon as one of them felt strong enough, he discovered some descendant of Jenghiz Khan, proclaimed him Khan, and in his name started wars against his neighbours in the hope of annexing their provinces.

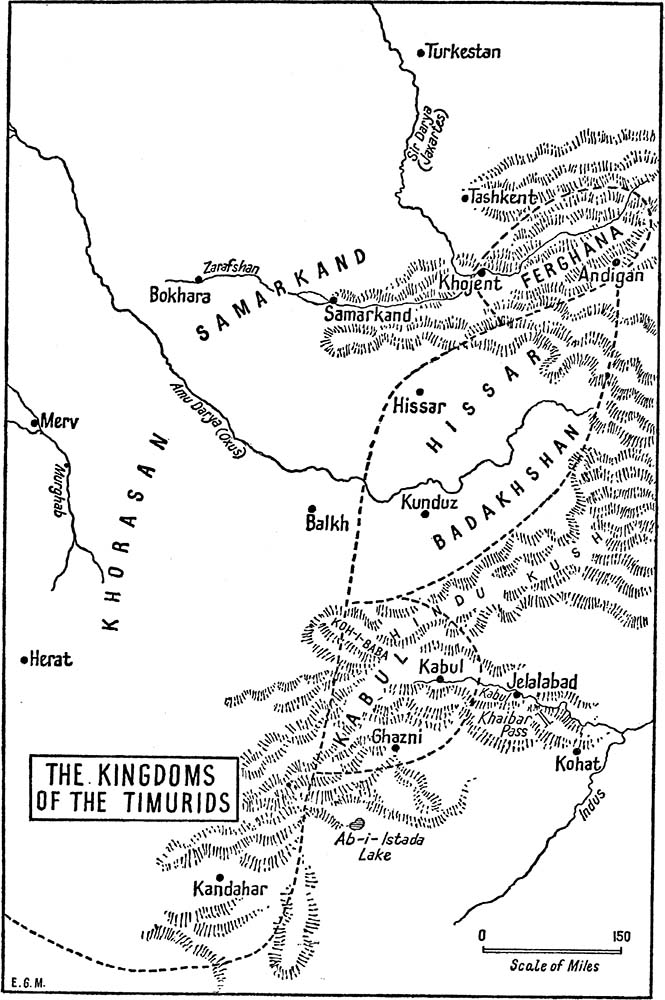

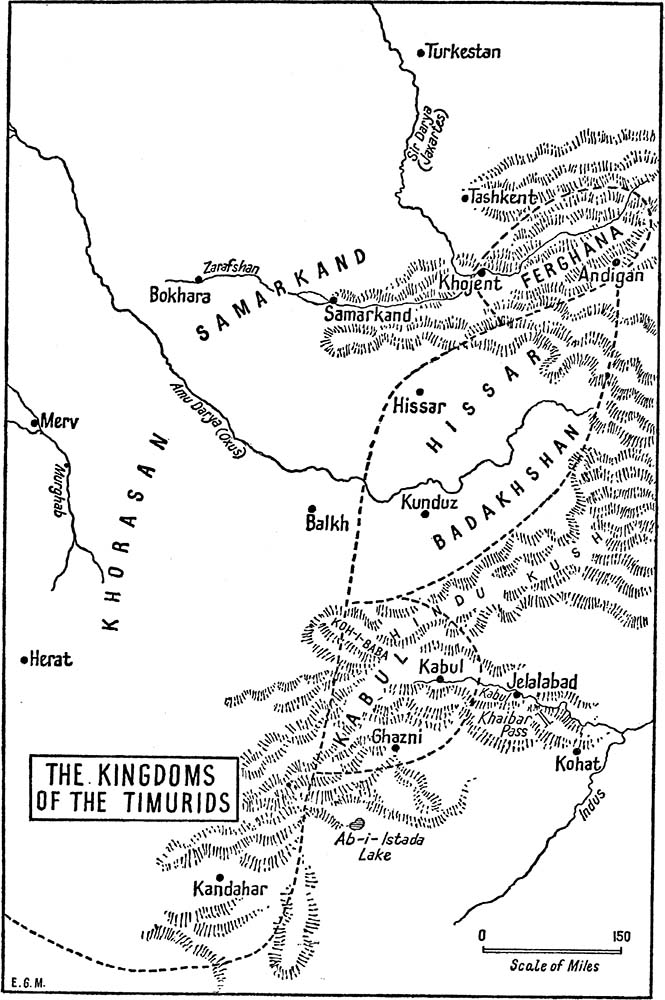

It was about a century after the creation of Hulagus Empire that in the region of the Amu Darya (the Oxus) and the Sir Darya (the Jaxartes of old) a new power arose. This region, Jenghiz Khans original target, did not really belong to Hulagus Empire. The land beyond the Amu Darya had been allocated to the realm of Jagatai, Jenghiz Khans second son, whose central Asian empire was intended to form a bridge between China and Western Asia. But the eastern half of Jagatais realm, Turkistan, poor in cities and rich in steppes, remained a typical nomad land, while its western part, Transoxiana, between the Amu Darya and Sir Darya, was populous, industrious, and culturally and economically much more akin to the empire of the Il-Khans which bordered it to the south-west.

In this frontier land between Iran and Turan a chieftain of the Barlas Turki-tribe, Timur, had himself proclaimed Grand Amir of Transoxiana in the year 1369, and with a Jenghizid as nominal Khan started on the superhuman task which he had set himself: that of re-establishing Jenghiz Khans empire. When he died thirty-six years later, he left what is known in Europe as Tamerlanes Empire, reaching from the Aral Sea to the Arabian Sea and from the Mediterranean nearly to the Altai Mountains. But he had not, like Jenghiz Khan, created a warrior nation, since he made his conquests with an army of mercenaries held together in the main by his personality and the expectation of spoils. And in spite of the frightful destruction which accompanied his campaigns, it was the Iranian-Islamic civilization which not only survived but re-emerged from the slaughter strengthened and enhanced.

Timurs descendants felt themselves heirs more to a culture which they wanted to enjoy and foster than to the ambition of world conquest. Fighting one another for the throne, for a province, for a fief they often sought help from the nomadic warriors of Turkistan or of the northern steppes against their immediate neighbours, only to discard their helpers at the moment of success in order to pursue a life of culture and pleasure as the previous rulers had done. Proud of their learning and their manners, they considered themselves not Mongols but Turks, superior to the rough Mongolian riders of the steppes. And the nomads, whether they came from outside the province or were wandering with their cattle in its hills or wastes, felt themselves in no way bound to the man by whom they had been engaged for a campaign. When the fortunes of battle turned against him, they simply plundered his camp before fleeing themselves.