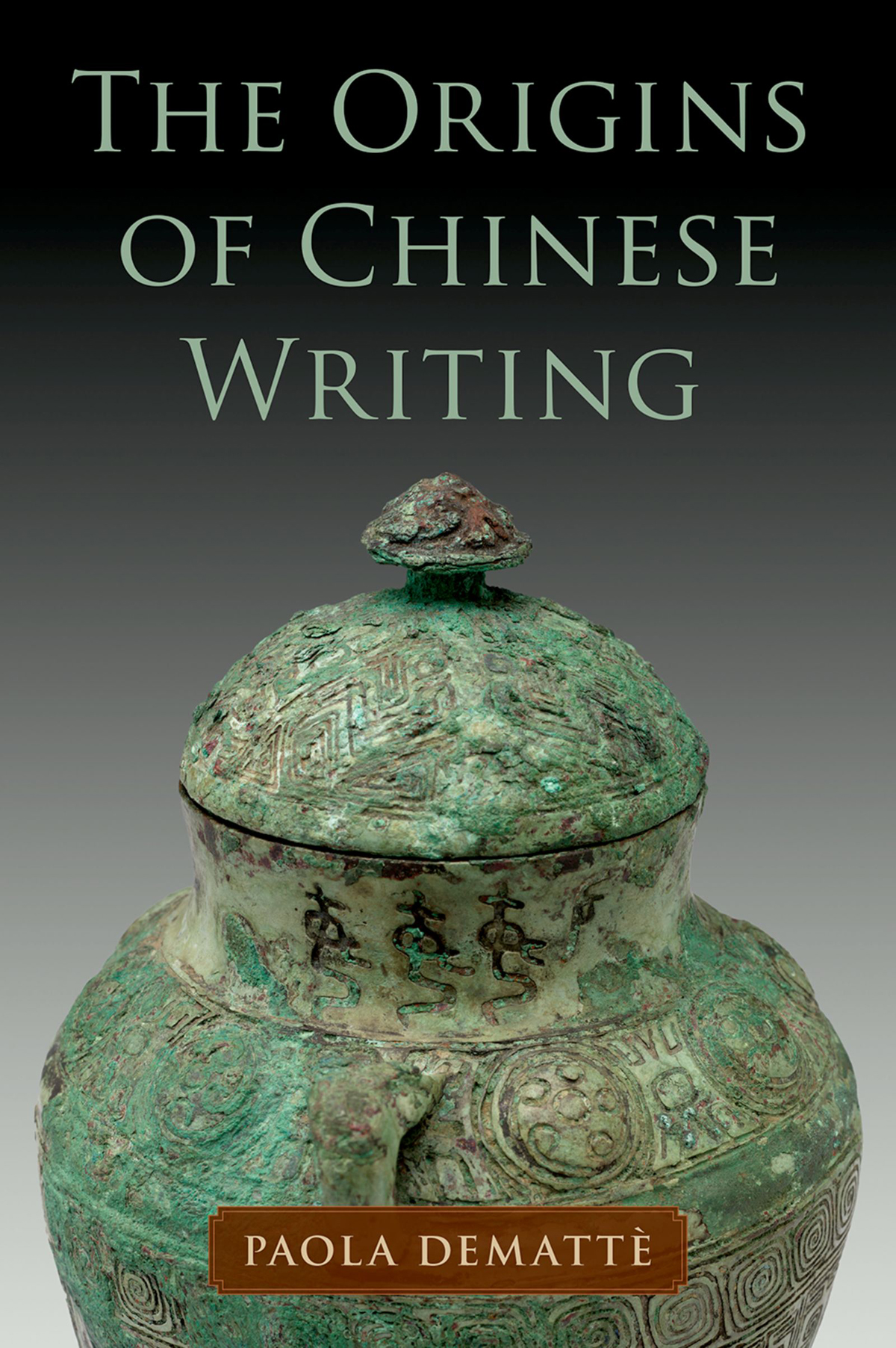

The Origins of Chinese Writing

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780197635766

eISBN 9780197635780

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197635766.001.0001

A Sandra Crescimanno, che voleva scoprire la dinastia Xia

Ai miei genitori, Silvana Giacomini e Mario Dematt

A mio marito, Richard G. Lesure

Contents

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Many people have helped me achieve the end of this research and writing project. First of all, my husband, Richard Lesure, who did not type my manuscript but like a dutiful wife listened to me ramble about Chinese writing for twenty years while cooking meals and baking desserts (which he mostly ate himself). I am extremely grateful to all my teachers and colleagues: my advisor Professor Hung-hsiang Chou, who in a Taoist manner introduced me to Chinese paleography while I was studying at UCLA; the late Professor Gao Ming who shared his immense knowledge of Chinese characters; Professor Bernard Frischer who brought me to UCLA from Italy; Professors Richard Strassberg and Li Min who have guided my research and are dear friends; Professor Giorgio Buccellati who taught me about archaeology and writing in the ancient Near East; Professors Liz Carter and Antonio Loprieno who supported me at the beginning of my academic career; Professor Guo Jue who carefully read the manuscript and provided many invaluable suggestions; and Professor Charles (Chip) Stanish who reined in an academic bully. Last but not least, I would like to remember the late Professor James Tong, who several times went out of his way to help me when I was most in need. I also want to thank my colleagues and my students at the Rhode Island School of Design: they have stimulated my search for knowledge in unexpected ways. Finally, I am extremely grateful to Stefan Vranka, Phillippa Clubbs, and all the staff at Oxford University Press for making this volume possible.

I should add that there are also a few academics in my field at UCLA and beyond who have worked very hard at trying to derail my career, that of my advisor, and even that of my husband. They have been unsuccessful but they have caused considerable grief. I will not reveal their identity, because it is not worth the ink to write their names. However, I mention this here because the bullying of young researchers, women and minorities in academia is a problem that cannot be ignored. Luckily, things are starting to change.

This study investigates the prehistoric origin of Chinese writing in the context of Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeological evidence.

The earliest undisputed texts from China are Late Shang dynasty (c. 12501045 BCE) inscriptions on shell and bones (jiaguwen), mainly from the area of the last Shang capital, Yinxu (Anyang, Henan).

The presence of these grammatical elements and the ability to record aspects of a determined spoken language indicate that by 1250 BCE the Shang script was solidly in a stage that theoreticians call glottographic (but also mature or true writing). This means that graphs were unmistakably associated with words and were no longer non-linguistic visual signs.and jades from sites near Anyang and beyond (Chang Kuang-yuan 1991a; 1991b; Song Guoding 2003).

In addition, signs that share elements with Shang script have been documented on pottery, jade, and bone artifacts from Late Neolithic contexts in the Yellow and Yangzi River valleys and coastal areas (Cheung 1983; Dematt 1999, 2010; Gao Ming 1990, end 12; Cao Dingyun 2001). The wide distribution of Late Neolithic graphs, in addition to raising the issue of an earlier origin of Chinese writing, questions the theory of a single focus of origin in the middle-lower Yellow River valley, and evokes the possibility of additional foci in the Yangzi River valley and coastal areas. Archaeological remains show that in the late pre-historic period a variety of signing systems coexisted over a wide area of China and that in time these systems may have contributed to the birth of the Shang script. These early signs are associated with ritual objects (vessels, jade implements, etc.) and contexts (offering pits, altars), introducing the possibility that Chinese writing may have originated in connection with the ritual recording needs of Late Neolithic cultures.

Notwithstanding this wealth of material, the transition from Neolithic signs to Shang writing has never been fully analyzed. The objective of this volume is three-fold: (1) to adopt a non-phonocentric theoretical approach to the study of the earliest Chinese signing systems, (2) to clarify the connections existing between Neolithic and Bronze Age graphic material assessing them in the archaeological context, and (3) to situate the debate on the origin of Chinese writing in an anthropological narrative that also includes insights from the Chinese philosophical and historical tradition.

This book is informed by diverse theoretical perspectives. Some pertain specifically to contemporary grammatology and writing, others to philosophy and textual analysis, and yet others concern archaeology and anthropology. To address the issue of what writing is, and when, why, and how it develops, I employ a theory of writing that does not privilege language as a prime mover, and that focuses instead on visual systems of communication, as well as ideological and socio-economic developments as key elements that promote the eventual development of writing.

I define writing as a system of graphic signs to note and record information that in its complete expression came to record language. However, I do Therefore, although I define glottographic writing as a graphic system that records information by adopting language structure and exploiting inherent punning potentials, I believe that the graphs of primary writing systems originated from non-glottic signs (decorations, marks, and graphs on pottery; tallies and other mnemonic records; rock art) that are collectively known as proto-writing or semasiography. For this reason, in my comparative analysis of writing, I discuss Peruvian