Perditus Liber Presents

the rare

OCLC: 781555

book:

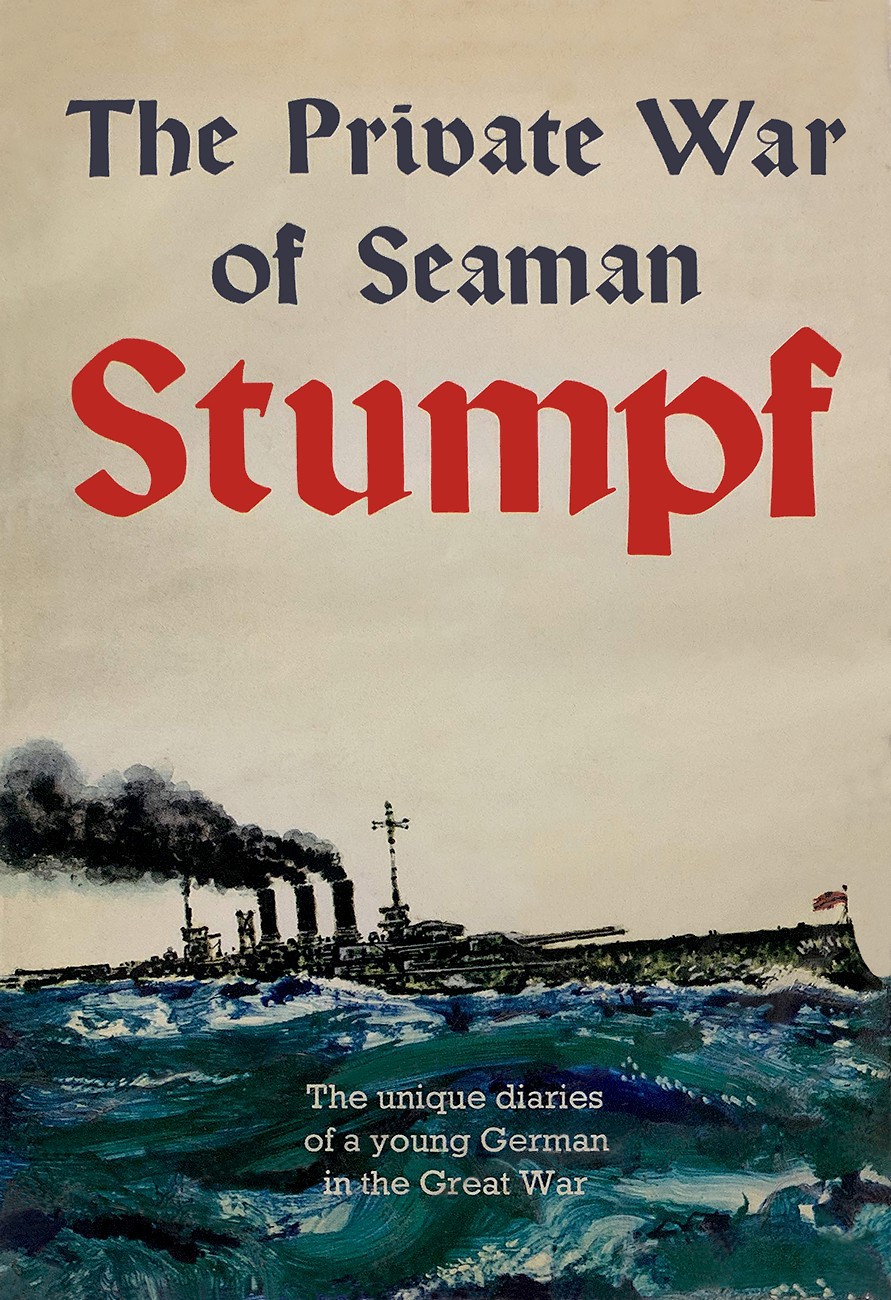

The Private War of

Seaman Stumpf

By

Richard Stumpf &

Daniel Horn

Published 1969

1967 and 1969 Rutgers, The State University

First published in Great Britain 1969 by

Leslie Frewin Publishers Limited.

15 Hays Mews, Berkeley Square. London W 1.

Printed in Great Britain by offset Litho by Taylor,

Garnett Evans & Co, Ltd, Watford, Herts and

bound by William Brendon & Son Ltd, Tiptree, Essex

09 096100 5

Preface

The text that follows is a translation of the complete version of the diary of Seaman Richard Stumpf originally entitled Memories of the German-English Naval War on H.M.S. Helgoland, as recorded in six thick notebooks of manuscript and published as Volume X, Part 2 of Das Werk des Untersuchungsausschusses der Verfassungsgebenden Deutschen Nationalversammlung und des Deutschen Reichstages 1919-1928, Vierte Reihe, Die Ursachen des Deutschen Zusammenbruches. Zweite Abteilung. Der Innere Zusammenbruch.

Since this version of the diary published by the Reichstag Investigating Committee omitted, for fear of libel suits, names of persons who were not outstanding historical personalities, I have, wherever possible, restored the names originally listed, including them in the text in brackets.

I have attempted to preserve the integrity of Stumpfs style by adhering as closely as possible to the authors sentence structure and vocabulary.

For the sake of authenticity, -occasional technical errors in the designation of ship types and the rank of officers have been retained.

There is some variation in the opening of the various books of the diary. Stumpf prepared an abbreviated index of the contents of Book I which appears at the beginning of that section. For the other books he simply included a notation of the dates of his entries.

For reading the manuscript and making many helpful suggestions I am indebted to Professor Ralph Haswell Lutz of Stanford University and the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace. I am also grateful to the Rutgers University Research Council for its financial support of this project and to Mrs. Roberta Weber, my departmental secretary, for her patience and accuracy.

For permission to use the illustrations included in this edition, I wish to thank the Militrgeschichtliches Forschungsamt in Freiburg im Breisgau and the Ullstein Bildarchiv in Berlin.

DANIEL HORN

New Brunswick, New Jersey

June, 1967.

Contents

Introduction

W hile I was engaged in research on my book on the German naval mutinies of World War I, I came across the war diary of Richard Stumpf. The diary of this ordinary seaman who served in Germanys High Seas Fleet on the battleship Helgoland was part of the interminably long and arid proceedings of the Reichstag Investigating Committee, which from 1919 to 1928 debated the causes of Germanys defeat and subsequent collapse during World War I. At first I was somewhat surprised to find such a personal document among the acrimonious, partisan, and polemical debates of that committee. However, when I had finished reading the diary and had an opportunity to compare it with the literature dealing with Germany during the war, I came to realize why the committee had accorded the Stumpf diary the distinction of being the only memoir to be published in its minutes.

Who was Richard Stumpf? Very little is known of his personal history. We do know that he was born in 1892, that he was a tinsmith by trade, that he was an ardent Catholic and belonged to a Christian trade union, and that he was quite nationalistic and conservative in his political orientation. Stumpf enlisted in the German navy in 1912 and served on the Helgoland as an ordinary seaman for six years. In 1918 he was transferred to the Wittelsbach and the Lothringen and was discharged from the navy in November. On a superficial level one might well regard Stumpf as a completely undistinguished person, no different from the thousands of other enlisted men who served in the German navy.

Actually, however, Stumpf was a highly unusual sailor. Although he did not possess much formal education, he was surprisingly well read, extremely well informed, and had seen something of the world. He knew his Goethe, Heine, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche. Somehow or other he had also acquired a smattering of Latin which permitted him to interject an occasional classical quotation in his writings. Above all, however, Stumpf knew a great deal of history. He was thoroughly familiar with German history and, even more surprising for a member of the proletariat, he was equally knowledgeable about such historical developments as the French Revolution, the Russo-Japanese War, British colonial policy, the modernization of Turkey, and the Franco-Prussian War. As a wandering journeyman, Stumpf had spent a year traveling and working in the Tyrol, had kept his eyes open and learned a great deal about the intricacies of the Austro-Hungarian Empires nationality problem and Italian-Austrian relations.

Moreover, even during the war he strove valiantly and at considerable expense to continue his education. He bought such books as Friedrich Naumanns Mitteleuropa, frequented the public reading rooms ashore, attended the theater, taught himself

Das Werk des Untersuchungsausschusses der Verjassungsgebenden Deutschen Nationalversawmilung und des Deutschen Reichstages 19191928. Vierte Reihe. Die Ursachen des Deutschen Zusanrmenbruches. Z/weite Abteilung. Der Innere Zusammenbruch . 12 Vols. Vol. X/i, pp. 43ff. Hereafter cited as Das Werk des Untersuchungsausschusses.

stenography, and worked mathematical problems. In order to keep himself informed of the political and military developments of the war Stumpf became an avid but critical newspaper reader, closely followed the Reichstag debates, and maintained a general interest in happenings in all the belligerent countries. In short, despite his apparent obscurity and lack of formal education, Stumpf was an exceptional sailor, a perceptive observer, a shrewd political analyst, and an astute critic. Consequently he was well prepared to write a meaningful diary.

Endowed with far greater historical sensitivity than other enlisted men in Germanys armed forces, Stumpf realized shortly before the outbreak of the war that events of momentous significance were about to occur and therefore began writing a diary. During four long years of war, from its outbreak in August of 1914 to the collapse of the German Empire in November 1918, he recorded his experiences, his impressions and observations. Although he intended to write only a purely personal diary, Stumpf was keenly aware of what was happening around him in the navy, on the battlefields, on the diplomatic front, and in the minds of the German people.

Stumpf kept his diary, ultimately comprising six thick notebooks, solely for himself, in order to preserve the memory of the war and to while away the long hours. As far as he was concerned, it was not addressed to any audience; it served no political purpose. As a result, he failed for some time to realize the potential importance and significance of his work. Thus, although the German navy was convulsed by two mutinies, an abortive one in the summer of 1917 and one in November 1918 which led to the outbreak of the German Revolution, although Stumpf witnessed both and participated to a limited extent in the latter, although Germany collapsed and a revolution swept away many of her old political institutions and his beloved Kaiser, Stumpf made no attempt to bring his diary to the attention of the public. At the conclusion of the war he simply left the service, returned to his former trade, moved to Nuremberg, and resumed a normal and obscure civilian existence.