Beware the toils of war... the mesh of the huge

dragnet sweeping up the world.

Alas! I hoped, the toils of war oercome, to

meet soft quiet and repose at home.

Homer, The Odyssey

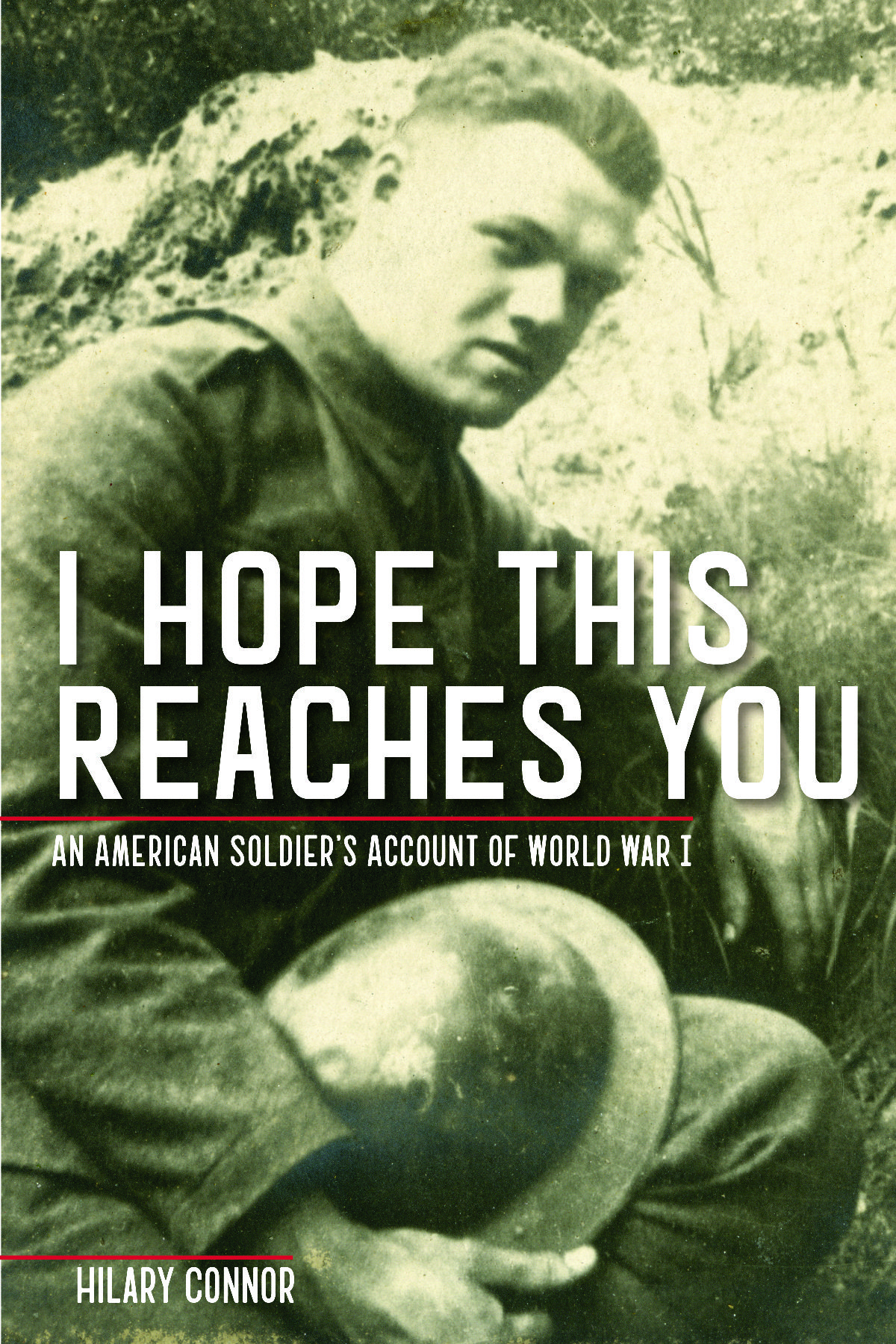

The story of men at war is a timeless saga that is shared by every soldier who has marched off to war. It is a journey seldom understood by those who have never had to take that pathto know it one has to experience it. And therein lies the trap. War is a tragedy in two parts. Surviving it is but the first act. Being able to ever fully return from it presents a far more complicated ordeal. No soldiers story is complete without recounting both. This book is dedicated to all who have gone into harms way in service of country.

Contents

Elizabeth Field Connor

The basement of my fathers house was thick with the smell of must. It was also filled with a lifetimes worth of clutter. My father had been dead for several years, yet one aspect of his life remained the samewhenever it poured, rainwater continued to seep through cracks in the cellar walls, pooling on the concrete floor beneath all of the things he had left in his wake.

Over the years, my stepmother had talked wistfully about wanting to wade into that morass to try to get a grip on what was down there, and then throw some of it out. And over the years, just as hopefully, I had agreed to help.

Finally, in the spring of 2011, I made good on that promise. After escorting my stepmother to a matinee performance of War Horse on Broadway, my husband Hilary and I returned to their house in New Jersey, where the three of us rolled up our sleeves and got to work, digging into the past. Buried in a corner was a heavy wooden box that my husband uncovered and dragged into the light.

Whats that? I asked.

My stepmother shook her head slowly, indicating she had never seen it before. Remnants of two faded shipping labels didnt offer any clues.

Looks like an army footlocker, my husband said, eyeing the stenciled lettering on the trunks olive green top. Above the black silhouette of a caduceus, the trunk was marked:

BYRON F FIELD

1st AMB. CO. MICH.

117th Sanitary Train

42nd Division

Your father never mentioned anything about an army footlocker, my stepmother said doubtfully.

My father, Byron Fiske Field Jr., had served in the Army Air Corps in World War II as the navigator of a B-25. After being shot down by a Japanese Zero, his plane crash-landed in Russia. Hed been lucky and survived with only minor injuries. Others in the plane werent as fortunate. His ordeal was far from over, thoughbecause of Russias neutrality with Japan, my father spent the remainder of the war in a Siberian camp of internment.

Other than those brief facts, hed never talked much about the war. Most vets didnt. But something told me this footlocker didnt contain my fathers story.

Lets see whats inside, my husband suggested.

An old brass lock was fastened to a metal hasp that secured the lid of the trunk. It looked formidable. Hilary gave it a tug anyway, and unexpectedly it wobbled. Apparently, someone else hadnt had a key either, and so had popped the latch pin to free the lid. But that was long ago. Now a thick growth of dust webs sealed the crack beneath the lid. I watched expectantly as my husband slipped his fingertips into the crack. The hinges creaked as the trunk opened. In the dim light, we leaned in. Immediately, I jerked my head back. The odor of mildew was overwhelming.

But the wonder that confronted me was truly staggering. Like a necromancers spell, it reached out and grabbed me. Taking a deep breath, I moved closerand found myself staring at a trove of artifacts layered up to the lip of the trunk. What I saw brought me to my knees.

I tried not to breathe too deeply as I began to sort through the carefully organized sections. Items stacked on the bottom were contaminated by mold from moisture that had seeped into the trunk each time the basement had flooded. Fortunately, most of what was packed away was still high and dry. Treasuresranging from the yellowed pages of a diary kept by my grandfather during World War I to sepia-tinged photographs and daguerreotype pictures of distant relativeswere pure gold to my eyes.

Suddenly, the risk of inhaling mold spores no longer seemed important. Instead, my focus was on breathing new life into the past as I tried to divine the meaning and purpose of each artifact that I extracted from the trunk. Hundreds of picture postcards of villages in France and Germany were meticulously maintained in a card file. Dozens of war letters, written to a woman whose name I didnt recognize, were neatly tied in bundles. Four books on the Great War and high school and college yearbooks from the early 1900s were brittle to the touch but otherwise still intact. A copy of the New Testament given to my grandfather at the age of seven and a family Bible from 1888 had been reverentially packed away for safekeeping. A family photo album, songbooks, reams of piano sheet music, Masonic Temple aprons, and other bits and pieces of my grandfathers life were sprinkled here and there like jewels in a treasure chest.

After taking stock of the items, I stood up, still clutching a framed photograph of my grandfather taken somewhere in the trenches of France. I studied the young faceeyes old beyond their years stared back.

It was a lot to absorb in one sitting. Yet a portrait had begun to emergeof an articulate and promising young man who, like thousands of other patriotic Americans, had set aside his hopes and dreams to answer his countrys call to duty by enlisting and fighting in the war to end all warsWorld War I. Growing up in the Midwest, Id never gotten to know that man. My grandfather had visited occasionally but mostly hed lived on the West Coasta distant and mysterious figure in the eyes of a small child. Id been told that he was an exceptionally intelligent man but had suffered recurring bouts of alcoholism that cost him prestigious jobs in private industry and universities, eventually ruining his marriage and straining his relationship with his son and daughter.

At the age of seventy, he died alone in a Veterans Administration hospital in San Francisco. A letter I had written to him when he was hospitalized there was among the keepsakes I found in the trunk. In that letter, dated December 13, 1967, I told him how sorry I was to hear that he was ill. Then, hoping to cheer him up, I asked him what hed like for Christmas. He never replied. Seven weeks later he died.