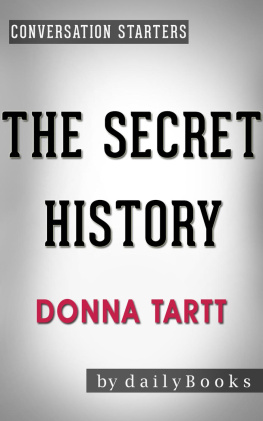

DonnaTartt

TheSecret History

For Bret Easton Ellis, whose generosity will never ceaseto warm my heart; and for Paul Edward Mc Gloin, muse and Maecenas, who is thedearest friend I will ever have in this world.

I enquire now as to the genesis of a philologist and assertthe following:

1. A young man cannot possibly know what Greeks and Romansare.

2. He does not know whether he is suited for finding out aboutthem.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE, Unzeitgemdsse Betrachtungen

Come then, and let us pass a leisure hour in storytelling, andour story shall be the education of our heroes.

PLATO, Republic, book ii

Prologue

The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had beendead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of oursituation. He'd been dead for ten days before they found him, you know. It wasone of the biggest manhunts in Vermont history state troopers, the FBI, evenan army helicopter; the college closed, the dye factory in Hampden shut down,people coming from New Hampshire, upstate New York, as far away as Boston.

It is difficult to believe that Henry's modest plan couldhave worked so well despite these unforeseen events. We hadn't intended to hidethe body where it couldn't be found. In fact, we hadn't hidden it at all buthad simply left it where it fell in hopes that some luckless passer-bywould stumble over it before anyone even noticed he was missing. This was atale that told itself simply and well: the loose rocks, the body at the bottomof the ravine with a clean break in the neck, and the muddy skidmarks of dug-inheels pointing the way down; a hiking accident, no more, no less, and it mighthave been left at that, at quiet tears and a small funeral, had it not been forthe snow that fell that night; it covered him without a trace, and ten dayslater, when the thaw finally came, the state troopers and the FBI and thesearchers from the town all saw that they had been walking back and forth overhis body until the snow above it was packed down like ice.

It is difficult to believe that such an uproar took placeover an act for which I was partially responsible, even more difficult tobelieve I could have walked through it the cameras, the uniforms, the blackcrowds sprinkled over Mount Cataract like ants in a sugar bowl withoutincurring a blink of suspicion. But walking through it all was one thing;walking away, unfortunately, has proved to be quite another, and though once Ithought I had left that ravine forever on an April afternoon long ago, now I amnot so sure. Now the searchers have departed, and life has grown quiet aroundme, I have come to realize that while for years I might have imagined myself tobe somewhere else, in reality I have been there all the time: up at the top bythe muddy wheel-ruts in the new grass, where the sky is dark over theshivering apple blossoms and the first chill of the snow that will fall thatnight is already in the air.

What are you doing up here? said Bunny, surprised, when hefound the four of us waiting for him.

Why, looking for new ferns, said Henry.

And after we stood whispering in the underbrush one lastlook at the body and a last look round, no dropped keys, lost glasses,everybody got everything? and then started single file through the woods, Itook one glance back through the saplings that leapt to close the path behindme. Though I remember the walk back and the first lonely flakes of snow thatcame drifting through the pines, remember piling gratefully into the car andstarting down the road like a family on vacation, with Henry driving clench-jawedthrough the potholes and the rest of us leaning over the seats and talking likechildren, though I remember only too well the long terrible night that layahead and the long terrible days and nights that followed, I have only toglance over my shoulder for all those years to drop away and I see it behind meagain, the ravine, rising all green and black through the saplings, a picturethat will never leave me.

I suppose at one time in my life I might have had any numberof stories, but now there is no other. This is the only story I will ever beable to tell.

Book

Chapter

Does such a thing as 'the fatal flaw,' that showy dark crackrunning down the middle of a life, exist outside literature? I used to think itdidn't. Now I think it does. And I think that mine is this: a morbid longingfor the picturesque at all costs.

A moi. L'histoire d'une de mes folies.

My name is Richard Papen. I am twenty-eight years oldand I had never seen New England or Hampden College until I was nineteen. I ama Californian by birth and also, I have recently discovered, by nature. Thelast is something I admit only now, after the fact. Not that it matters.

I grew up in Piano, a small silicon village in the north. Nosisters, no brothers. My father ran a gas station and my mother stayed at homeuntil I got older and times got tighter and she went to work, answering phonesin the office of one of the big chip factories outside San Jose.

Piano. The word conjures up drive-ins, tract homes,waves of heat rising from the blacktop. My years there created for me anexpendable past, disposable as a plastic cup. Which I suppose was a very greatgift, in a way. On leaving home I was able to fabricate a new and far moresatisfying history, full of striking, simplistic environmental influences; acolorful past, easily accessible to strangers.

The dazzle of this fictive childhood full of swimmingpools and orange groves and dissolute, charming show-biz parents has allbut eclipsed the drab original. In fact, when I think about my real childhood Iam unable to recall much about it at all except a sad jumble of objects: thesneakers 1 wore year-round; coloring books and comics from thesupermarket; little of interest, less of beauty. I was quiet, tall for my age,prone to freckles. I didn't have many friends but whether this was due tochoice or circumstance I do not now know.1 did well in school, it seems, butnot exceptionally well; I liked to read Tom Swift, the Tolkien books butalso to watch television, which I did plenty of, lying on the carpet of ourempty living room in the long dull afternoons after school.

I honestly can't remember much else about those years excepta certain mood that permeated most of them, a melancholy feeling that Iassociate with watching 'The Wonderful World of Disney' on Sunday nights.Sunday was a sad day early to bed, school the next morning, I was constantlyworried my homework was wrong but as I watched the fireworks go off in thenight sky, over the floodlit castles of Disneyland, I was consumed by a moregeneral sense of dread, of imprisonment within the dreary round of school andhome: circumstances which, to me at least, presented sound empirical argumentfor gloom. My father was mean, and our house ugly, and my mother didn't paymuch attention to me; my clothes were cheap and my haircut too short and no oneat school seemed to like me that much; and since all this had been true for aslong as I could remember, I felt things would doubtless continue in thisdepressing vein as far as I could foresee. In short: I felt my existence wastainted, in some subtle but essential way.

I suppose it's not odd, then, that I have troublereconciling my life to those of my friends, or at least to their lives as Iperceive them to be. Charles and Camilla are orphans (how I longed to be anorphan when I was a child!) reared by grandmothers and great-aunts in ahouse in Virginia: a childhood I like to think about, with horses and riversand sweet-gum trees. And Francis.

His mother, when she had him, was only seventeen athinblooded, capricious girl with red hair and a rich daddy, who ran off withthe drummer for Vance Vane and his Musical Swains.

She was home in three weeks, and the marriage was annulledin six; and, as Francis is fond of saying, the grandparents brought them uplike brother and sister, him and his mother, brought them up in such amagnanimous style that even the gossips were impressed English nannies andprivate schools, summers in Switzerland, winters in France. Consider even bluffold Bunny, if you would. Not a childhood of reefer coats and dancing lessons,any more than mine was. But an American childhood. Son of a Clemson footballstar turned banker. Four brothers, no sisters, in a big noisy house in thesuburbs, with sailboats and tennis rackets and golden retrievers; summers onCape Cod, boarding schools near Boston and tailgate picnics during footballseason; an upbringing vitally present in Bunny in every respect, from the wayhe shook your hand to the way he told a joke.

Next page