CONTENTS

The opinions of current and former members of the Australian Defence Force expressed in this book are their own and do not represent the opinions of the Australian Defence Force.

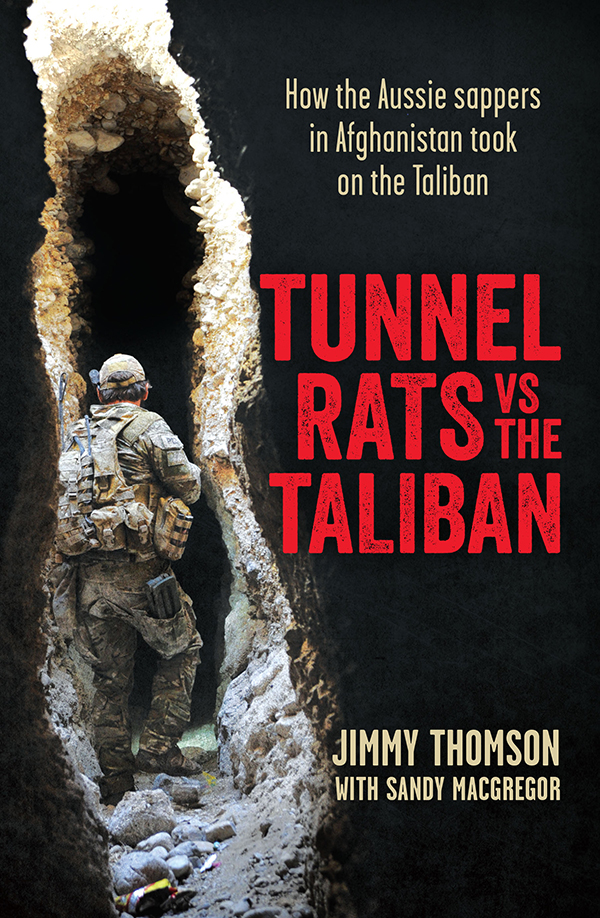

Before the Soviet Union quit Afghanistan in 1989, theylike Australian and American troops who followed fifteen years latertried to train the Afghan army to fight its own battles against rebels and insurgents. They failed. In fact, the only enduring legacy they left behindapart from radicalised Muslim minorities and battle-hardened Mujaheddin fighterswas between ten and fifteen million landmines.

The Mujaheddin had been waging a guerrilla war of hit and run, so the Russians became highly dependent on secured minefields. Mines were laid not as booby traps, but as a deterrent to prevent enemy troops getting too close to their bases. These were mainly anti-personnel mines and the minefields were clearly marked. Unlike Vietnams Barrier Minefield, the Russians guarded their minefields fairly effectively so there was little recycling of their mines for use against the people who had planted them.

Later, as the Mujaheddin got their own armoured transports, both sides began to lay anti-tank mines that were intended for use against the unwary. Add to that unexploded bombs, rockets and shells, and post-Russian Afghanistan in the 1990s was a sea of deadly devices that had killed an estimated 25,000 Afghans during the war, and threatened to continue to kill civilians in their tens of thousands if they werent dealt with. At one point, the Red Cross estimated it would take more than 4000 years to clear all the landmines left in Afghanistan.

In response to this humanitarian crisis, in 1989 the United Nations sent a peacekeeping force to neighbouring Pakistan, which is how the first Australian troops to operate in Afghanistan came to be sappers. The United Nations Mine Clearance Training Team (UNMCTT) arrived just across the border in Peshawar, Pakistan, five months after the last Soviet forces rolled out of Afghanistan.

For the next four and a half years, the UNMCTT conducted Operation Salaam, initially to train Afghan refugees in mine clearance and bomb disposal. Then in 1991, they crossed the border to help plan and supervise mine clearance in Afghanistan itself. In all, almost one hundred Australian sappers took part in the exercise, in groups of between four and nine at a time, alongside soldiers from eight other United Nations countries.

However, just one year later, only Australian and New Zealand troops were left on the ground. Then a young captain, Major Mark Willetts, was posted to Operation Salaam as a detachment commander in 1992.

I was operations officer for the seventh rotation of sappers there, Mark recalls. The fifth had been based mainly in Pakistan but the sixth had managed to get all their members across the border into Afghanistan at least once. By the time we arrived, it was routine business to go across the border.

There were about five million Afghan refugees in Pakistan at that time, and even more in Iran. But their refugee camps were like nothing Mark Willetts had ever seen before.

When we first arrived in Peshawar, we were being driven out to the house and the guys were saying, Oh, this is all refugee camp here. But I was looking out of the window at classic central Asian mud-brick construction. Just a sea of it, housing tens of thousands of people. The Afghans, and particularly the Pashtuns, wear poverty very well and they dont like living in tents. So they would start with tents but very quickly bang up walls around them, then put the roof over the top and the tents gone.

It was a refugee camp but they turned it into a suburb. It looked just like another suburb; another domicile suburb of Peshawar complete with its own bazaar where you could buy anything.

Among the things the Aussie sappers bought at the Peshawar bazaar were the same clothes that the locals wore, all the better to blend in and make their hosts realise they were all on the same side. The engineers were also able to ignore the rule that soldiers must shave every day when they have access to hot watera small fact that would have significance later when the war in Afghanistan was in full swing. The exciting thing was that we were allowed to wear coveralls and grow beards before we left, says Mark. We got pulled up all the time by RSMs [regimental sergeant majors] and sergeants when we were in barracks. The purpose of wearing beards was so that we could integrate as much as possible with the population we were working with. We wore a Pakistani army safari suit when we were on the Pakistan side and then traditional Afghan clothesthe long baggy shirt and pantson the other side. Partly it was to blend in better but also because the Australian Army camouflage gear was very similar to Russian camo gear and the locals were quite willing to take pot shots from a distance before they asked any questions.

We lived in houses in a nice suburb in Peshawar in a walled compound with locals. The previous contingents, because the 1991 Gulf War had just started, werent allowed out. They had to stay in for their protection. The sixth contingent started going out again and we just continued that.

We could go out at night. The United States government had a consular office and an employees club run by Australians so that was where we could go for a drink. Wed go running through the suburbs and, if I got the time, my Pakistani driver would take me to the old city in Peshawar. It was the classic Arabian Nights bazaar type of thing, like [the film] The Thief of Bagdad. I would wander through that at night and talk with the locals and have cups of tea and play cricket with the kids.

The original United Nations mission had been to train some of the Afghan refugees in general mine awareness and to show them how to clear areas of mines and unexploded ordnance and bombs. The previous rotation had changed from training individuals to teaching trainers so that the process could be sustained after the United Nations had pulled out.

Marks unit took that a stage further and crossed the border to make sure the trainers in Afghanistan were working effectively, that they were being managed properly and to investigate any incidents where mines or bombs had gone off. They checked the working, living and sleeping conditions of the mine clearers, right down to food and hygiene. They also checked that United Nations funds were being properly allocated and spent and observed the mine clearers working to make sure they were doing everything by the book.

We discovered early on that they would put on a bit of a show when we turned up. At training, everybody would be lined up in neat rows, lines would be painted in the dirt and they would look very impressive. Out in the minefield they would do everything exactly as theyd been told.

But when they thought they werent being watched they would take short cuts, so we started hiding on hillsides with binoculars and loudhailers. We had a translator with us, wed hand him the bullhorn and he would yell abuse across the dasht and then all these heads would pop up.

The Afghans didnt like getting their hands or their clothes dirty, so they would kneel down over the mines, rather than lying flat on the ground. Think about it. When theyre kneeling theyre more likely to have their head right over a device. If it goes off, it takes their head. But if theyre lying down, particularly working at full arms length, they wont even scratch a fingernail if the blast goes off. Theyll get a ringing in their ears but no other injuries so the injuries we got were from inappropriate technique or occasionally just fatigue mishaps.

Next page