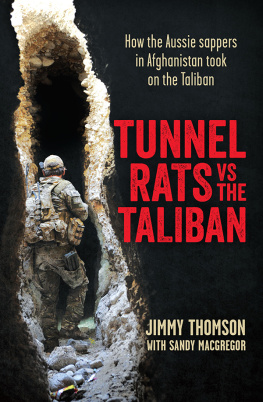

Much of the material in this book, including interviews with the men of 3 Field Troop, was originally gathered by author Jimmy Thomson for Sandy MacGregors self-published book No Need For Heroes . Sandy has since added material from his own archives and research, which has been included in this version of the story, now presented as a military history rather than a personal memoir.

First published in 2011

Copyright Jimmy Thomson and Sandy MacGregor 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 489 5

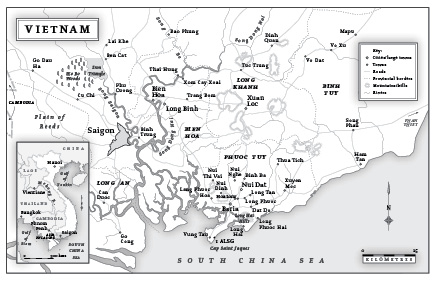

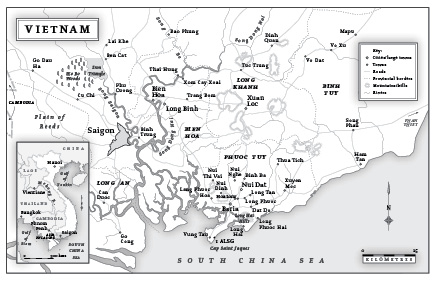

Map of Vietnam by Ian Faulkner

Set in 12/18 pt AIProsperall by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Corporal Bob Bowtell, who died in the tunnels at Ho Bo Woods, Cu Chi, South Vietnam, in January 1966. To all those soldiers who served with 3 Field Troop Royal Australian Engineers, September 1965 to September 1966, and all the Tunnel Rats, Australian and American, who followed them into the Vietcongs underground cities.

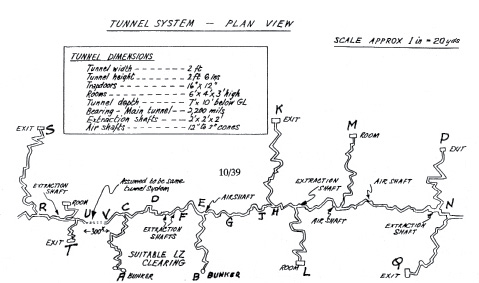

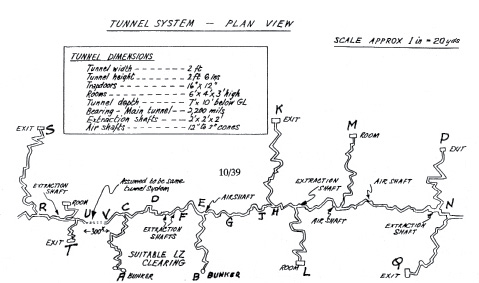

A plan of the Cu Chi Tunnels searched on Operation Crimp, January 1966. Four soldiers were killed or wounded from the enemy bunker at A. Engineers commenced their underground search from point A.

PROLOGUE

You launch yourself headfirst down a hole in the ground thats scarcely wide enough for your shoulders. After a couple of metres of slipping and wriggling straight down, the narrow tunnel takes a U-turn towards the surface, then twists again before heading off further than you can see with the battery-powered lamp attached to your cap.

Because the tunnel has recently been full of smoke and tear gas, you are wearing a gasmask. The eyepieces steam up and the sound of your own breathing competes with the thump of your heart to deafen you. You know you are not safe. You are in your enemys domain and one of your comradesa friendhas already died in a hole in the ground just like this one.

This is the stuff of nightmares: a tunnel thats almost too small to crawl along, dug by and for slightly built and wiry Vietnamese, not broad-backed Aussies or Americans.

Every inch forward has to be checked for booby traps, so you have a bayonet in one hand. Every corner could conceal an enemy soldier, perhaps one who can retreat no further, so you have a pistol in the other. Theres no room to turn around. Going forward is difficult enough; backing out is nigh impossible. You know that the enemy knows youre there. You know your miners light makes a perfect target. You switch it off. The silence is ominous, though not quite complete as the pounding of your heart throbs through your body. The velvet darkness is all-engulfing.

Then it becomes harder to catch your breath. You become light-headed, then dizzy and confused as the air runs out. Reason and sense evaporate as the darkness claims you. But you get a grip...you breathe...you bring it all back under control because the alternativeblind panicmeans death. And you move on.

Thats how it felt to be a Tunnel Rat. Thats what it was like to know real fearfear of being trapped, fear of an unseen enemy, fear of ever-present booby traps and, most of all, fear of the unknown. There was no military textbook, training class or official orders that told the diggers in 3 Field Troop who went down the Vietcongs tunnels what to expect and how to deal with it, for the very simple reason that they were the first. No Australian or American had ever explored a major tunnel system before.

On New Years Day 1966, one of the most remarkable episodes in Australian military history began with a last-minute change of plan. The engineers of the newly formed 3 Field Troop had just been helping to free six armoured personnel carriers stuck in swamps near the Cambodian border. On their way back to camp, they were diverted to an area known as Ho Bo woods, north of Saigon, which was believed to contain the Southern Command headquarters of the Vietcong and North Vietnamese army. Intense Vietcong activity supported this theory but while carpet bombing of the area and intense artillery bombardments drove the enemy troops out, they seemed to reappear again soon after.

The Americans (and Australians, New Zealanders and Koreans) knew their South Vietnamese allies HQ was riddled with Vietcong spies and assumed the Vietcong were getting advance warning of attacks, so that they could make themselves scarce. So they decided to order the launch of Operation Crimp in the fielda last-minute decision was taken to divert large numbers of troops to the area for a major search and destroy mission. It was called Crimp because the American 173rd Brigade was to go through the north of the area while the Australians of the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1 RAR) squeezed the enemy from the south.

But the day before the assault, 1 Battalion Operations Officer Major John Essex-Clark suspected, rightly, that they might be the ones caught in the jaws of a trap and demanded they switch to another landing zone. The suspiciously bare earth he had spotted in a reconnaissance flight would, indeed, turn out to be enemy defensive positions.

Even so, their hot insertiondeployment by air under covering firemet stiff resistance. The Australians were dodging bullets from the moment they hit the ground in their Huey helicopters. A signal from Saigon, warning the Vietcong that Crimp was on, was intercepted minutes before the first stick of choppers dropped onto the new landing zone.

This still didnt add up. The pounding the area had taken from artillery and air strikes should have cleared Vietcong forces before the ground troops went in. But they were still there and putting up one hell of a fight, popping up on all sides as the main wave of Aussie troops landed.

The Aussies were under constant sniper fire and skirmishes would break out as groups of Vietcong seemed to materialise out of thin air. Booby-trap bombs were going off, the diggers came under friendly fire from gunships who thought they were Vietcong, and their own artillery shells were creeping closer by the second.

It became apparent that the landing area Essex-Clark had rejected would have been in the middle of a web of Vietcong crossfire that would have cut the Aussie troops to shreds. Even so, the Vietcong still had one trump card to play. When infantrymen tried to secure the clearing originally planned to be the landing zone, they discovered it was well defended with booby-trap bombs and spikes. When a couple of soldiers came under fire they dived into a washed-out gully beside a track and were shot at close range. Again, this didnt make sense. The area had been cleared and there shouldnt have been any enemy troops within range. When two medics crawled in to help the wounded, they too were both shot and killed.