BATTLE DIGEST

Lessons for Todays Leaders Volume 1 * Issue 8

Early American Wars:

New Orleans

Date

January 8, 1815

LOCATION:

New Orleans, Louisiana

OPPOSING FORCES

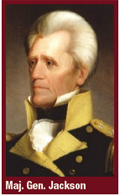

American: 5,700 regular and militia troops commanded by Brevet Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson. Key subordinates included Brig. Gen. David Morgan commanding 1,076 men on the West Bank of the Mississippi, and U.S. Navy Commodore Daniel Patterson supporting Jackson with two ships (USS Carolina and USS Louisiana ).

British: 8,000 troops commanded by Maj. Gen. Sir Edward Pakenham. Key subordinates included Maj. Gens. Sir John Keane, Sir John Lambert, and Sir Samuel Gibbs. (Adm. Sir Alexander Cochrane was the expeditions overall commander but took little part in the ground campaign.)

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The War of 1812 had not gone particularly well for the United States. The British were blockading Americas coasts, damaging commerce, and thwarting any hopes for U.S. territorial gains in Canada. After two years of fighting, Americans were further humiliated when, in August of 1814, the British burned the U.S. Capitol. The people in the young republic yearned for respect. Brevet Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson would finally give them that respect with his lopsided victory at New Orleans. Although the War of 1812 officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent two weeks prior to the battle, the commanders on the ground were unaware of it at the time. Ironically, because news of Jacksons victory reached Washington so closely timed with word of the peace treaty, New Orleans would long be etched in the American conscience as the victory that ended the war. More accurately, the war was a draw. Nevertheless, the victory at New Orleans was significant enough for the U.S. to earn the respect of Britain, which never again treated America as anything less than an independent power. It would also launch the political career of a future president.

STRATEGY & MANEUVER

Actions by the Americans Britains heavy-handed attempts to cut off supplies to Napoleon in Europe had been pushing America toward war for years. Not only had shipping and commerce been disrupted, but since 1807 when a British warship attacked the USS Chesapeake , American sailors had been pressed into service of the Crown. President Thomas Jefferson took the drastic step of halting all trade with England, but popular outrage continued to grow. Things reached a breaking point on 18 June 1812, when the Senate approved President James Madisons request for a declaration of war against Great Britain.

Initially, American strategy focused on invading Canada and securing the Northwest Territory. But by 1814, after two years of lackluster results and increasing British aggressiveness, U.S. strategy turned more defensive. For the first two years of the war, British forces had not been active in the American South. Jackson was occupied against the Spanish in Florida and against the Creek Indians in the Mississippi Territory.

His victory at Horseshoe Bend in March 1814 effectively ended the Creek War and propelled his appointment as a Maj. Gen. in the Regular Army. In May that year, Jackson assumed command of the 7th Military District, which included New Orleans. When he learned of Britains upcoming campaign in the Gulf, he suspected Adm. Sir Alexander Cochrane might use an overland route to take New Orleans. Working quickly, Jackson helped thwart the initial British attack at Fort Bowyer, near Mobile. He then moved his forces to New Orleans.

When Jackson arrived on 1 December, he found the defenses in poor condition. After assembling his uniquely American army comprised of Regulars, militia, two brigades of New Orleans free black men, Choctaw Indians, and even Jean Lafittes 800 pirates, he threw himself into preparing for the coming fight. A few weeks later, on 23 December, Jackson received surprising news from his scouts. A British force had already landed and was encamped just nine miles southeast, at Viller Plantation in Chalmette, Louisiana. By the Eternal, Jackson roared, they shall not sleep on our soil! He decided to attack.

Actions by the British Britain found itself in another war with America, but her forces were heavily committed against Napoleon in Europe. This forced a strategy focused on protecting Canada from American territorial designs, while trying to weaken American resolve by crippling her commerce. Things changed with Napoleons defeat in 1814. As Britain was able to shift more resources to America, her strategy became more punishing. Blockades were tightened and ground troops conducted more extensive coastal raids. After the successful raids in Maryland, including the burning of the U.S. Capitol, Britain turned her attention to the Gulf of Mexico.

Because of New Orleans geographical and commercial importance, Cochrane, who had led operations in the Chesapeake Bay, wanted to capture or destroy the city and complicate American control of the region and the vital Mississippi River. Initially, he planned an indirect approach, landing at Mobile Bay and marching overland to the Mississippi River and down to New Orleans. But after the force he sent to attack Mobile was repulsed in September 1814, he changed his plan.

Cochrane planned to rendezvous with fresh troops in Jamaica and sail to the Gulf Coast before the end of 1814. With Maj. Gen. Robert Rosss death at the Battle of North Point near Baltimore, Maj. Gen. Sir Edward Pakenham was offered command. But because Pakenham had to sail from England, Maj. Gen. Sir John Keane led the force when they departed Jamaica on 26 November. Once Cochranes fleet defeated the American gunboat flotilla defending Lake Borgne on 14 December, the path was clear. Keanes men rowed ashore, and by the 23rd, they had made camp nine miles southeast of New Orleans at the Viller Plantation, and awaited reinforcements. (Map 1)

TACTICS OF THE BATTLE

The Battle of New Orleans was the last of four separate engagements between the two forces over the span of two weeks. In this final twohour assault, the British conducted a frontal attack against Jacksons well-prepared defenses just south of the city. It ended in a rout of the British.

23 December 1814 (Jacksons spoiling attack) After Jacksons scouts found the British camp, they estimated the British strength between 1,600 and 1,800 men. Knowing this wasnt Cochranes full force, Jackson chose to strike before they could assemble. That evening, he led 2,100 of his men southeast in a surprise attack.

In the early evening darkness, the USS Carolina drifted into position. British sentries near the river saw the ship and assumed it was a British supply vessel. When they hailed the ship, it let loose a deafening volley of grapeshot into the nearby British camp. Confusion swept through British ranks.

Keane hesitated until Lt. Col. Sir William Thornton, of the 85th Regiment of Foot, took over and organized a counterattack. The British were unsure where the attack was coming from until American troops, wheeling two cannons, burst out of the woods. The suddenness of the attack had pushed the British regiments back, but after reforming, Thornton led a force to capture the American guns. Jackson quickly countered, rallying his men to retake them. Both sides then traded volleys in the dark, smoke-covered field until the fighting became hopelessly confused. At that point, Jackson ordered a withdrawal. American casualties were 213 with the British suffering 277.