This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 2009 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

COMMAND AND CONTROL OF THE U.S. TENTH ARMY DURING THE BATTLE OF OKINAWA

By

Major Paul E. Cunningham II.

ABSTRACT

From 1 April 1945 to 21 June 1945, the United States Tenth Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Simon B. Buckner, Jr., executed Operation Iceberg--the seizure of Okinawa for use as a staging base for the expected invasion of Japan. The Tenth Army, which included the U.S. Armys XXIV Corps and the U.S. Marines Corps III Amphibious Corps, executed an amphibious assault on Okinawa against the Japanese 32nd Army. The Japanese defenders allowed the Tenth Army to land virtually unopposed, preferring to fight a battle of attrition from strong fortifications. The Tenth Army rapidly seized the lightly defended northern end of the island, but became quickly bogged down against the main Japanese defensive belt on southern Okinawa. Japanese air power repeatedly assaulted the supporting Allied naval force with massed kamikaze attacks, resulting in heavy casualties. Ultimately, Lt. Gen. Buckner committed both corps to a frontal attack on the Japanese defenses in southern Okinawa and the campaign lasted some eighty two days before the final collapse of the 32nd Army. This thesis examines the effectiveness of Buckner and his staffs command and control of the Tenth Army. Buckner and his staff succeeded, but flaws in Buckners generalship and his staffs failure to provide him with an accurate battlefield picture prolonged the campaign.

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

Large military operations are complex, multi-layered undertakings in which groups of men and equipment collide in the violent pursuit of tactical, operational, and strategic objectives. No human endeavor imposes a greater burden upon leaders, whose actions dictate success and failure, life and death. Military leaders direct their troops in battle through the exercise of command and control. This thesis examines one such leader, Lieutenant General Simon B. Bolivar Buckner, Jr., and his staff, exploring their successes and shortcomings in the command and control of the United States Tenth Army during the Battle of Okinawa.

Prelude to Iceberg

The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 drew the United States into war against the Japanese Empire. The Japanese scored numerous early victories in the war, including the invasion and occupation of the Philippines and the capture of Attu and Kiska in Alaskas Aleutian Island chain. However, after the American victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, the tide had turned against the Japanese. The Allies, backed by the weight of the United States fully mobilized industrial capacity, began an inexorable march toward Japan.

In late September 1944, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Ocean Areas, met with the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest King, in San Francisco to discuss the next moves in the war against the Japanese Empire. Admiral King favored the invasion of Formosa as a prelude to the ultimate assault upon the Japanese home islands. Nimitz held a different position. After consulting with his staff and senior commanders, Nimitz had concluded that an invasion of Formosa was not feasible due to resource limitations and the Japanese strength on the island. Nimitz made his case to King, recommending the seizure of Iwo Jima, followed by the invasion of Okinawa, in the Ryukyus Islands. Nimitz believed that, if the main purpose of the Formosa operation was to acquire air bases from which to bomb Japan, that it could be achieved at a lower cost in men and resources by capturing positions in the Ryukyus. {1} The Ryukyus offered a naval anchorage at Okinawa and were within medium bomber range of Japan, with planners estimating that seven hundred eighty bombers and the necessary number of fighters could be based there. {2} Nimitz outlined his arguments convincingly, swaying King to his point of view.

King subsequently recommended to the Joint Chiefs of Staff the adoption of Nimitzs course of action, in conjunction with the invasion of the Philippines by General Douglas MacArthurs Southwest Pacific Area forces. On October 3, 1944, the Joint Chiefs ordered Nimitz to seize Iwo Jima and Okinawa. The projected Okinawa campaign, along with the Philippines and Iwo Jima operations, were calculated to maintain unremitting pressure against Japan and to effect the attrition of its military forces. {3} The operation to invade Okinawa received the codename, Iceberg.

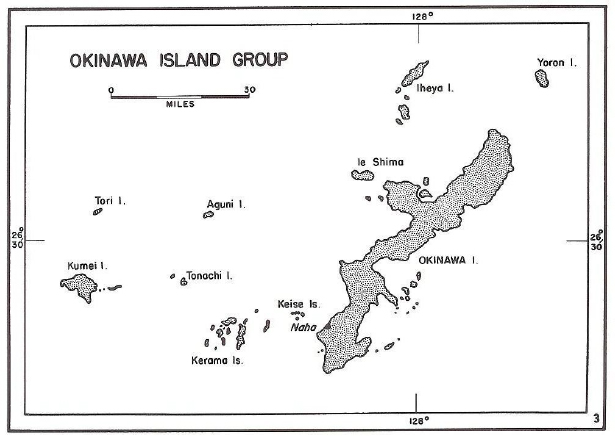

The Ryukyus and Okinawa

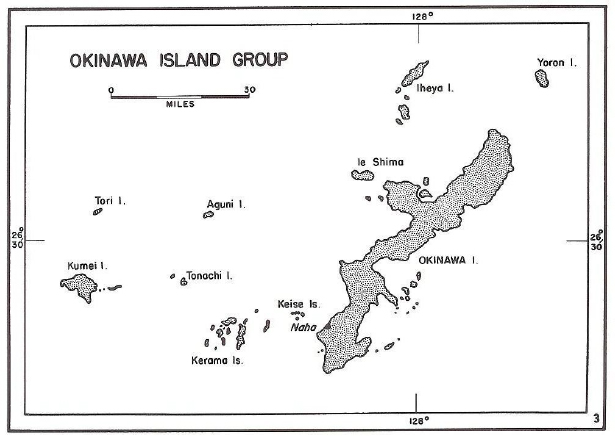

The Okinawa group of approximately fifty islands is part of the Ryukyus Islands archipelago, located southwest of Japan and northeast of Formosa and the Philippines. The main island of Okinawa lies less than four hundred nautical miles from the Japanese home islands. The main island is surrounded by smaller islands, including the Kerama Islands and Ie Shima. The island of Okinawa is approximately sixty miles long and has a maximum width of eighteen miles. At the Ishikawa Isthmus, which separates the island into two distinct regions, Okinawa is only two miles wide. North of the isthmus, approximately two thirds of the islands total area, the terrain is mountainous and heavily wooded, with peaks rising up to fifteen hundred feet. Below the isthmus, the terrain features mostly rolling, lightly wooded country, broken by ridges and ravines. The peaks in the south rarely exceed five hundred feet, rising above mostly arable land. Okinawas tropical climate is characterized by hot summers, moderate winters, high humidity, and heavy annual precipitation, with the heaviest rains occurring from May through September.

Figure 1. The Okinawa Island Group

Source : Roy A. Appleman, et al, Okinawa: The Last Battle (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1948), 6.

In 1940, Okinawa had a population of nearly five hundred thousand people. {4} Most of the people lived on the southern third of the island and led an agrarian existence. The two largest cities, both located in the south, were Shuri and Naha. As a prefecture of Japan, Okinawa fell firmly under Japanese control. Although the Japanese dominated the island, applying a thin veneer of Japanese culture to the natives, the Okinawans retained their own culture, religion, and form of ancestor worship, characterized by the lyre-shaped tombs dotting the countryside. {5} The Japanese citizens residing on Okinawa kept the native islanders in a position of inferiority, spawning resentment amongst the Okinawans. The Japanese government also imposed mandatory military service on Okinawan men.