2012 by the University of New Mexico Press

All rights reserved. Published 2012

Printed in the United States of America

16 15 14 13 12 1 2 3 4 5

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS

FOLLOWS:

Yetman, David, 1941

Conflict in colonial Sonora : Indians, priests, and settlers / David Yetman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8263-5220-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8263-5222-4 (electronic)

1. Indians of MexicoMissionsMexicoSonora (State)

2. Indians of MexicoMexicoSonora (State)HistorySources.

3. Indians of MexicoMexicoSonora (State)Social conditions.

4. JesuitsMissionsMexicoSonora (State)HistorySources.

5. Frontier and pioneer lifeMexicoSonoroa (State)HistorySources.

6. Sonora (Mexico : State)HistorySources.

7. Sonora (Mexico : State)Social conditions. I. Title.

F1219.1.S65Y47 2012

972.17dc23

2012017367

Introduction

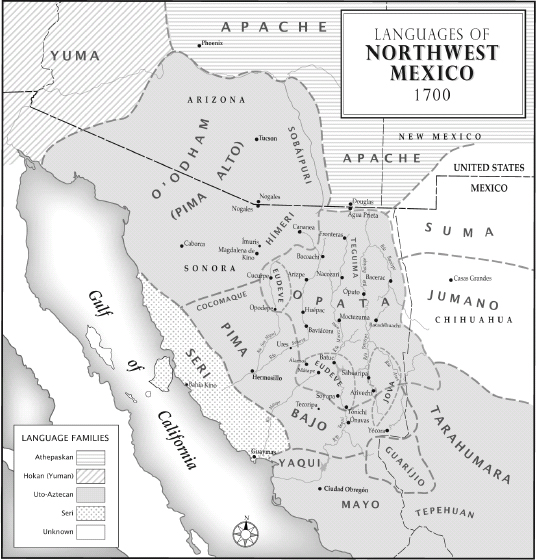

In this book I describe conflicts among three distinct social groupsIndians, religious orders of priests (primarily Jesuits), and settlers (including military personnel)in the Northwest of Mexico over a period of about one hundred thirty years, beginning in the 1640s. Each side had its own interests and frequently struggled to defend them. Indians were usually aligned with Indians, priests with priests, and settlers and soldiers with settlers and soldiers. At times, however, the sides were riven with internal friction and conflict and sought alliances with their purported adversaries. Priests strove to pacify Indians, who in turn resisted the missionary clergys hegemony through a variety of strategies. Sometimes, however, Indians found the missionaries to be their allies. Settlers often encountered opposition from priests to their entradas and operations and found Indians willing to side with them against the clerics. Settlers also sought to dominate Indians, take over their land, and, when convenient, exploit them as servants and laborers. Indians struggled to maintain control of their traditional lands and their cultures and persevere in their ancient enmities with competing indigenous peoples, with whom they often squabbled and fought wars, sometimes allying themselves with priests and settlers against other Indians. The missionaries faced conflicts within their own orders; between orders (Jesuits and Franciscans); and between the orders and secular clergy, and settlers took advantage of this interclerical conflict. Some settlers championed Indian rights against the clergy, while others viewed Indians as ongoing impediments to economic development and viewed the priests as obstructionists.

Settlers, above all, demanded land. In this they had the strong backing

The short- and long-term interests of all three groups resulted in shifting alliances and changing opponents. Still, at the beginning of the 1630s, when the colonial era takes shape in Sonora, the three groups can conveniently be viewed as roughly univocal forces with mostly clear interests. As long as all three laid claim to the same territory, clashes and conflicts were inevitable. Yet without Indians, Jesuits would be without an assignment. And to some extent only the elimination, ejection, or marginalization of the other two groups could fully satisfy the goals and desires of Indians and settlers. In the end, settlers emerged triumphant. Jesuits and their Franciscan successors disappeared from the religious scene and Indians were for the most part pushed into the background.

Each of chapters 1 through 7 is based upon a manuscript, a file of manuscripts, or several folders of manuscripts. I chose these because each permits a distinct glimpse into a conflict pivotal in the social evolution of Mexicos Northwest, especially the state of Sonora. Each conflict underscores a different perspective and reveals the contradictions inherent in the three viewpoints. I came upon some of these manuscripts during research for an earlier book on the patas. Others I discovered while working my way through microfilm copies of files. Still others I found while leafing through documents housed in the Archivo de Indias in Seville, Spain. The documentary foundation for chapter 3, the conspiracies of 1681, came from Luis Navarro Garca, who described them in his important book Sonora y Sinaloa en el siglo XVII. Using his references, I located the original documents in the Archivo de Indias and was able to read them closely. In so doing I arrived at conclusions that differed somewhat from those of Navarro Garca.

Furthermore, scholarly treatment of the archival basis for each of these chapters has been minimal or confined to Spanish language publications, whereas the later conflicts involving Pimans and Seris on one hand and settlers and priests on the other have received wide treatment in English. I have confined my search to Sonora of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries because the archives of that region and that time period have received little attention.

The Missionary Agenda: Jesuits in Mexicos Northwest

The most general description of initial conflicts between Natives of the Americas and Spanish conquerors involves military operations in which the more powerful side defeated the other. The European forces nearly always prevailed. In the case studies in this book (and in most struggles in the Americas between Natives and Europeans), the conflicts were subtler. The most important complicating factor in Mexicos Northwest was the presence of missionaries affiliated with religious orders, primarily Jesuits.

The setting and conditions that gave rise to the conflicts described in this book have been widely elaborated elsewhere but bear repeating.

Initially, at least, clergy and soldiery united as allies in the mission to conquer the pagan Indians, subdue and Christianize them, and open up the Northwest to economic development. The marriage was one of convenience, however, for although the clerics may have viewed the military as allies in their initial entradas, priests and soldier-settlers inevitably clashed. The soldiers represented the authority of ambas majestadesboth majestiesking and God, with special deference to the king, who often granted them titles to land as a reward for service. When they became miners, as they often did, the Crown offered them special incentives and rights, including land grants; hence their first loyalty was to the king. The priests paid homage to the king (usually couching their written references to him with May God protect him) but viewed themselves first as soldiers of God. The different interests of the two groups were bound to collide.

Albuquerque

Albuquerque

In this book I describe conflicts among three distinct social groupsIndians, religious orders of priests (primarily Jesuits), and settlers (including military personnel)in the Northwest of Mexico over a period of about one hundred thirty years, beginning in the 1640s. Each side had its own interests and frequently struggled to defend them. Indians were usually aligned with Indians, priests with priests, and settlers and soldiers with settlers and soldiers. At times, however, the sides were riven with internal friction and conflict and sought alliances with their purported adversaries. Priests strove to pacify Indians, who in turn resisted the missionary clergys hegemony through a variety of strategies. Sometimes, however, Indians found the missionaries to be their allies. Settlers often encountered opposition from priests to their entradas and operations and found Indians willing to side with them against the clerics. Settlers also sought to dominate Indians, take over their land, and, when convenient, exploit them as servants and laborers. Indians struggled to maintain control of their traditional lands and their cultures and persevere in their ancient enmities with competing indigenous peoples, with whom they often squabbled and fought wars, sometimes allying themselves with priests and settlers against other Indians. The missionaries faced conflicts within their own orders; between orders (Jesuits and Franciscans); and between the orders and secular clergy, and settlers took advantage of this interclerical conflict. Some settlers championed Indian rights against the clergy, while others viewed Indians as ongoing impediments to economic development and viewed the priests as obstructionists.

In this book I describe conflicts among three distinct social groupsIndians, religious orders of priests (primarily Jesuits), and settlers (including military personnel)in the Northwest of Mexico over a period of about one hundred thirty years, beginning in the 1640s. Each side had its own interests and frequently struggled to defend them. Indians were usually aligned with Indians, priests with priests, and settlers and soldiers with settlers and soldiers. At times, however, the sides were riven with internal friction and conflict and sought alliances with their purported adversaries. Priests strove to pacify Indians, who in turn resisted the missionary clergys hegemony through a variety of strategies. Sometimes, however, Indians found the missionaries to be their allies. Settlers often encountered opposition from priests to their entradas and operations and found Indians willing to side with them against the clerics. Settlers also sought to dominate Indians, take over their land, and, when convenient, exploit them as servants and laborers. Indians struggled to maintain control of their traditional lands and their cultures and persevere in their ancient enmities with competing indigenous peoples, with whom they often squabbled and fought wars, sometimes allying themselves with priests and settlers against other Indians. The missionaries faced conflicts within their own orders; between orders (Jesuits and Franciscans); and between the orders and secular clergy, and settlers took advantage of this interclerical conflict. Some settlers championed Indian rights against the clergy, while others viewed Indians as ongoing impediments to economic development and viewed the priests as obstructionists.