Praise for David Yetman

Yetmans stories are about colorful characters. Their images will stay with me.

Goodreads

Yetmans enthusiasm is infectious.

Quarterly Review of Biology

Yetman gives especially detailed accounts.

Science

[David Yetman] tickles our brain and gladdens our heart.

Bill Broyles, co-author of Last Water on the Devils Highway

[Yetmans work offers] a key historical reference to fellow scholars as well as the general reader.

Kirstin Erickson, author of Yaqui Homeland and Homeplace: The Everyday Production of Ethnic Identity

Praise for The Saguaro Cactus

This is an excellent primer on a plant that defines our home and demands our respect and protection.

Gregory McNamee, 2021 Southwest Books of the Year

The perfect primer on this distinctive sentinel of the southwestern desert.

Journal of Arizona History

Anyone curious about the saguaros history, ecology, and unparalleled adaptions to the deserts fierce climate will find ample answers to their questions here.

Melissa L. Sevigny, author of Under Desert Skies

The Saguaro Cactus is an extraordinary book written by extraordinary people.

David E. Brown, Natural History Collections, Arizona State University

This contemporary look at one of the icons of the Sonoran Desert is an absolute treat! Any desert dweller or lover of cacti will be delighted to find up-to-date, detailed information on the natural and cultural history of the saguaro, along with an overview of cacti in general.

Craig Ivanyi, Executive Director, ArizonaSonora Desert Museum

Through a series of topical essays, this book is a remarkable examination of the complex world of the saguaro, past and present, including its associated flora and fauna.

Brooke Best, Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas

This compact book is composed of several essays in which the authors apply their respective areas of expertise to comprehensively explore the nature of the giant cacti themselves, their interaction with their natural environment, and their material, cultural, and spiritual impact on human beings.

Christopher M. Bradley, Journal of Arizona History

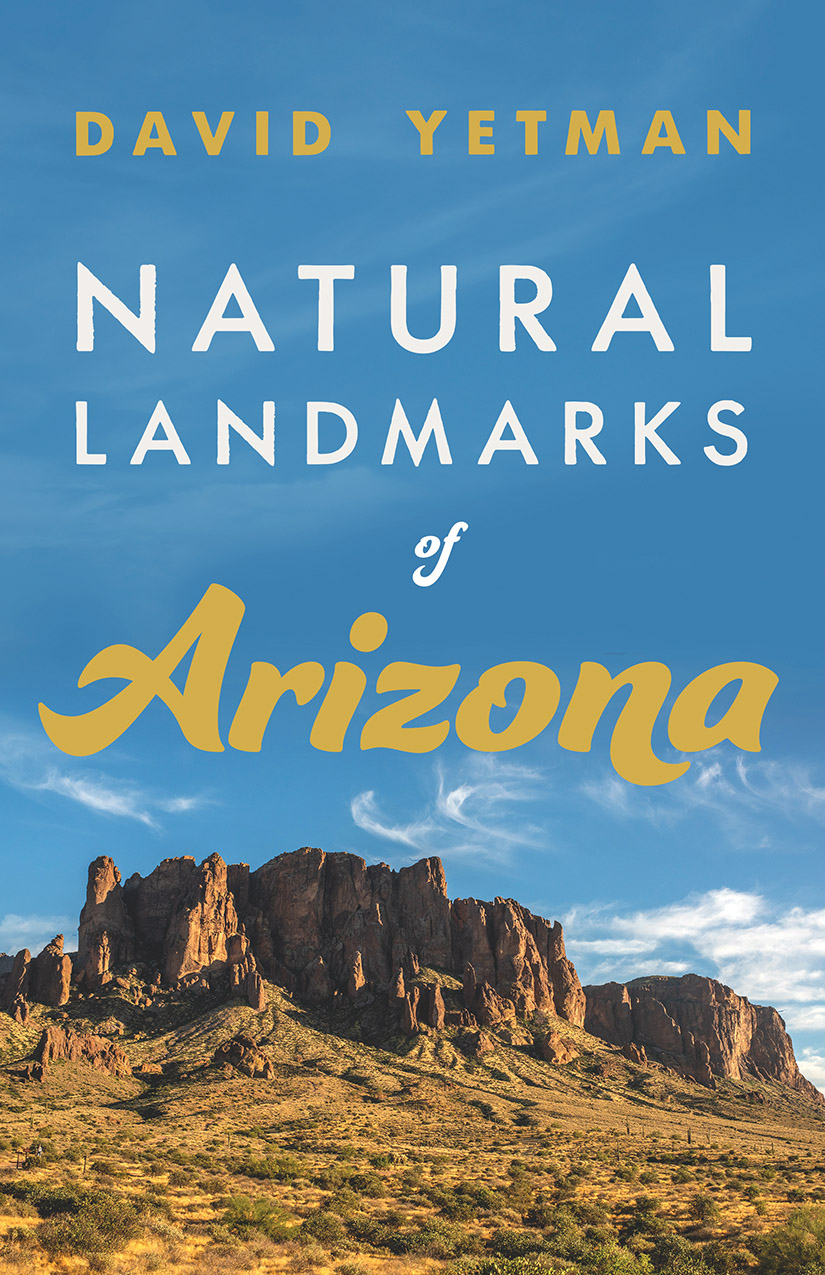

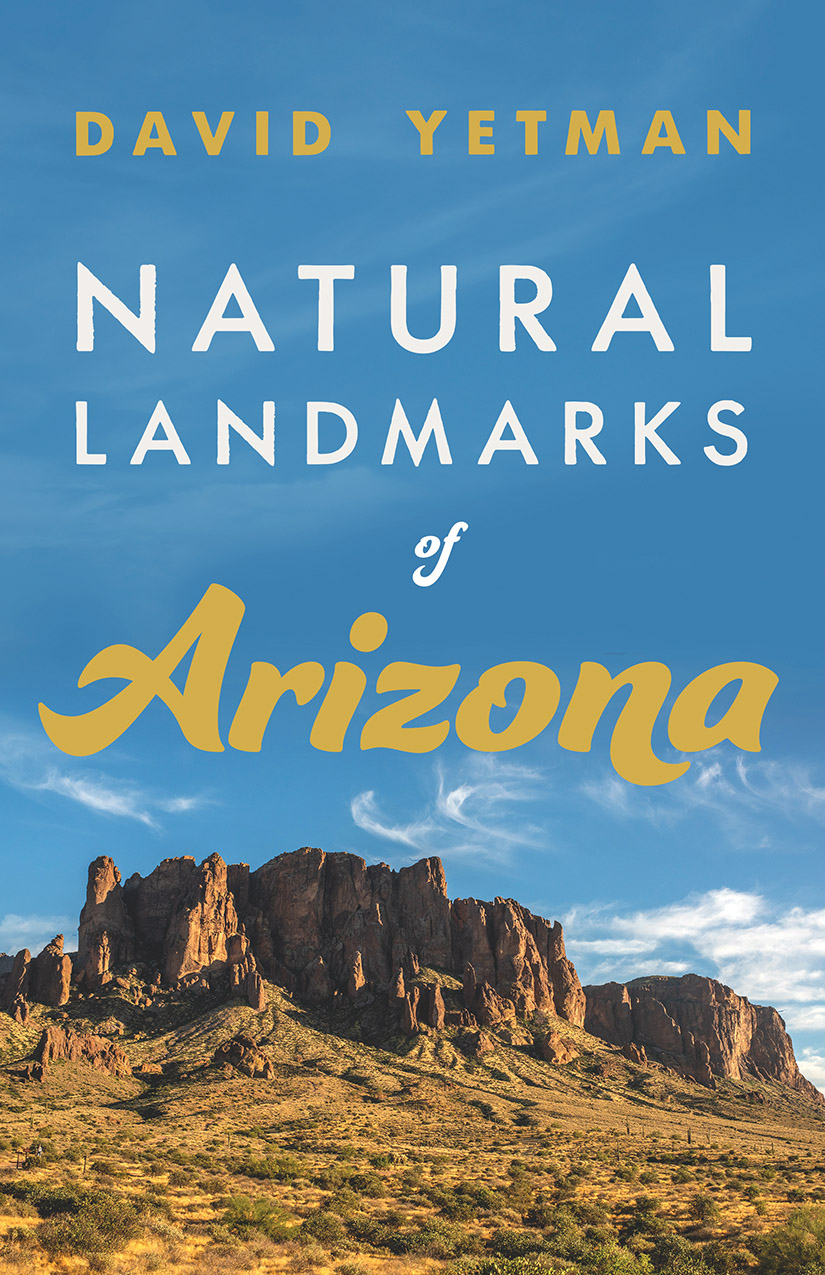

NATURAL LANDMARKS OF ARIZONA

The Southwest Center Series

Jeffrey M. Banister, Editor

Natural Landmarks of Arizona

David Yetman

The University of Arizona Press

www.uapress.arizona.edu

2021 by The Arizona Board of Regents

All rights reserved. Published 2021

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-4245-1 (paperback)

Cover design by Leigh McDonald

Cover photograph of Lost Dutchman State Park by Alex/Unsplash

Designed and typeset by Leigh McDonald in Apollo 10.25/15 and Ganache (display)

The maps on pp. 9 and 13 are by Paul Mirocha.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Yetman, David, 1941 author.

Title: Natural landmarks of Arizona / David Yetman.

Other titles: Southwest Center series.

Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2021. | Series: Southwest Center series | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021004383 | ISBN 9780816542451 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: MountainsArizona. | Geology, StructuralArizona. | ArizonaDescription and travel.

Classification: LCC F817.A16 Y48 2021 | DDC 917.9104dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004383

Printed in the United States of America

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For my brother Richard Yetman, who tugged and guided me into geology

Contents

NATURAL LANDMARKS OF ARIZONA

Why Landmarks?

Landmarks as Locators

This book is about landmarks, parts of the earth that intrude into the Arizona horizon. They are irregularities, reminders that the earth we live on is not flat, a fact so obvious, yet so ignored. Projections of rock rise from the ground into the sky. They orient us. They locate us. They are steadfast through generations. They define where we live and where we are, though we may not reckon as much. They are the monuments that rescue us from geographical monotony. Those who have experienced only flatlands and steppesthe Midwest prairies, Florida, south Texasmay not understand, but one visit to the desert Southwest can rectify that.

My fascination with landmarks began at Duncan, Arizona, a small town that has never received widespread acclaim for the majesty of its landscapes. For me, however, its natural monuments were bewitching and formative. Duncan is an agrarian town of about eight hundred souls, situated on the south bank of the Gila River near the state line with New Mexico. I moved there with my family as a lad from rural New Jersey. For some reason I felt an inordinate need to identify landmarks in this new land and learn their names. From Duncan and its valley rise an array of prominences especially impressive for a young New Jersey transplant. Old-timers in the Duncan Valley taught me the names: Steeple Rock, Mount Royal, Vanderbilt, Apache Box, Ash Peak, Black Hills, Mulligan Peak, and Caneastor, most of them lying in New Mexico north and east of the Gila River. Far in the distance to the west towered Mount Graham, routinely visible from atop the mesa above the town. For me, learning their names was almost as good as climbing them. Almost. I did manage to climb most of them. All of these peaks were grand beyond anything I had experienced in the gentle tree-covered landscape of New Jersey. In that ancient terrain, Cushetunk Mountain was the regional prominence, its unassuming, forested summit 450 feet above its base. In Duncan, it would hardly have merited a name. Duncan has mountains nearby that rise more than 2,500 feet from their bases. Mount Graham, forty-some miles to the west, rises 8,000 feet from bottom to top. These were real mountains. Over time I was inclined to find out about their history and, much later, understand what forces caused them to be there. More than sixty years later, those landmarks and my recollection of them over the years still help define my stay in that small town and that formative part of my life.

This book features natural monuments, those features of Arizonas landscape that stand out as they are and as they were before the arrival of humans. They rise from the earths surface in a manner that we cannot help but notice, though we may pay little attention to them and may even ignore them. We may take them for granted, but they influence who we are and where we are far more than most of us acknowledge.

In the mid-1960s, a decade after I arrived in Duncan, the world of structural geology was transformedshaken, electrifiedby a new theory, now an established fact: plate tectonics. The new scientific paradigm described the earths crust as a composite of massive, floating plates that move independently of each other and from time to time collide, while at other times rifting apart and breaking off. The discovery arose from multiple sources and is credited to multiple discoverers, but almost instantly the revolution drew a phalanx of researchers energized by the new model (and a stern group of resolute and stubborn opponents). When I was young, geologists had detailed maps of terrain, rocks, peneplains, thrust belts, and erosion surfaces. Field geologists were a hardy breed, weathered by constant exposure to the elements, intimately familiar with rocks and their place in geological history. They assembled sophisticated descriptions and cross sections of the landscapes and the rocks that formed them, and many were brilliant analysts. They determined the age of rocks based on their relationship to fossil-bearing strata. They composed geologic maps of astonishing detail, with accuracy unsurpassed even now. One such geologist, David Love, single-handedly created the geologic map of Wyoming. Thirty years later, he equally single-handedly revised it. It remains the authoritative document for the state.

Next page