Minorities and Law in Czechoslovakia, 19181992

Jan Kuklk and Ren Petr

Reviewed by Harald Christian Scheu (Prague) and Luk Novotn (st nad Labem)

Published by Charles University

Karolinum Press

www.karolinum.cz

Cover by Jan erch

First edition

Karolinum Press, 2017

Jan Kuklk and Ren Petr, 2017

This book is written under the auspices of institutional support NAKI of the Czech Ministry of Culture DF12P01OOV013, Problems regarding the legal status of minorities in praxis and its development in long term perspective.

ISBN 978-80-246-3583-5(print)

ISBN 978-80-246-3584-2 (pdf)

ISBN 978-80-246-4239-0(epub)

ISBN 978-80-246-4238-3(kindle)

CONTENTS

- 2.6 The Problem of Autonomy

- 2.7 Development in the Second Decade of the Czechoslovak Republic 19291938

FOREWORD

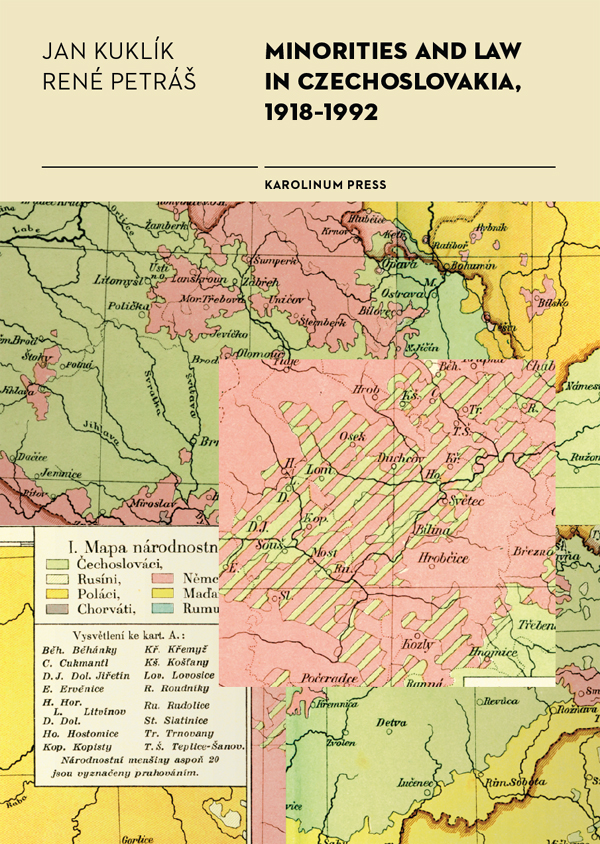

This book provides its readers with an overview of the development of legal status of minorities in Czechoslovakia. Apart from the outline of the law, it is naturally essential to examine basic historical problems in order to make the question understandable for a foreign reader. The greatest interest has been devoted to the interwar period, when the history of Czechoslovakia was distinctly determined by the existence of extraordinarily large minorities, especially German and Hungarian. Large space is also dedicated to the development of World War II and to both historical and legal aspects of the resettlement of the German minority.

Czechoslovakia, which existed between 1918 and 1992, had been through a surprisingly large scope of entirely different historical phases during its development. Czechoslovakia was established after the collapse of the Austria-Hungary. Its foundation was the traditional Czech Kingdom (ergo Bohemia, Moravia and part of Silesia) where aside from Czechs a very numerous German population lived. The second part of Czechoslovakia was Slovakia, which had practically no traditions as a specific entity. Among Slovaks, who are linguistically very close to Czechs, also numerous Hungarians, Germans or Gipsies lived in its territory. During the interwar period Czechoslovakia was the only Central-European state that had a democracy, but numerous minorities, which represented approximately one third of the state population, had often complicated its functioning. Relations with the native states of the Czechoslovak minorities, hence almost all neighbouring countries of the republic, were often tense. The growing tensions between the Czechoslovak state and its national minorities worsened at the beginning of the 1930s due to international crises in Central Europe. As part of its expansive policy, Nazi Germany, headed by Hitler, demanded fundamental changes in the position of the German minority. The need to solve the Czechoslovak minority issues, especially the problem of the Sudeten German minority, served as an excuse for Hitlers threats. The pressure of Nazi Germany enforced secession of areas populated by the minorities, at the Munich Conference in September 1938, which led to rapid disintegration and occupation of the Czech lands by Germany.

During the Nazi occupation the relations between Czechs and Germans worsened and Czechs were regarded second class citizens and persecuted. The Nazi regime especially brought the existence of the Jewish minority in the Czech lands to a tragic end. After freezing and confiscating virtually all Jewish property, Germans started transporting Jews to the Ghetto in Terezn in 1941, and later to extermination camps.

After the war German and Hungarian minorities in Czechoslovakia were accused of collaboration with Nazi Germany and, as enemy citizens, especially in case of German minority expelled from the country. Their property, along with the property of the German Reich, Nazi organizations and Czech collaborators, was confiscated. However, in 1948 the Communist regime was established and it existed here until 1989 with the exception of temporary liberalization in 1968, suppressed by the soviet invasion. After the displacement of Germans, the minority question did not play such a big role anymore, moreover most of the native states of the Czechoslovak minorities were also incorporated into the Soviet bloc and Moscow was naturally not interested in any interstate minority conflicts. The Communist regime collapsed in November 1989, democracy was quickly re-established in Czechoslovakia, except the relations between Czechs and Slovaks were getting worse. This led to disintegration of Czechoslovakia and creation of the independent Czech and Slovak Republics on 1 January 1993. Unlike in some other East European regions, such as in former Yugoslavia, no striking revival of the minority conflicts took place after the re-establishment of democracy, not even in the case of the most numerous Hungarian minority.

The development of legal regulation of national minorities status in Czechoslovakia is exceptionally complicated. Major differences in Austrian and Hungarian legal regulation of relations between nations had existed prior to 1918. The new Czechoslovak state set up quite complicated legislation on minority status within several years after its establishment, where the arrangement of the use of languages in contact with the authorities was especially intricate. An important part in the Czechoslovak legislation was played by the international protection of minorities under the supervision of the League of Nations. The legal regulation of relations between nations had gone through substantial changes during Nazi occupation and in the years immediately after the war and the questions of presidential (pejoratively Benes) decrees and displacement of Germans provoke discussions up to the present time. Even though quite numerous minorities lived in post-war Czechoslovakia as well (especially about half a million of Hungarians), almost no legal status of minorities existed. Although larger groups had, for instance, schools with education in their mother tongue, bilingual signs or opportunity to use their language with authorities. However these authorizations were not derived from legal regulation but only from secret inner instructions or even documents of the Communist Party. Only during the time of temporary liberalization in 1968, the Constitutional Act on the status of national minorities was enacted, along with the Constitutional Act on the federalization of the state. Overall, the minority question was usually on the edge of interest of both the state bodies and the society. This state indeed remained preserved in the Czech Republic, even after the restoration of democracy in November 1989. The minority rights were newly incorporated into the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms from 1991, while the implementing law was enacted only in the independent Czech Republic in 2001. The long and short of it is that the development of the legal status of national minorities in Czechoslovakia has been through series of major changes.

The development of the minority question in Czechoslovakia and its legal regulation is remarkable also from the wider European point of view. During the interwar period, Czechoslovakia belonged among the states which had dealt with the status of minorities the most actively and it also had influence on the creation, operation and termination of international protection of minorities. Complicated legal discussions on the topic of German displacement are still in motion. Czechoslovakia was geographically situated right in the centre of the most dangerous minority conflicts after 1918. It collided not only with the demands of the German minority like many other countries in the region but it also posed as the chief enemy to Hungary, which was traditionally the most revisionist state. Legal solution to the minority question in the Czechoslovak territory has aroused interest of foreign researchers.