Monastic experience in twelfth-century Germany

Monastic experience in twelfth-century Germany

The Chronicle of Petershausen in translation

Alison I. Beach, Shannon M. T. Li, and Samuel S. Sutherland

Manchester University Press

Copyright Manchester University Press 2020

While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors, and no chapter may be reproduced wholly or in part without the express permission in writing of both author and publisher.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 2678 8 hardback

First published 2020

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Cover image: Codex Salemitani IXb: f. 40v (Heidelberg University Library)

Typeset by Newgen Publishing UK

Contents

| Abel and Weiland (1868) | Casus monasterii Petrishusensis, ed. Otto Abel and Ludwig Weiland. MGH SS 20:621683 (Hanover, 1868). |

| ALH | The Annals of Lampert of Hersfeld, trans. I. S. Robinson (Manchester, 2015). |

| CBR | Chronicle of Berthold of Reichenau, in I. S. Robinson, Eleventh-Century Germany: The Swabian Chronicles (Manchester, 2008). |

| CBSB | Chronicle of Bernold of St. Blasien, in I. S. Robinson, Eleventh-Century Germany: The Swabian Chronicles (Manchester, 2008). |

| CBZ | Ortliebi Chronicon, in Luitpold Wallach, Erich Knig, and Karl Otto Mller, trans., Die Zwiefalter Chroniken Ortliebs und Bertholds (Sigmaringen, 1978). |

| CC:CM | Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis |

| CCM | Corpus Consuetudinum Monasticarum |

| CFM | The Chronicle of Frutolf of Michelsberg, in T. J. H. McCarthy, trans., Chronicles of the Investiture Contest (Manchester, 2014). |

| COZ | Bertholdi Chronicon, ed. and trans. Luitpold Wallach, Erich Knig, and Karl Otto Mller Die Zwiefalter Chroniken Ortliebs und Bertholds. Schwbische Chroniken der Stauferzeit 2 (Sigmaringen, 1978). |

| CP | Chronicle of Petershausen |

| Feger (1956) | Die Chronik des Klosters Petershausen, ed. and trans. Otto Feger. Schwbische Chroniken der Stauferzeit 3 (Sigmaringen, 1956). |

| JL | Jaff-Lowenfeld, Regesta pontificum Romanorum |

| Life of Gebhard | Vita Gebehardi Episcopi Constantiensis, ed. Wilhelm Wattenbach. MGH SS 10: 582594 (Hanover, 1852). |

| MGH DD | Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Diplomata |

| MGH Nec. Germ. | Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Necrologia Germaniae |

| MGH SS | Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores (in folio) |

| Mone (1848) | Chronik von Petershausen, ed. Franz Josef Mone. Quellensamlung der badischen Landesgeschichte 1 (Karlsruhe, 1848). |

| PL | Patrologia cursus completus, series Latina |

| REC | Regesta episcoporum Constantiensium 1 (Innsbruck, 1895). |

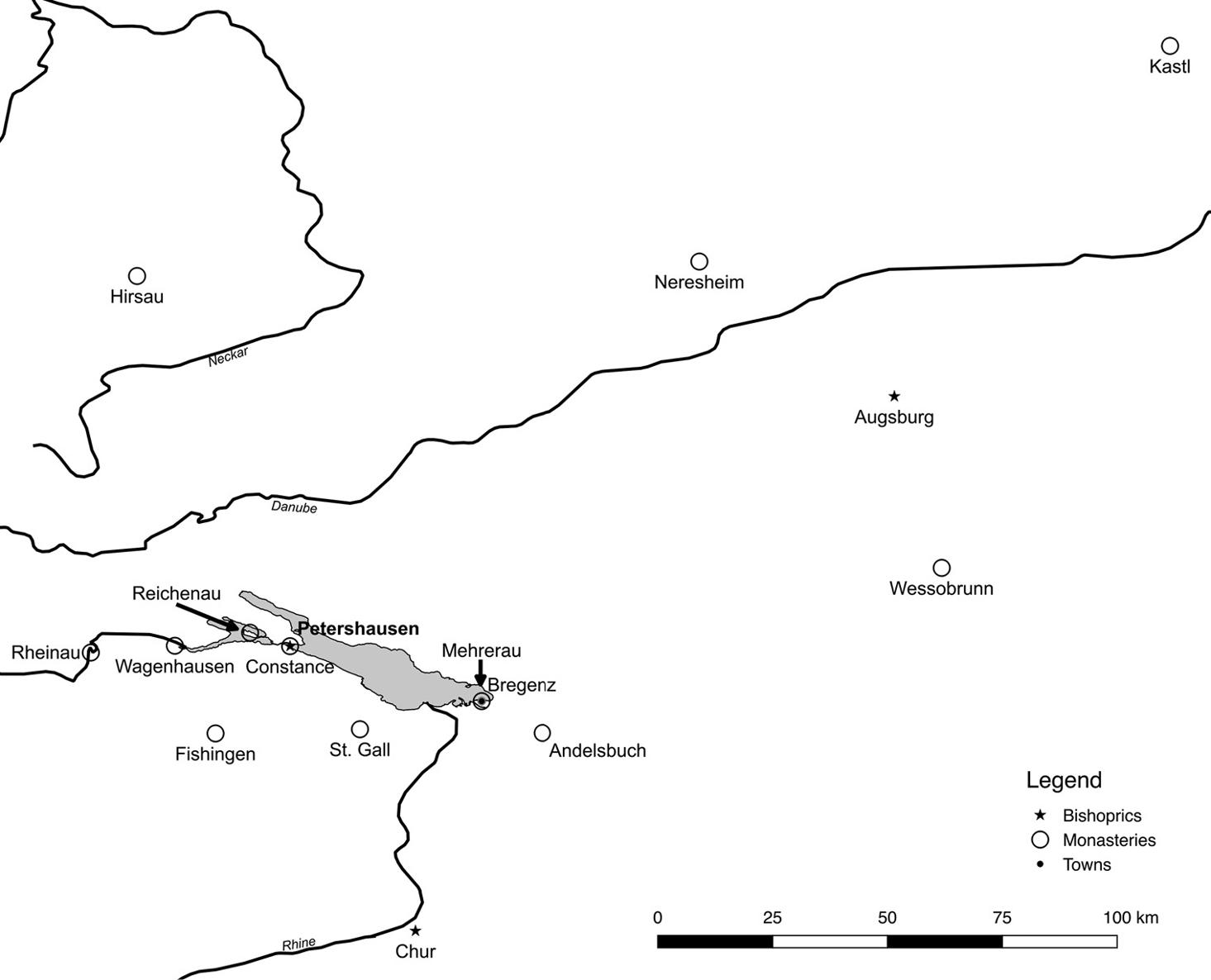

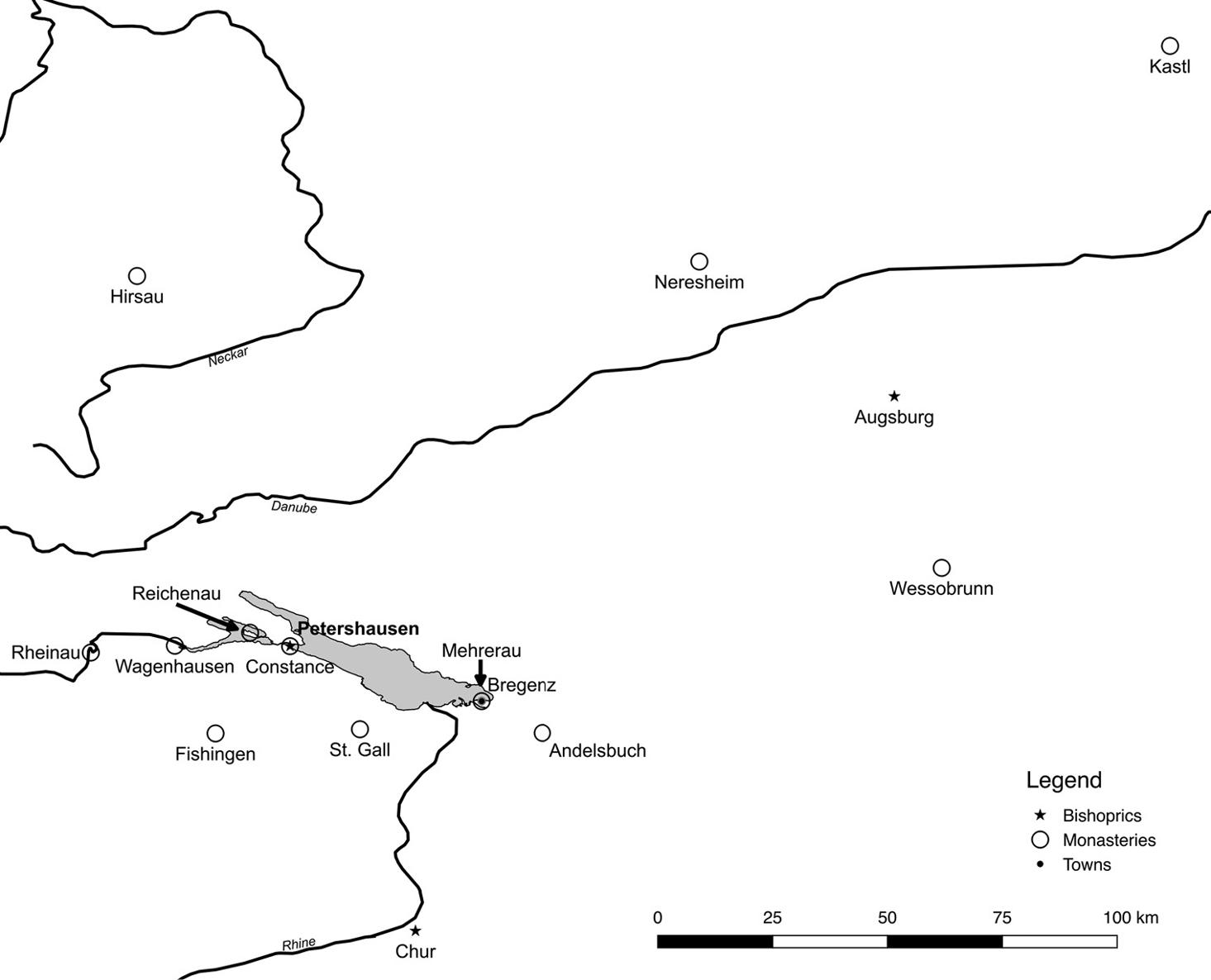

In 983, Bishop Gebhard II of Constance (r. 979995) set out to establish a proprietary monastery not far from his episcopal precinct on the shore of Lake Constance. All of this is the predictable stuff of medieval monastic chronicles.

Historical annals and chronicles abound from German-speaking lands in this period, surely at least partly in response to the ecclesio-political disruptions that devastated the region. Some of the most notable examples come from the pen of Herman of Reichenau (c. 10131054), his continuator Berthold (c. 10301088), and Bernold of St. Blasien, who together documented events from 1000 to 1100. These Swabian chroniclers offer vital accounts of the shifting and violent landscape of eleventh-century Germany. Beyond Swabia, the eleventh-century Annals of Lambert of Hersfeld (in the medieval Duchy of Franconia) constitute the most important narrative account of political events in the kingdom of Germany in the central Middle Ages. A so-called universal history, Lamberts Annals begin with the creation of the world and move into his own time. This is a particularly important source for the turbulent period between 1056 and 1077 a source that the Petershausen chronicler himself seems to have had to hand when he compiled his own account of these events in Book Two. Still other chroniclers narrate the story of the conflict between popes and kings and emperors from the papal perspective. The contemporary chronicler Frutolf of Michelsberg provides the most important, sometimes eyewitness, account of many of the same events from the royal perspective, and his work was extended and adapted (including by Ekkehard of Aura) in the twelfth century.

Reaching for continuity amid the rapid religious and social change of the period a period that for many monastic communities included profound internal change initiated in the name of correction or reform the Swabian monk-chroniclers of the eleventh and twelfth

Like Ortlieb and Berthold, or the author of the Chronicle of Ottobeuren (c. 1210), Petershausens chronicler also sought to bolster the legal and economic welfare of his community by interweaving various charters and privileges some interpolated or even forged to suit present and anticipated needs.

What truly sets the author of the CP apart from the rest, however, is that he continued the work sporadically for some thirty years, from c. 1136 to c. 1164, shifting from retrospective historian to contemporary witness and critic. He speaks with a clear and often feisty voice, revealing a perspective that shifts over time in response to conditions and events both within the monastery and in the broader religious, social, and political landscapes in which it was embedded. The CP begins as a narrative of the triumph of reform; men from Hirsau arrive and take charge, and a wonderful new abbot, Theodoric (r. 10861116), deftly implements the mandated changes. But this narrative of triumph gradually morphs into a narrative of cultural trauma. Subsequent abbots and monks fail to live up to the promises of the reform and the violence of the surrounding landscape finds its way into the community. The chronicler speaks with unexpected candor, often in the first person, as bishop-proprietors clash with the monks, advocates attack with their men, the cellarer pawns precious liturgical vestments, and a monk steals and hides the silver. The interpretation of frightening dream-visions divides the community. Two of the lay brothers beat the cellarer with clubs when he refuses to provide them with needed supplies. And after God permits the total destruction of the community in a massive fire a horrifying inversion of the holy flames of Pentecost the chronicler lays the blame right at the feet of the monks themselves.