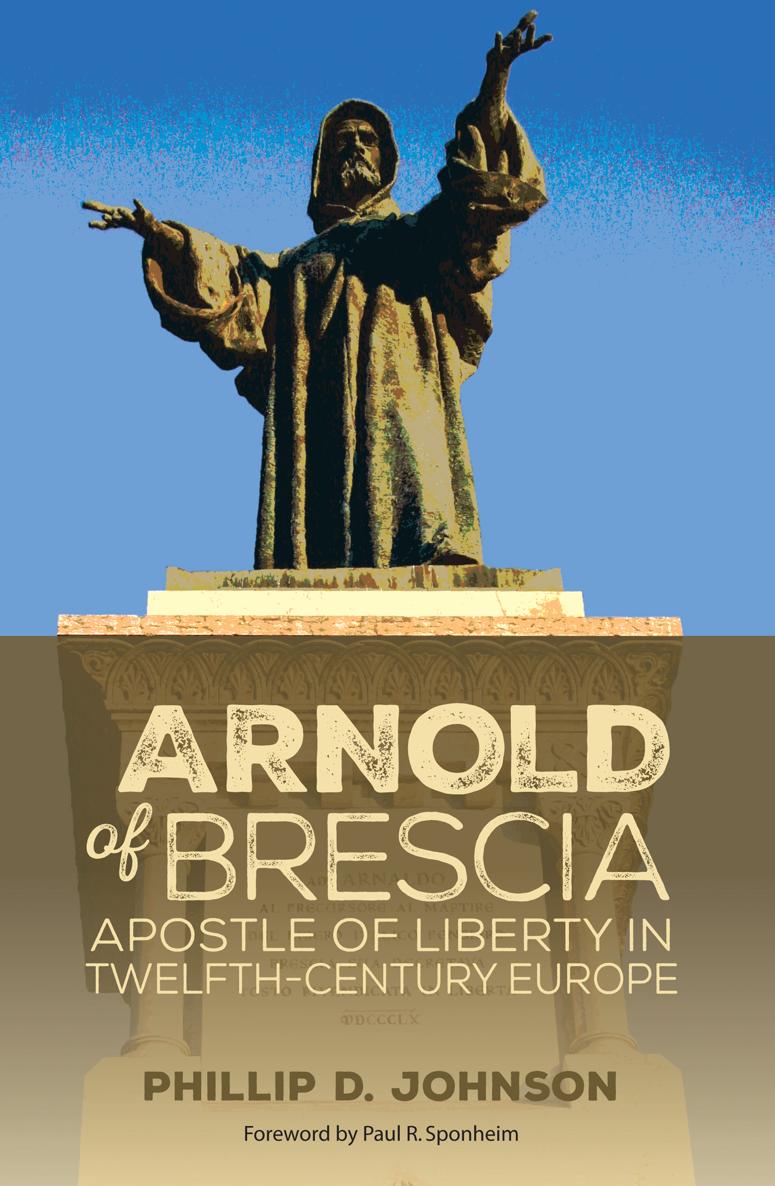

Arnold of Brescia

Apostle of Liberty in Twelfth-Century Europe

Phillip D. Johnson

Foreword by Paul R. Sponheim

Arnold of Brescia

Apostle of Liberty in Twelfth-Century Europe

Copyright 2016 Phillip D. Johnson. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical publications or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write: Permissions, Wipf and Stock Publishers, 199 W. 8th Ave., Suite 3, Eugene, OR 97401.

Wipf & Stock

An Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers

W. th Ave., Suite

Eugene, OR 97401

www.wipfandstock.com

paperback isbn: 978-1-62564-924-9

hardcover isbn: 978-1-4982-8669-5

ebook isbn: 978-1-4982-7579-8

Manufactured in the U.S.A. December 13, 2016

New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989 , Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved

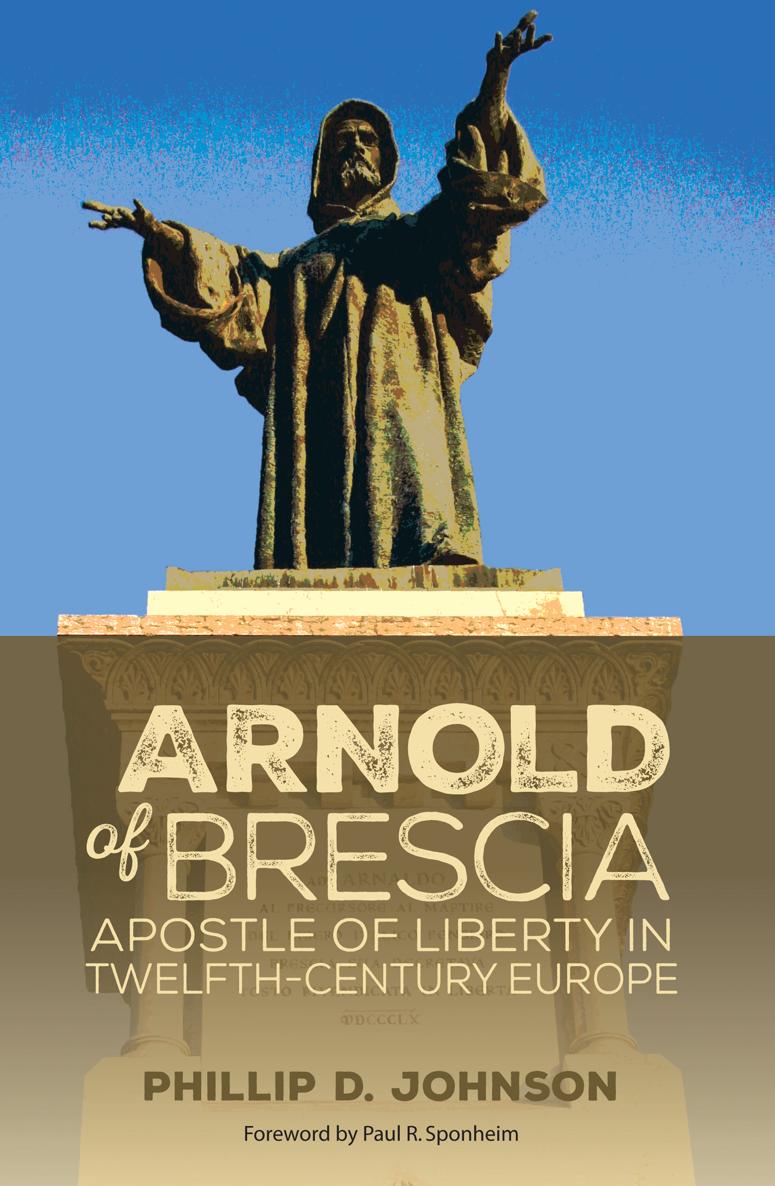

Cover image of Arnold courtesy Alchetron.com

Cover design by Sandy Nelson, www.SandyNelsonDesign.com

Map: Paris in 1180 printed courtesy The University of Wisconsin Press

Map of Rome in the Middle Ages Credit: Historical Atlas by William Shepherd (1923-26). University of Texas at Austin.

Photo of Piazzalle Arnaldo in Brescia, Italy by Scatti & Bagagli

Photo of bust of Arnold in Gianacola Rome by Jessica Spengler

Table of Contents

Dedication

To Eric, Jennifer, Violet, Hazel, and Sandy

But when [Arnold] saw that his punishment was prepared, and that his neck was to be bound in the halter by hurrying fate, and when he was asked if he would renounce his false doctrine, and confess his sins after the manner of the wise, fearless and self-confident, wonderful to relate, he replied that his own doctrine seemed to him sound, nor would he hesitate to undergo death for his teachings, in which there was nothing absurd or dangerous.

And he requested a short delay for time to pray, for he said that he wished to confess his sins to Christ. Then on bended knees, with eyes and hands raised up to heaven, he groaned, sighing from the depths of his breast, and silently communed in spirit with God, commending to Him his soul. And after a short time, prepared to suffer with constancy, he surrendered his body to death.

Those who looked on at his punishment shed tears; even the executioners were moved by pity for a little time, while he hung from the noose which held him. And it is said that the king, moved too late by compassion, mourned over this.

The Bergamese Poet Gesta di federico primi in Italia

Foreword

A t this time, when the church seems urgently called to the discipline of self-examination, it is propitious to receive the resources of this courageous twelfth-century reformer.

The research supporting the thesis of this book is thorough and careful. The primary texts and crucial maps are available in appendices and are copiously referenced in the body of the dissertation. A very useful bibliography is in place. Johnson interacts with conflicting secondary sources, sifting through the evidence, and makes discerning use of his historical imagination. A guiding principle at work for him is to not go beyond what the evidence supports. He lets stand the questions that emerge from the study of this fascinating figure from the twelfth century.

Publication of this dissertation will be valuable for other students of this period. The resources gathered here will be usefully at hand for other scholars studying the medieval church. Persons specifically interested in the influential writings of Peter Abelard will be particularly grateful for the access granted through Arnolds study with this major figure.

More broadly, this window on the twelfth century will make clear that the reforming impulse was present well before Martin Luther and other later reformers who appeared on the scene of history. Johnson drives home strongly the point that Arnold of Brescias teaching and preaching were drawn from and directed to his concern for the ministry of the church.

He tried valiantly to call the church back from the acquisition of secular power. The kind of clarity that one may find in Luthers two-kingdoms teaching is anticipated here. In the study of this theologian, martyred for his convictions, theological students can gain a sense of the life-and-death significance of the faith. They can also be led to appreciate how fully Arnolds teaching and preaching cannot be divorced from his life in community as an Augustinian canon regular.

Johnsons writing has an enviable clarity and will be readable by non-specialists in this period. There is a liveliness to his account of Arnolds life that draws the reader into conversation and contemplation of the readers own need to face the contemporary moral and intellectual challenges comparable to Arnolds. Each chapter has a summary that draws matters together with admirable conciseness.

Paul R. Sponheim

Professor Emeritus, Systematic Theology, Luther Seminary

Preface

M y interest in Arnold of Brescia began when Professor Norton Downs of Trinity College stood and, glass in hand, elbow resting on the mantle of his fireplace, talked about the ferment of the twelfth century. It compared, he said, to the dynamism of the twentieth. He introduced Arnold of Brescia as one example of the excitement of a time of openness and exploration, when intellectual life had not, as yet, hardened into dogmas.

Downs told us this man Arnold was the chief ecclesiastical figure in Rome in the mid-twelfth century. During his time, in large part because of him, the pope was without access to the city. Surprised and intrigued, I began to learn more about him. When I enrolled in the master of theology program at Luther Seminary in Saint Paul to study church history, Arnold was an easy choice for my thesis topic.

Now, fifty years after my class with Dr. Downs and more than twenty-five years after completing my thesis, The Ministries of Arnaldo of Brescia , I am exploring his life again. How do I account for this enduring interest? Why might you be interested?

The impact of Arnolds preaching, teaching, and action has had significant influence through the years. He was a powerful voice for democracy, fostered de facto separation of church and state in Rome while he was city pastor, decried the wealth and secular power of the papacy, enhanced the life of the laity, and was a leading participant in the intellectual enthusiasm of the first half of the century.

His reputation as an outstanding scholar and his faithful Christian life were acknowledged by foes and friends alike. Though he had no force of arms, his influence with the people was such a great threat to the medieval structure undergirding the power and privilege of pope and emperor that they joined forces to put him to death. And, as best they could, erase all memory of him.

He studied and taught with Peter Abelard, the brilliant and notorious teacher who drew a flood of students to Paris during the teens, twenties, and thirties of the century. Exploring Arnolds life leads one into the fresh new world of the twelfth-century, where we meet people among whom were Heloise d Argenteuilscholar, prioress, and wife of Peter Abelard, Bernard of Clarivaux, John of Salisbury, Otto of Freising, Frederic Barbarrosa, and a number of popes. We enter a world of burgeoning communes and lively long distance commerce, an era peopled with serfs, nobles, clergy, wandering scholars, studious monks and nuns, and excited cathedral school students in the midst of an intellectual renaissance.