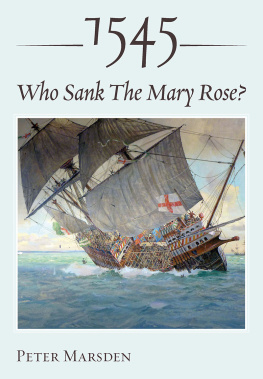

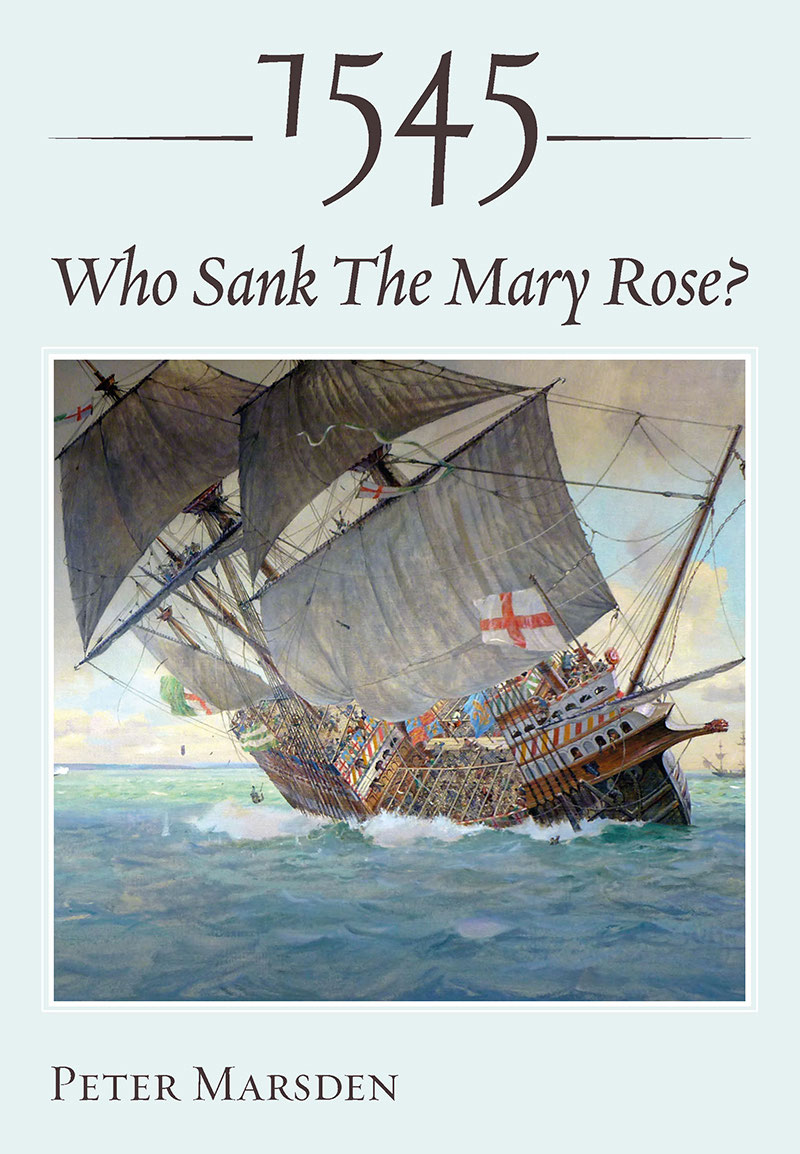

1545

Who Sank The Mary Rose?

1545

Who Sank The Mary Rose?

P

ETER

M

ARSDEN

Copyright Peter Marsden 2019

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

Seaforth Publishing,

A division of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5267 4935 2 (HARDBACK)

ISBN 978 1 5267 4936 9 (EPUB)

ISBN 978 1 5267 4937 6 (KINDLE)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Peter Marsden to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl

All uncredited images from the authors collection. Attempts have been made to find all copyright holders, but the publishers will be pleased to hear of any that may have been omitted.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Why the English warship Mary Rose sank in 1545 with the loss of roughly five hundred lives has been the subject of much debate among historians. We know how it happened, in so far that gunports were left open while she was engaged against the French navy, and that a squall unexpectedly heeled her over and she flooded and sank. But why it occurred has been the problem. At the time the English court blamed the crew; the French believed that gunfire from their galley had caused the disaster; and since the ship was raised other possible reasons, including the pilot possibly being a Frenchman, or that the hired Spanish mercenaries did not understand orders in English, have entered the possibilities. So, the forensic examination of the ship and her contents, when combined with a detailed study of historical records, has complicated the answer. Nevertheless, it has yielded a huge amount of new information and has corrected some long-held but erroneous views as to what actually occurred.

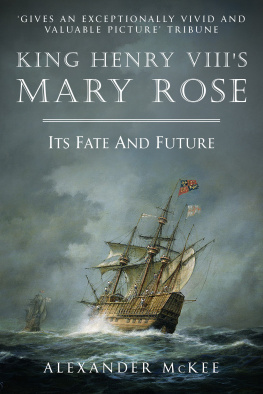

In the year 2000 I was unexpectedly drawn into the matter when Martyn Heighton, Chief Executive of the Mary Rose Trust, invited me to take charge of preparing a book that described the history of the ship. Until then I had observed with awe from afar as Alexander McKee and Margaret Rule, both of whom I knew, had led the discovery, excavation and raising of the ship in 1982, and also the many others who carried out the preservation and exhibition of the ship in a fine new museum at Portsmouth.

I did have some experience relevant to the task as an archaeologist and historian, for in addition to discovering the remains of early London, now at the Guildhall Museum and Museum of London, I had also found Roman, Saxon and medieval ships there, and had obtained a doctorate from Oxford University in maritime archaeology. I had also investigated shipwrecks of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries elsewhere. My only involvement with the Mary Rose up till then had been when my colleagues and I discovered that British law did not recognise the cultural significance of wrecks of historic ships and boats such as the Mary Rose, because they were originally designed to move and therefore were considered to be very large chattels, in the same class as domestic pots. Consequently, I became part of a small band of people, including Alexander McKee and Margaret Rule, who successfully campaigned for the British government to recognise and protect historic shipwrecks. And so the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973 was passed, and subsequently the Ancient Monuments Act 1979 included historic shipwrecks. After years of fighting, we were able to ensure that the Mary Rose was given a protected status.

After the volume on the history of the ship was published in 2003, I was commissioned to prepare a separate book describing the Mary Rose ship herself which was published in 2009. These were part of a series of five volumes, with others on the history of the ship edited by Alexzandra Hildred and Julie Gardiner, that in over two thousand pages described what was then known about the vessel, her history and her contents, and was written by about one hundred specialists in many different fields, from guns to human skeletons.

The books were only ever intended to be interim publications as limited time and funds restricted our research to matters that only related to the ship, with little opportunity to compare her with what was known of other warships in King Henrys navy. Moreover, the ships story in the Battle of the Solent was restricted to her, with little time to study the wider story of the battle. Consequently, some of our conclusions did not address critical issues, such as where most of the men of the ship were accommodated, and how the ship was managed in battle, so the likely reason for the loss of the ship and the death of hundreds of men remained uncertain. Also, a close scrutiny of some English and French records proved that a few were unreliable, particularly the description of the disaster written by John Hooker about 1575 and some aspects of the memoirs of the French nobleman and diplomat, Martin du Bellay, who died in 1559. Hooker, for example, described the sinking as happening in Portsmouth Harbour, and Bellay that the battle started on 18 July 1545. Both are incorrect.

It is over ten years since the Mary Rose Trust published interim details of the story of the ship. Since then there has been time for specialists to reflect on the results of those publications and to carry out further research which has been much more focused. This has resulted in a more developed reconstruction of the ship, and an understanding of the wider history of the events in which she was involved, including the publication of the French records. It also examines what should be in the ship but is absent from the archaeological record, including the absence of the lime pots which are listed as being in the ship when she sank. This period of reflection has also highlighted our need to know when the French fleet actually arrived off the east end of the Isle of Wight, and if the French also attacked the then fishing village of Brighton. Answers are to be found in this book.

In the years that followed the Mary Rose Trust publications, it became clear that the human remains found in the Mary Rose probably did not represent a balanced selection of everyone on board, for the study of the shoes alone show that that they were mostly slip-ons, and so were probably not suitable for wearing by the topmen, sailors, who handled the rigging that was so essential in battle. Also, a programme of DNA studies and a few facial reconstructions was started which opened up new avenues of information.