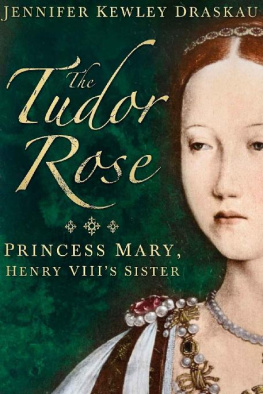

The Tudor Rose

Princess Mary, Henry VIII's Sister

Jennifer Kewley Draskau

STA BOOKS

Revised edition The Tudor Rose

Published by STA BOOKS 2015

www.spencerthomasassociates.com

First published by The History Press 2013

Cover image: Mary Tudor c. 1520,

daughter of Henry VII (1498-1533)

sister of Henry VIII

(Photo by Hulton Archives/Getty Images)

Copyright Jennifer Kewley Draskau 2013

The right of Jennifer Kewley Draskau to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Editor Vicki Villers

For Fiona

CONTENTS

1. The Young Tudors

2. Betrothals

3. Charles Brandon

4. From Esquire to Duke

5. That New Duke

6. Queen of France

7. La Rose Vermeille

8. La Reine Blanche

9. Duchess of Suffolk

10. Married Bliss

11. Field of the Cloth of Gold

12. Doubts and Divorce

13. The Great Whore

14. The Fatal Inheritance: Lady Jane

15. The Fatal Inheritance: The Stanleys

16. The Fatal Inheritance: Lady Katherine

17. The Least of all the Court: Lady Mary

18. Alas !

Abbreviations

Bibliography

1 THE YOUNG TUDORS

A quiver of excitement ran through the chamber. Silken robes rustled as the courtiers craned for a better view. The musicians struck up a merry tune and out he strode, head high, the personification of Englands hopes and dreams, handsome as a young god, the teenage King of England, leading his beautiful younger sister Princess Mary Rose, by the hand. The young Kings wife, dumpy little Queen Katherine looked on, graciously smiling. After a quick glance to check that the Queen approved, the courtiers broke into spontaneous applause.

Katherine, daughter of the Catholic Kings, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, knew that even her best features, her long auburn hair, her fair, healthy complexion and cool grey eyes, were outshone by her gorgeous sister-in-law. At twenty-four, Katherines face retained a childish roundness, but her expression was serene and demure.

Katherine had long practice of smiling even in adversity. Left an impoverished widow by the death of her first husband, Prince Arthur, when her young brother-in-law and husband-to-be, Prince Henry, succeeded to the throne, nothing had been settled. Her own future was still unsure.

Now she had at last achieved her destiny, cherished from childhood: she was Queen of England, bride of the splendid new eighteen-year-old King. Tall and muscular, young Henry VIII attacked life like a lion. He moved with the easy swagger of the trained athlete. His auburn hair was cut straight in the French fashion. Despite his aquiline nose, Henry favoured the Yorks, his mother and his handsome maternal grandfather, King Edward IV, with his broad face, small, sharp eyes and sensual little mouth. Described in 1516 by a Venetian envoy as the handsomest prince ever seen, at this early stage of his career, Henry was also idealistic, liberal and generous. The arrogance and brutality that would tarnish his later years were not apparent. Even his vanity and susceptibility to flattery were effectively masked by his natural charm and genial manner.

Katherine, by nature more reflective than these flamboyant Tudors, lacked their animation and energy. Indulgently she looked on as Mary Rose stole the show. Katherine and the Tudor Princess would remain lifelong friends.

Radiant Mary Rose revelled in the limelight, conscious of her own grace and skill. She had inherited her mothers delicate features, belying the passion, wilfulness and charisma that were the legacy of her fathers Tudor ancestors. Glowing with health and high spirits, splendidly clad, jewels flashing, dipping and swaying in the rhythm of the dance, the glamorous Tudor siblings epitomised the new tide of optimism sweeping through England after the horrors of a protracted and bloody civil war. If ever, since the mythical days of King Arthur, the English court recaptured the fabled glory of Camelot, it was for those few glorious years in the early 16 th century when Henry VIII came to reign.

Sir Thomas More celebrated Henrys coronation :

Now the nobility long since at the mercy of the dregs of the population, lifts its head and rejoices in such a King, and with good reason. Among a thousand noble companions, the King stands out the tallest and his strength fits his majestic bodyThere is fiery power in his eyes, beauty in his face, and the colour of twin roses in his cheeks

Mores coronation ode contains no portent of his bitter quarrel with the King that would culminate in Mores death on the block.

In April 1509, Henry and Mary Roses father, King Henry VII, worn beyond his fifty-two years by his long struggle to hold the throne, had succumbed to tuberculosis, the curse of his dynasty. Few mourned his passing. That Henry had brought peace to the land after the bitter War of the Roses was long forgotten. With the selective memory of afterword, people chose to remember the first Tudor King as tight-fisted and rapacious.

When his seventeen-year-old son was proclaimed as King Henry VIII on 22 nd April, a spirit of rejoicing, powered by an outpouring of love for the charismatic young prince, swept through England. The handsome teenager appeared to embody all the knightly virtues. Surely his reign would usher in a golden world. The undisputed star of young Henrys glittering court was his sister, the beautiful fourteen-year-old Mary Rose, famed throughout Europe as the Rose of Christendom.

Nobody watching this radiant pair, brimming with joyous life, could have foretold that their Prince Charming would become a diseased tyrannical monster, or that the Princess would die young, and that violence and tragedy would stalk her descendants, because they had been chosen by her adoring brother to inherit the throne of England, should he fail to produce an heir. These dynastic devices would prove a lethal inheritance.

The task of a monarch was to secure the throne, through battle, genocide and fratricide if necessary, to consolidate the seat of power through a politically advantageous marriage, and then to secure the succession though the procreation of a sufficient number of male offspring to counteract the dangers of infant mortality. An heir and spare were not always sufficient. Prince Henry was the last chance the newly fledged Tudor dynasty had of surviving, even though the young Tudors parents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, had embraced the important task of securing the succession and celebrating the reconciliation of their two warring houses by producing several offspring.

Henry VII, as the first Tudor King, was determined to found a dynasty where the throne of England would be passed from father to son, rather than usurped by a series of random claimants. By the time their third daughter, Princess Mary Rose, was born, the royal couple already had two promising sons, Princes Arthur and Henry.

In an age of widespread infant mortality, even the birth of a princess a useful political bargaining chip could invoke celebration. However, this princess was born into a climate of intrigue and suspicion. Establishing the dynasty was a brutal business: visitors gaped at the grisly spectacle of decaying severed heads, lopped off traitors and rebels, and now adorning London Bridge.

Only Mary Roses formidable paternal grandmother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond, recorded the birth of a new Tudor Princess in her exquisite Book of Hours on 18 March: Hodie nata Maria tertia filia Henricis VII, 1495. Not much escaped the extraordinary Lady Margaret. During their formative years, she would be a major influence on her royal grandchildren.

Next page