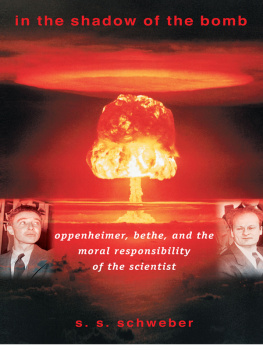

Silvan S. Schweber - In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist

Here you can read online Silvan S. Schweber - In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2000, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2000

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In the Shadow of the Bomb narrates how two charismatic, exceptionally talented physicists--J. Robert Oppenheimer and Hans A. Bethe--came to terms with the nuclear weapons they helped to create. In 1945, the United States dropped the bomb, and physicists were forced to contemplate disquieting questions about their roles and responsibilities. When the Cold War followed, they were confronted with political demands for their loyalty and McCarthyisms threats to academic freedom. By examining how Oppenheimer and Bethe--two men with similar backgrounds but divergent aspirations and characters--struggled with these moral dilemmas, one of our foremost historians of physics tells the story of modern physics, the development of atomic weapons, and the Cold War.

Oppenheimer and Bethe led parallel lives. Both received liberal educations that emphasized moral as well as intellectual growth. Both were outstanding theoreticians who worked on the atom bomb at Los Alamos. Both advised the government on nuclear issues, and both resisted the development of the hydrogen bomb. Both were, in their youth, sympathetic to liberal causes, and both were later called to defend the United States against Soviet communism and colleagues against anti-Communist crusaders. Finally, both prized scientific community as a salve to the apparent failure of Enlightenment values.

Yet, their responses to the use of the atom bomb, the testing of the hydrogen bomb, and the treachery of domestic politics differed markedly. Bethe, who drew confidence from scientific achievement and integration into the physics community, preserved a deep integrity. By accepting a modest role, he continued to influence policy and contributed to the nuclear test ban treaty of 1963. In contrast, Oppenheimer first embodied a new scientific persona--the scientist who creates knowledge and technology affecting all humanity and boldly addresses their impact--and then could not carry its burden. His desire to retain insider status, combined with his isolation from creative work and collegial scientific community, led him to compromise principles and, ironically, to lose prestige and fall victim to other insiders.

Schweber draws on his vast knowledge of science and its history--in addition to his unique access to the personalities involved--to tell a tale of two men that will enthrall readers interested in science, history, and the lives and minds of great thinkers.

Silvan S. Schweber: author's other books

Who wrote In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.