The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Frank

Contents

A Note on the Text

No one has yet found a universally accepted system for rendering Russias Cyrillic into clear Latin script. Academics tend to use precise but rather ugly systems, while everyone else gets by with an easier but more chaotic approach. In my text, I have used the simplest and most familiar-looking version I could find (which is why I have ended up with Trotsky rather than Trotskii or Trockij), but the endnotes follow the precepts of the Library of Congress, which is the best way to track Russian material through online catalogues.

Introduction

The Kremlin is one of the most famous structures in the world. If states have trademarks, Russias could well be this fortress, viewed across Red Square. Everyone who comes to Moscow wants to see it, and everyone who visits seems to take a different view. The only guarantee of a correct response is to choose your position before you come, wrote the German philosopher Walter Benjamin. In Russia, you can only see if you have already decided. In 1927, his decision was to be enthralled.

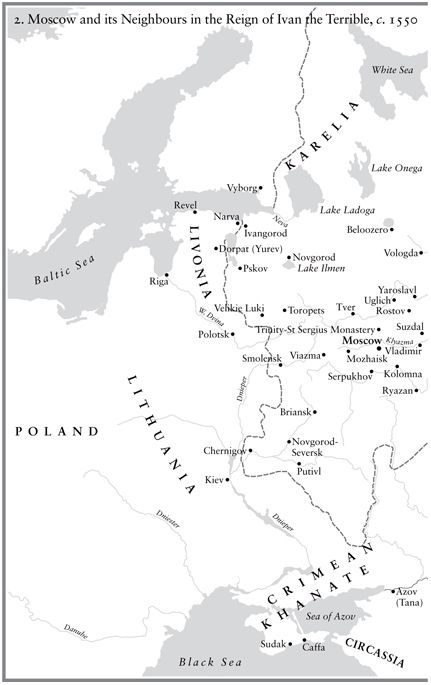

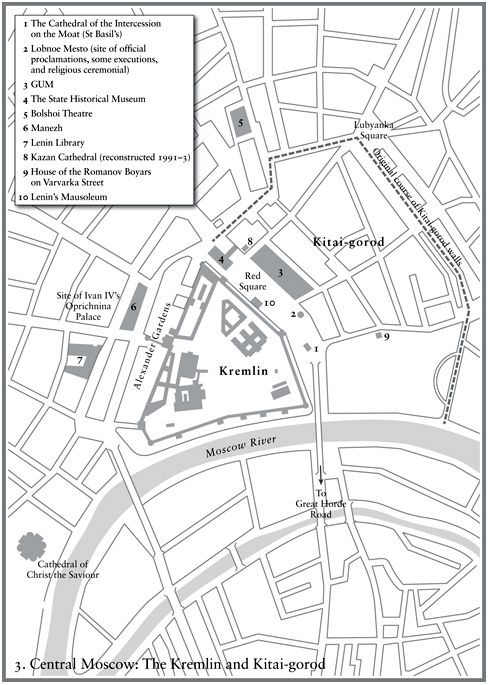

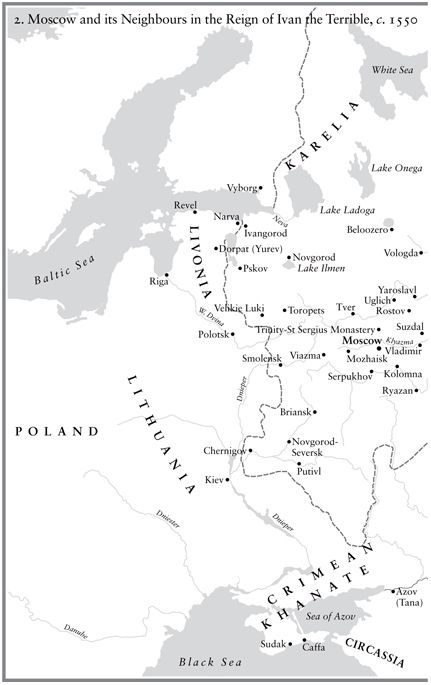

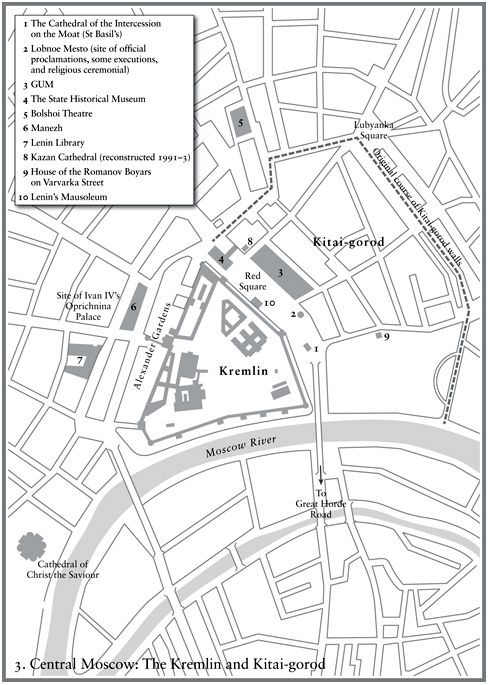

The site still mesmerizes foreign visitors. As the newspaper correspondent Mark Frankland once lamented, there can be few other cities in the world where the feeling is so strong of being carried towards the centre whether one wants it or not. Its walls may not have managed to withstand invading hordes of Mongol horsemen, and they were later breached by Poles and even Frenchmen, but like Russia itself, the citadel endured. Most Russians know that it was here, outside the Kremlin gates, that Stalin reviewed the fresh Red Army troops as they marched off to fight and die in 1941. Less than four years later, in steady early summer rain, the same iconic walls and towers looked down on rank upon rank of marching men. As Marshal Zhukov struggled to control a tetchy thoroughbred horse, the banners of two hundred vanquished Nazi regiments were hurled on to the gleaming stones beside the steps of Lenins mausoleum. The countrys second capital, St Petersburg, may be an architectural miracle, but the Kremlin is Russias wailing wall.

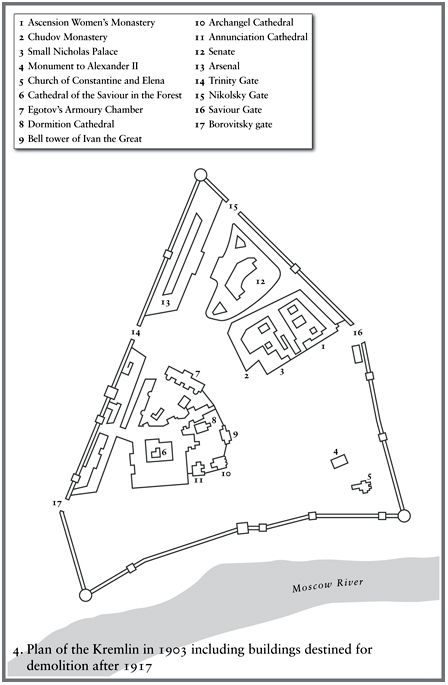

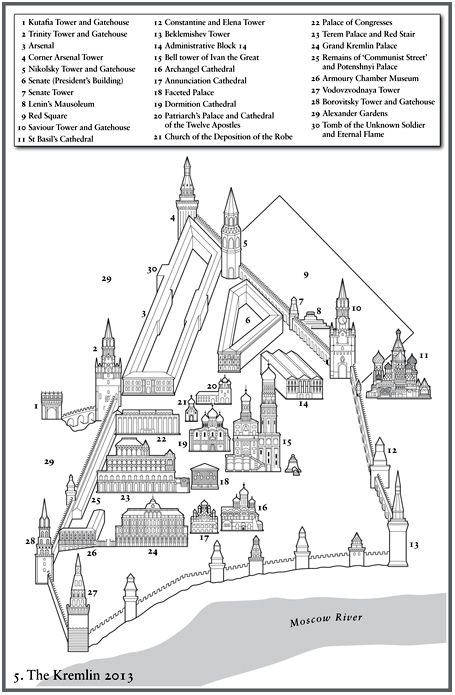

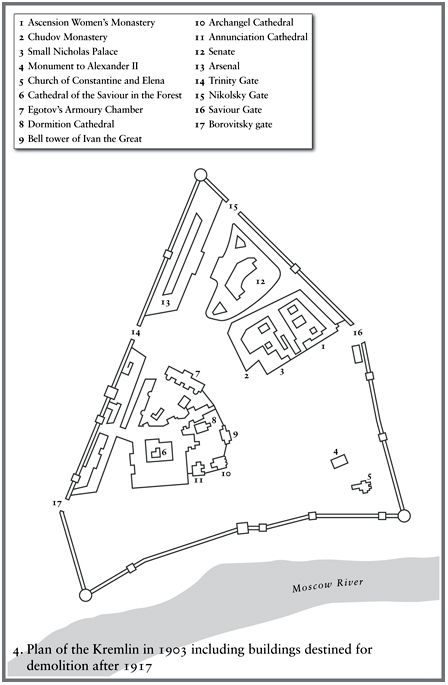

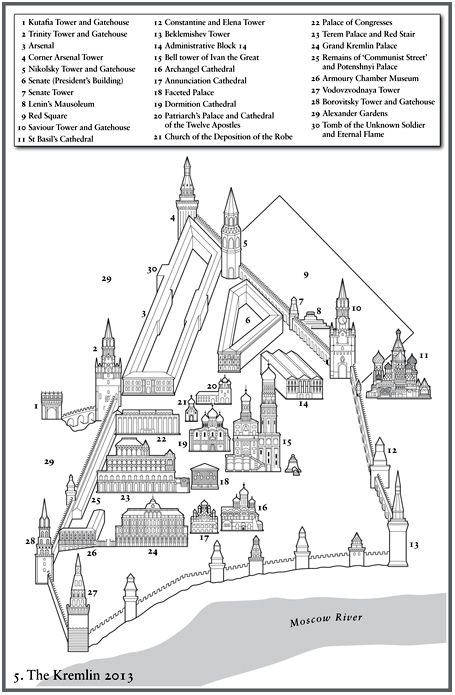

The structure is not democratic. Built from specially hardened bricks, the walls of this red fortress were designed for war. Although they are so elegant that the fact is disguised, they are also exceptionally thick honeycombed by a warren of stairs and corridors that feels like a city in itself and in places they rise more than sixty feet above the surrounding land. The four main gates are made of ancient Russian oak, but their venerable iron locks have long been superseded by the pitiless systems of a digital age. Even now, the Kremlin is a military compound, managed by a person called the commandant, and its subterranean maze of tunnels and control-rooms is designed to survive a nuclear strike. There is no public access to the north-east quarter where the presidents building stands. On Thursdays, in a tradition that dates from the era of the Communist Politburo, the entire site is closed, and it is also sealed, these days, at the first whiff of public disorder. But beauty of the most transcendent kind has flourished in this atmosphere of menace. The Kremlins spired silhouette is crowned by its religious buildings, and the most entrancing of these are clustered like so many jewel-boxes round a single square. From almost any point on this historic ground, the eye will be drawn upwards from the white stones to an effulgence of coloured tile and on to the cascades of gilded domes that lead yet higher, up among the wheeling Moscow crows, to a dazzling procession of three-barred Orthodox crosses. The tallest towers are visible for miles around, standing white and gold above the city. Magnificent and lethal, holy and yet secretive, the fortress is indeed an incarnation of the legendary Russian state.

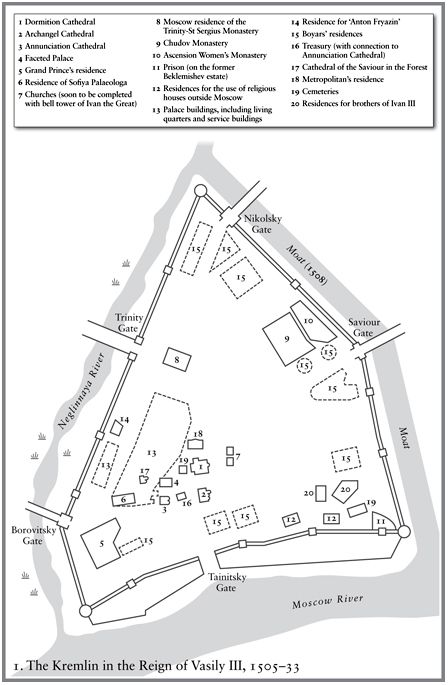

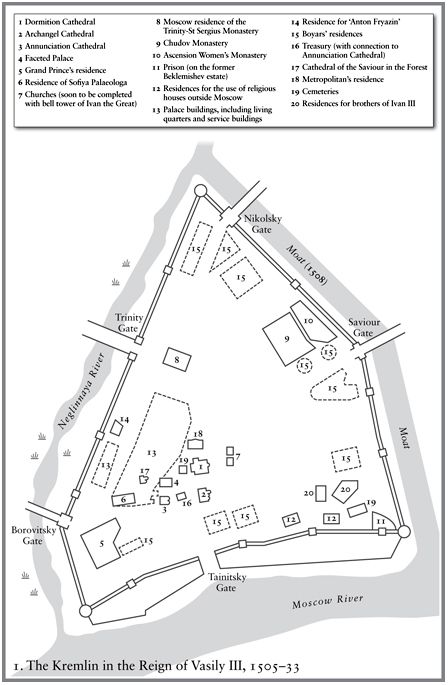

Its spell depends on an apparent timelessness. History is everywhere. The Dormition Cathedral, which is the oldest and most famous sacred building on the site, has witnessed every coronation since the days of Ivan the Terrible. Across the square, in the Cathedral of the Archangel Michael, most visitors can barely squeeze between the waist-high caskets that hold the remains of almost every Moscow prince from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. In the reign of the last tsar, a nationalist court administration had forty-six of the carved stone coffins covered in uniform bronze casings, row upon sombre row, reinforcing the impression of unbroken lineage. By then the shifting of the capital to St Petersburg had long put an end to royal Kremlin burials, but the coronations continued until 1896, and each was followed by a banquet. The fifteenth-century Faceted Palace, where the royal diners gathered in a blaze of diamonds and gold, still graces the western margin of Cathedral Square. Towering behind it, the vast Grand Palace is a nineteenth-century pastiche, but anyone who ventures past the armed police will come upon the curving stair, mutely guarded by stone lions, that leads up to the older royal quarters and the churches that were carefully preserved within. Like Jerusalem, Rome, or Istanbul, the Kremlin is a place where history is concentrated, and every stone seems to embody several pasts. The effect is hypnotic.

It is also deliberately contrived. There is nothing accidental about the Kremlins current appearance, from the chaos of its golden roofline to the overwhelming mass of palaces and ancient walls. Someone designed these shapes to celebrate the special character of Russian culture, and someone else approved the plans to go on building in a style that would suggest historically rooted power. The ubiquitous gold, in Orthodox iconography, may be a reminder of eternity, but for the rest of us it is also an impressive reflection of earthly wealth. From the churches and forbidding gates to the familiar spires that are its emblem, the Kremlin is not merely home to Russias rulers. It is also a theatre and a text, a gallery that displays and embodies the current governing idea. That and the incongruity of its survival in the heart of modern Moscow has long been the secret of its magnetism.

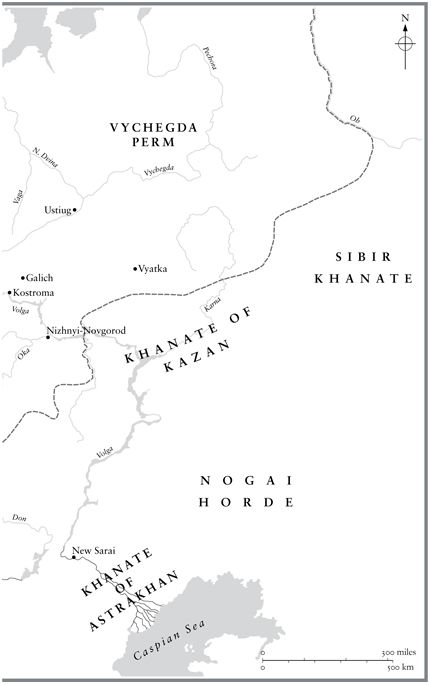

I have been fascinated by the place since I first saw it three decades ago, and its story has seemed to acquire an ever-deeper resonance. A turning point came in 2007, towards the end of Vladimir Putins second four-year term as president, a time when the question of his future was beginning to preoccupy the Russian press. In true arch-nationalist style, his supporters had begun to justify an unconstitutional third term by drawing on the supposed lessons of the past. They argued that the Russian nation had endured because it followed special rules. The people suffered most when there was weakness at the heart of power. The national genius took a unique creative form, they said, and it could flourish only when it was protected by a strong and centralizing state. Obliging textbook-writers duly came up with historical proof. From Peter the Great to Stalin, and from the bigoted Alexander III to Putin himself, the past showed just why Russia still needed a firm governing hand. Even doubters were aware that the alternative was risky. Weak government was something every Russian knew about, for the most recent case had been Boris Yeltsins presidency in the 1990s, a time of national humiliation and desperate human misery. The statist message therefore fell on willing ears. In a poll to find the greatest name in Russian history, organized by the Rossiya television channel in 2008, the implacably reactionary Nicholas I took an early lead, and Stalin followed close behind in second place.

Next page