Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Every effort has been made to contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

Two complications threaten to confound any English-speaker who writes about Russia in 1917. The first is the Russian alphabet, which defies consistent transliteration. In my text, I have opted to use the simplest and most familiar-looking versions of Russian names wherever possible (which is why I have ended up with Trotsky and not Trotskii or even Trockij), but the endnotes follow the precepts of the Library of Congress, which is still the best system for tracking Russian material through online catalogues.

Yet more problems arise with dates. In 1917, Russia still used the Julian calendar, which almost always trailed behind the rest of Europe and the United States (and most of the world) by thirteen days. Since I have had to deal with telegrams (and people) travelling between both worlds, I have often been forced to give both dates at once.

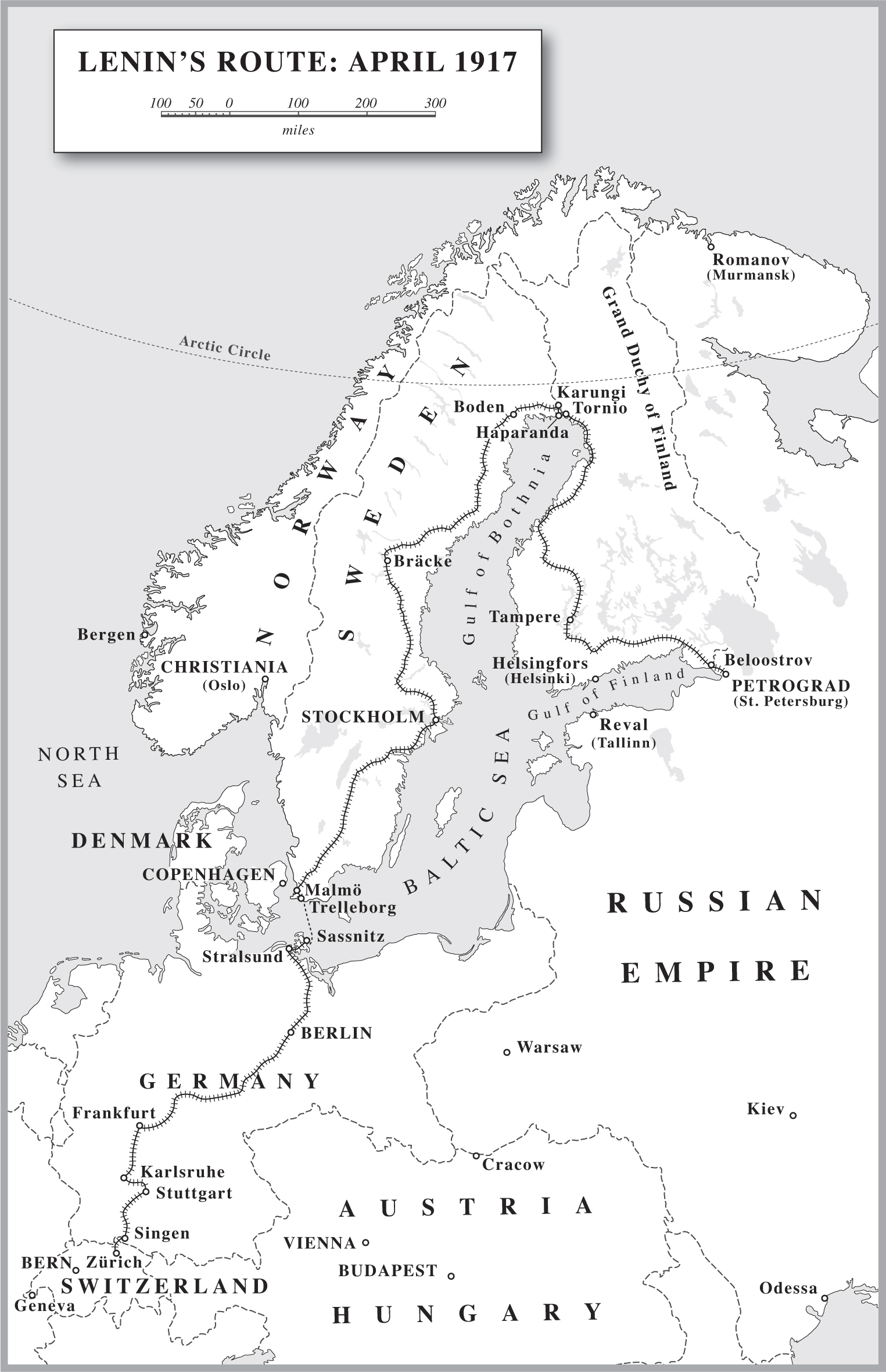

Meanwhile, of course, there are two Easters in this story, for Lenin left Zurich on Catholic Europes Easter Monday afternoon (the date in Zurich was 9 April) and arrived in Petrograd a week later on Orthodox Russias Easter Monday night (which was 3 April to the supporters who were waiting for him).

The masses must always be told the whole truth, the unvarnished truth, without fearing that the truth will frighten them away.

N. K. Krupskaya

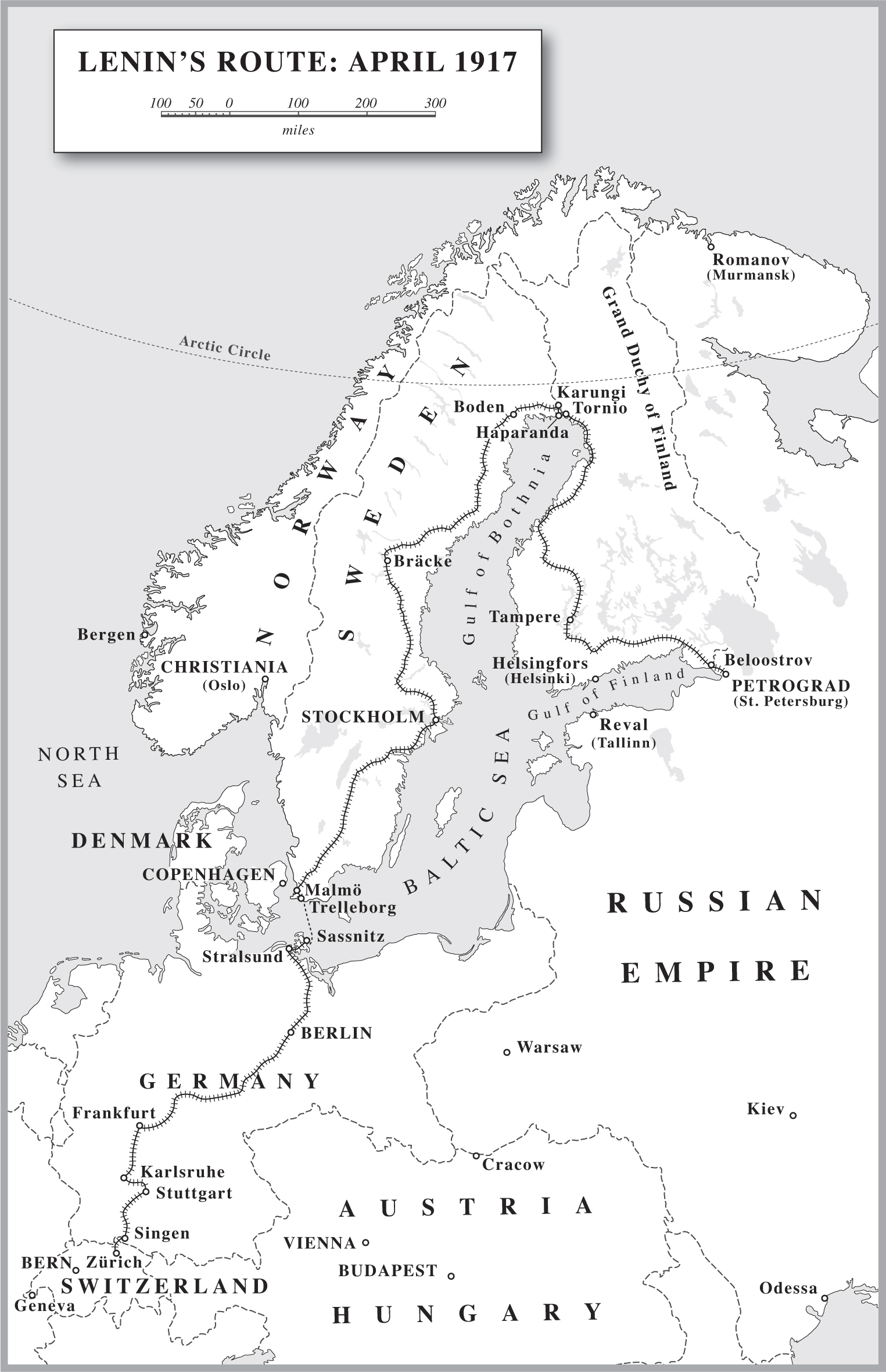

It was Thomas Cook who said it. There are three places in the world that anyone who claims to be a global traveller really must see. The desert citadel of Timbuktu is one of them, another is the old city of Samarkand. The third is a small town in Sweden. A hundred and fifty years ago, it may have been the Northern Lights that drew Cook up to Haparanda. The locals boasted of pirates, too, but every harbour round that coast claimed to have those. Perhaps what really did the trick was the report of a man in a swirling coat, a magic healer, skilled with herbs, who flew above the Arctic night like a great bird.

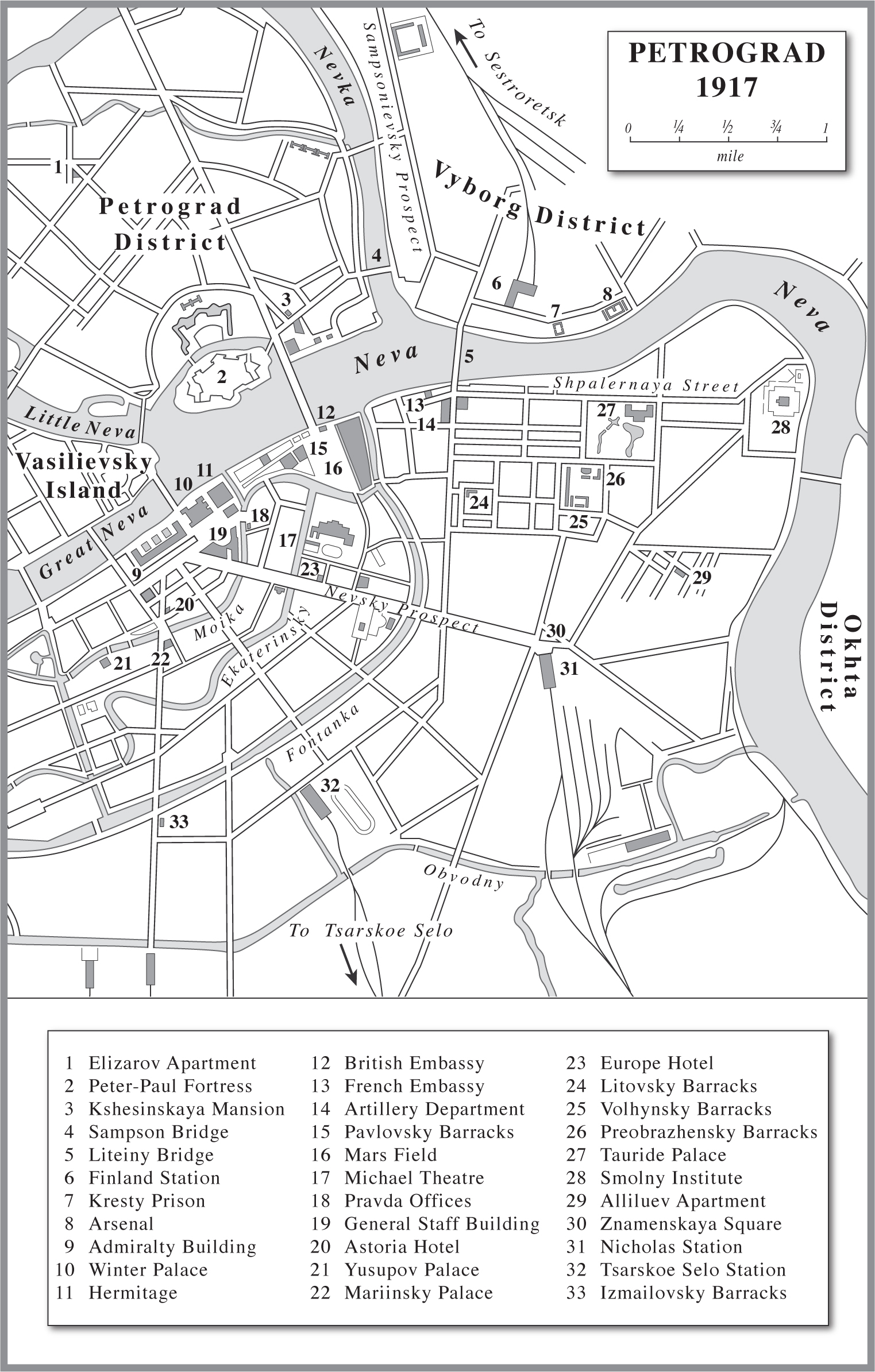

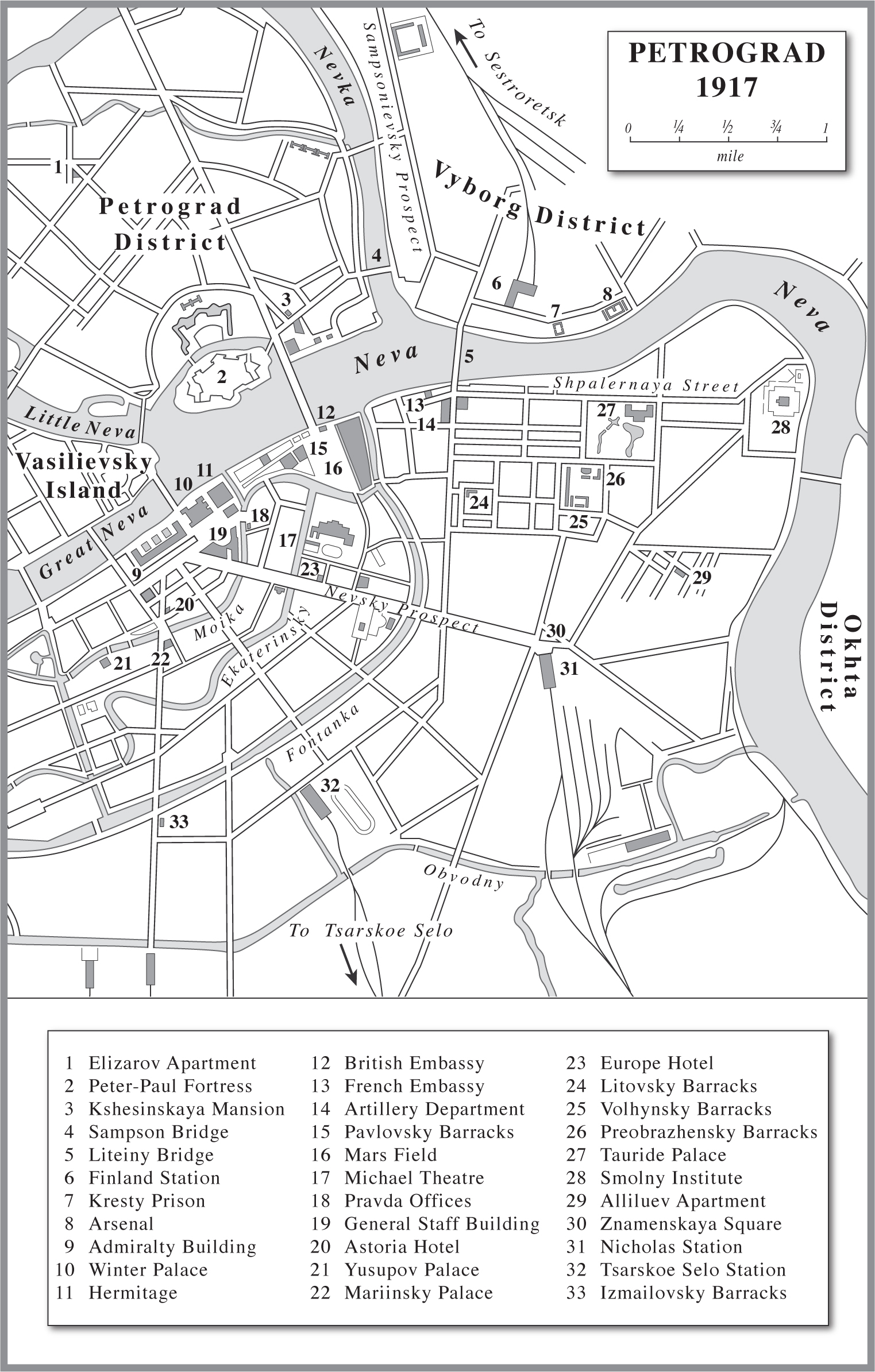

It was not simply that the small town was remote. The place was thrilling, dangerous, right at the end of the known world. Haparanda is situated at the apex of the Gulf of Bothnia, the sea that separates Swedens northern territories from Finland. The area is dominated by a river delta, and at one time the town encompassed a string of low-lying islands as well as some more solid ground towards the west. Other settlements sprang up along the waterside, including a much larger town called Tornio, but life for everyone meant sharing: hunting the regions winter game, taking cattle to pasture on the nearby hills and wading out in the brief thaws to catch the eels that flashed between the floating mats of reed.

The population had nothing much in common with Stockholm (most people spoke a local patois), but the whole zone was part of Sweden until the early nineteenth century. In 1809, however, a treaty concluded at the end of one of Russias many wars with the Swedes decreed that the eastern bank of the river, including the busiest central island, should be transferred to the Grand Duchy of Finland, a territory that the Russians had just snatched for their empire. Marooned on the Swedish bank, Haparanda faced its bigger sister, Tornio, across the river. The two of them were now estranged.

From the moment of its creation, the border never felt entirely safe. The Swedish government could not forget that Russia had ambitions to expand. When vast reserves of iron ore were discovered at Kiruna, less than 300 miles to the north-west, investors in Stockholm were forced to curb their plans for a new railway out of fear that Haparanda might become a gateway for some fresh wave of invading Russian hordes. Swedens age of steam was at its height, but as the lines reached on, like nerve pathways, towards the north, no track was laid to Haparanda. In summer, when the hunters sledges could no longer cross the ice, the only solid link to Finland was a wooden bridge.

What changed things was the First World War. The great powers of Europes Atlantic coast, Britain and France, were allied with the Russian empire now. They needed to send people back and forth, and they had also agreed to provide the Russians with vital war materials, with fuses and precision sights, but direct contact between west and east was blocked. The routes through Germany were shut, of course, and where they were not packed with mines the sea-lanes in the North Sea and the Baltic were patrolled by submarines. Only the land-based route through northern Sweden was viable, albeit gruelling and remote. Thomas Cook died in 1892. If he had thought that Haparanda was exotic once, he should have seen it in 1917.

The rail link was completed in 1915. It was only a branch line, single track, and engines had to steam down from Karungi, some way to the north. Although the route was now an artery for vital wartime trade, the line still stopped short of Finland itself, whose railways (like all those that Russia controlled) used a different gauge in any case. Because the two sides had remained so nervous of each other, everything (including passengers) had to be unloaded at Haparanda station, ferried across the river, hauled up the high bank opposite and reloaded on Russian trains. In winter, sledges dragged by reindeer or stout little horses plied the route; in summer, every boat that could be found was busy on the water.

The bottleneck was clumsy, a time-consuming irritation, but Haparanda was set for a boom. Together with its sister on the Finnish side, it soon became the busiest commercial crossing-point in Europe. Where local herdsmen had once been the only drinkers, the small towns bars now swelled with hustlers, spivs and the secret policemen whose lives slipped by as they observed them. The rooms in the only hotel were booked up for the diplomats and politicians, mainly British, French and Russian, who suddenly began to pass through town. They did not like the climate or the tedious slow trains, but there were no easier options left.

That inconvenient fact also led to the most unlikely of visitations. The Dowager Empress of Russia, Maria Fedorovna, had been in western Europe when the war broke out. She managed to get home herself, but her imperial train was stuck in Denmark and officials in the German government refused to let it steam to Russia along any track of theirs. The situation was awkward, but it was saved by the record freeze of January 1917. When the ice was at its thickest, an army of workmen arrived to lay temporary rails across the Tornionjoki river between Haparanda and the station at Tornio. The imperial train (including boudoir, throne room, kitchens and a mobile electricity generator) was then pulled over, two carriages at a time, and coupled on to a Finnish locomotive on the opposite side. Special castors had been fitted to accommodate the wider gauge. The carriages had barely vanished into Finland when the men were back out on the ice with crowbars to rip up the track.