M iddle Earth and Mordor exist only in the imagination. Thats also where youll find Lilliput, Treasure Island, Oz, Ruritania, Jurassic Park, and Sim City. You cant walk to these places, yet there are detailed maps of all of them.

When I was young, the medieval-looking maps in C.S. Lewiss Narnia books inspired me to draw geographies of my own private worlds, with cities that went to war and great seas crossed by gallant sailing ships. I drew these maps in colored pencil; now I might use a computer.

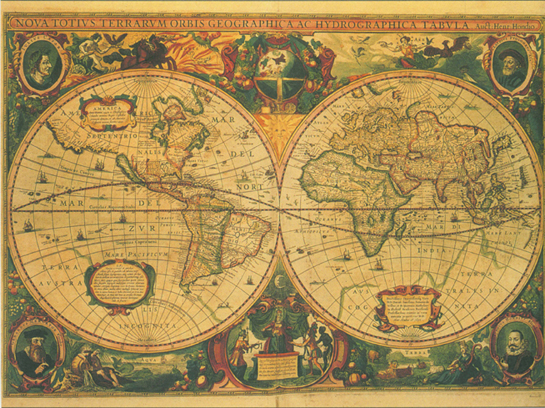

There are many kinds of maps: maps that try to represent land according to mathematical principles; simplified diagrams; and descriptions of the landscape in story and song.

But all mapmaking, even the most scientific, involves some degree of imagination. Mapmakers make one country pink, another yellow. They throw a net over the world and call it lines of latitude and longitude. Now mapmakers are trying to tame and name other planets and solar systems.

So maps are more than a means of showing the lines around your property or your country. They give public names to regions that are mysterious. They create the sense that there are routes from Here to There (even if There is in outer space or our own imaginations). They are another way that we can tell stories.

T HE M APMAKERS S ECRET I DENTITY

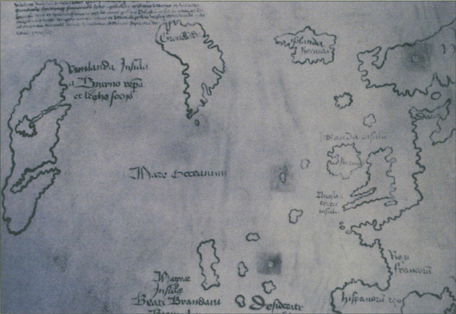

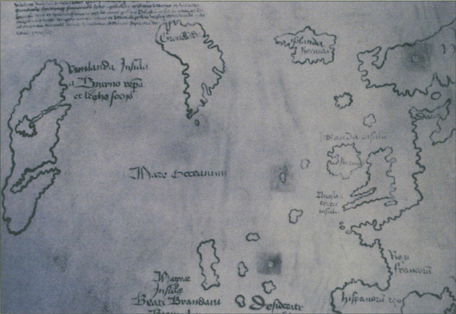

The Vinland Map

SOME TIME IN the first half of the 20th century, someone picks up a pen and begins to fake an antique map. The forgery will prove that the Norsemen, or Vikings, had sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to America long before Christopher Columbuss arrival in 1492.

The forgers pen hovers for a moment above a blank piece of parchment (animal skin prepared as a writing surface). The parchment is no fake. And, although it dates from about 1440 long after the Norse voyages to Wineland or Vinland (the Norse name for North America) around the year 1000 the forger is not worried, since many mapmakers based their maps on earlier maps. What is important is that his map will seem to predate Columbus.

The forger works carefully, writing in Latin and watering his ink so it will appear faded. He knows that medieval mapmakers used inks mixed from iron compounds that erode and leave a rusty stain, and plans to fake such stains with yellowish dye. He might even add holes to the parchment, to make it look like it was eaten by bookworms.

He draws the Mediterranean Sea, Northern Europe, Iceland, and Greenland. Then he dips his pen again, pauses, and commits himself to making the squiggly line that will turn his map into front-page headlines. Beyond Greenland, he draws a line showing the east coast of North America.

He adds notes to his map. One mentions the discovery of a new land, extremely fertile and having vines by the Norseman Leif Eriksson. Another note tells of a journey to Vinland around 11oo by Bishop Eirik Gnupsson of Greenland, who claimed the new land for the Holy Church.

The forger knows a lot about mapmakers of the past. He knows that the first map to use the word America was drawn by a German priest named Martin Waldseemller in 1507. And he knows that any map older than Waldseemllers that shows North America will be a cartographic bombshell.

The Vinland Map is almost certainly a fake. You can see Vinlanda where Baffin Island or Labrador would be, in the upper left. The parchment dates from around 1440, but the ink seems to be from the 20th century.

I n 1957, book dealers tried to sell a Vinland Map to the British Museum in London. The map they offered was bound into an old book about an Italian priests travels to Mongolia. The British Museum experts took a look at the book. They thought the Italian priest part looked genuine. But as for the Vinland Map they smelled a rat and said, No, thank you.

So the book dealers decided to unload their Vinland Map in North America. This time, the map convinced people perhaps because people were ready to be convinced. Scholars had speculated for some time that the Norse had beat Columbus to America because old Icelandic sagas, such as the Greenland Saga and Erik the Reds Saga, described voyages to Vinland around the year 1000. In the late 1950s, archeologists announced that they had found ruins of the Vinland settlement in northern Newfoundland.

North Americans were ready for some hold-in-your-hand proof of the Norse presence in North America. When the book dealers offered the map for sale in North America, a billionaire named Paul Mellon snapped it up for $1 million and donated it to Yale University.

The map was made public in November 1965, just before Columbus Day. This was bad timing for Italian and Spanish Americans who took pride in Columbus, the Italian who had sailed for Spain. They felt it was rude to steal Columbuss thunder, and joined the chorus of English scientists who were already crying Fake!

In 1966 the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC invited experts from all over the world to stop fighting and calmly discuss the maps authenticity. The assembled experts began by questioning the book dealer who sold the map to Paul Mellon. He refused to reveal his sources, but this was not unusual. During World War II, the Nazis had stolen art and book collections from people in countries they conquered. These art objects found their way to dealers after the war. Dealers were reluctant to reveal too much about where their treasures came from, in case the original owners reclaimed them. All the Vinland Map conference could get from the book dealer was that he had acquired the map from a private European collector.

VIKINGS IN VINLAND

Viking poets began to sing the sagas of North American discovery shortly after the year 1000. These heroic poems tell of how warriors led by Bjarni Herjolfsson set off westward from Iceland, checked direction by sighting the stars along their arms, and trusted their single-sail open boats, or knarrs, to get them to Greenland. Instead the winds blew them off course to a new land. From their ships, Bjarni and his men could see tall forests. Fifteen years later, Leif Eriksson followed Bjarnis route and landed with thirty-five colonists. They called the place Vinland because they found fruit probably Newfoundlands sweet berries from which they could make wine.