Using

Non-Textual

Sources

BLOOMSBURY RESEARCH SKILLS FOR HISTORY

A series of detailed research skills guides for advanced undergraduates, postgraduates and researchers in the field of history.

Published:

Using Non-Textual Sources, Catherine Armstrong

Forthcoming:

Elite Oral History, Michael Kandiah

Histories on Screen, Sam Edwards

Using

Non-Textual

Sources

A Historians Guide

CATHERINE ARMSTRONG

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Aim: This book will help the undergraduate history student improve their understanding of non-textual primary sources. It will give them the tools with which to analyse such sources and then hopefully will also give them the confidence to begin selecting such material themselves for use in their arguments.

Let us begin by asking the basic question: what are non-textual sources? I use this term to refer to any source of evidence about the past that is considered primary in nature (i.e. it has something to say directly about the past rather than being mediated through the views of a historian) but that is not primarily textual. Most sources used by historians tend to be either print or manuscript textual or statistical material, such as legal documents, censuses, business archives, letters, diaries or a variety of published works such as books, magazines or newspapers. This book argues that while these items are very important types of evidence, they only partially tell the story of peoples experiences in the past. In order to develop your skills as a historian, it is crucial to expand your repertoire and consider some of the visual, audio, material and environmental evidence that is available to you.

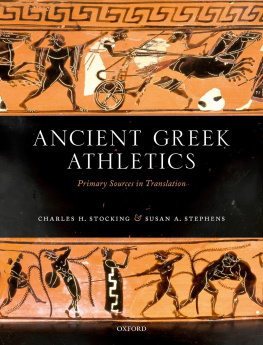

So, having shown what non-textual sources are not, let us consider what they are. Still images, such as paintings, cartoons, photographs or maps play an important role in opening up our understanding about the historical world. We also consider moving images, in the form of feature films, film and television documentaries and news recording. Radio broadcasts, oral interviews and musical recordings are important too. However, two remaining types of source must be considered and these are even less familiar to many history students: the thing and the place. The study of things or material culture has only recently begun to be considered part of a history curriculum. An examination of place in a historical context can also tell us a great deal about the local, and global, significance of that place in times past and can also reveal individual stories of the people that lived there.

Those who have had some training in literary criticism might be surprised by the choice of the term non-textual to describe these sources, and you are partly right; in many ways it is flawed. First, some of the sources we examine in this book that takes written form, whether printed or manuscript. Therefore, non-textual historical sources include everything outside this written form and can be images, still and moving, sound recordings, artefacts and places.

You may have already encountered such sources in your historical study and you may be aware of their significance as source evidence but are still unsure how to make use of them in a critical and analytical way. Then this book is for you. It will help you to learn the language that these sources speak, allowing you to interpret their message and their significance. You can also begin to develop an understanding of how these sources functioned in the past, what they meant to contemporary audiences as well as their significance to historians today. It may sound odd but, in many ways, I hope when considering your own scholarly practice that this book raises more questions than answers, because approaching primary sources as a historian often does leave you with many unanswered questions. A single source reveals many complex and diverse stories about the past, not all of which you may wish to investigate or acknowledge. You may have to be selective. But this book will have done its job if it makes you aware of the fruitful and rewarding possibilities presented to you by these non-textual sources.

The increasing interest among scholars in the last twenty years in visual sources was given an official name: the pictorial turn. The term was invented in 1994 by theorist W. J. T. Mitchell and refers to his belief that pictures reflect our perceptions and identity and that they also increasingly shape the world in which we live. So, as historians we need to engage with this visual world because, even if we are sceptical about Mitchells assumption of the dual influence of the visual, we cannot deny the ubiquity in the last century of the visual in popular culture. For a different reason, the further back in history you probe, the more important the visual becomes this time as a communication medium in semi-literate, illiterate or pre-literate worlds. Therefore, although as historians we might be unsure of the usefulness of engaging with theorists who construct ideas about the visual now, this book shows that such ideas can be applied, with caution, to the past.

However, as Peter Burke has argued, many historians fear that they are concern of the reliability of the source. This book will give you the skills to overcome your concerns or at least to address them so that you feel confident enough to approach non-textual sources and even to locate them for yourself.

In this book, you will find that the majority of the examples and source evidence come from a European or Anglo-American context. This reflects two issues with the study of visual material. First, all scholars work with what is familiar to them and the material that their field produces. I am a historian of the relationship between England and her North American colonies prior to the War of Independence. I teach modules on American history from the first contact period to the late twentieth century. Therefore, my personal expertise and interests have skewed the evidence presented here. Of course, I am not claiming that visual material from other parts of the world, such as that produced by Native American cultures, African, Indian, South East Asian, Australian, the Pacific Islands and many others is not as important. However, this does reveal a more serious theoretical point that much of the scholarly discussion around visual culture is Western, or Eurocentric. For example, trends in the history of art are defined by recourse to a canon of Western artists from the ancient world to the present day. This is not just a problem with visual material; explorations of literature often reveal the same thing, with the pantheon of authors studied in English literature degrees being mostly white, male and from Northern Europe or the United States. It is important for you to understand the perspective from which your primary sources are created but also the perspective of the theorists and scholars from whose work you are borrowing. Do not simply imitate their approaches without being critical of them.

Although I rejected the structuralist definition of a text, as mentioned above, I do not wish to deny the relevance of all postmodern theory to the analysis of visual material. In fact, much of what Im trying to do in this book involves alerting history students to the significance of the ideas of semiotics. This theory states that the visual image is constructed as a system of signs that communicate with us. Why is this useful for historians? When looking at non-textual material we need to understand how present and past audiences derive meaning from that image. Is there something intrinsic in the image itself that creates the message? Or by bringing our own historical context do we create the message ourselves? Does the image mean something different to everyone?

Next page