Jonathan Sumption

EDWARD III

A Heroic Failure

Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

| Edward the Confessor | James Campbell |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [ Cromwell | David Horspool ] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III & Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

1

Edward of Windsor

(13121330)

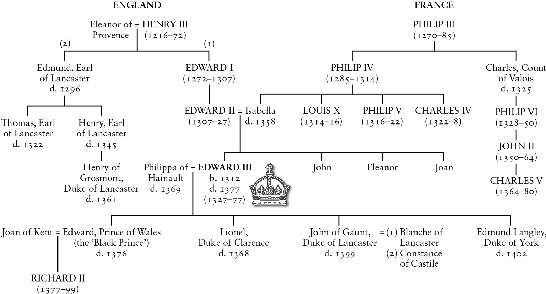

Edward III was King of England for fifty years. He was a paragon of kingship in the eyes of his contemporaries, the perfect king in those of later generations who have romanticized the institution of monarchy. He cut a fine figure. He led his armies in successful wars. He maintained a magnificent court. Venerated as the victor of Sluys and Crcy and the founder of the Order of the Garter, he was regarded with awe even by his enemies. Charles V of France, who was largely responsible for undoing his work, hung his portrait in his study. His great-grandson Henry V studied his campaigns and adopted his war aims. A century and a half after his death, Henry VIII, the last English king to toy with the idea of conquering France, consciously modelled himself on his famous ancestor. In the seventeenth century, the officials of Charles I copied documents from the public records to discover how he had managed his wars, while the parliamentary opposition held up Edward as a model to demonstrate the failures of their own age. King George III commissioned paintings from Benjamin West of the great occasions of Edwards reign. Prince Albert and Queen Victoria dressed up as Edward III and Philippa of Hainault at fancy-dress balls. Yet for all the attention devoted to him in his lifetime and since, Edward IIIs personality is largely hidden behind the mask of kingship and a screen of uncritical adulation. Success is admirable in a king, but failure is compelling and usually better recorded. We know a great deal more about the personality of Edwards neurotic predecessor, Edward II, and of his vulnerable and unstable successor, Richard II, both of whom defied the conventions of their age and were deposed and murdered.

Edward was born at Windsor Castle on 13 November 1312. The country which he was destined to rule was one of the two principal nation-states of Europe, the other being France. But with around five or six million inhabitants, England had only about a third of the population of its neighbour. A large part of its territory was forest and some regions, especially in the west and north, were very thinly settled. London, the only English town to stand comparison with the major cities of continental Europe, probably had fewer than 50,000 inhabitants, as against about 200,000 for Paris, then the largest and richest city in Europe. England, however, was endowed with a precociously advanced system of government which made its kings powerful beyond anything warranted by its comparatively modest resources. Unlike France, which had developed as a nation by the gradual coalescence of ancient autonomous provinces, each with its own distinct political and cultural traditions, England had been conquered in the space of a few years in the eleventh century by the Norman kings, who had created a centralized, unitary state

It is one of the paradoxes of Englands medieval history that in spite of its strong central institutions it was known mainly for its chronic political instability. In fact, the two things were connected. The fortunes of a powerful, centralized monarchy were inevitably dependent on the personality and political skills of the reigning monarch. Lacking the police powers of the modern state, even the most organized of medieval governments depended on the tacit assent of their leading subjects. In England, this meant some sixty baronial families, whose political power was based on their possession of large acreages of rural land and on their influence in the landowning communities of the counties. These men regarded themselves as the kings natural counsellors. Few of them were hungry for political power, and hardly any wanted to engage in the daily grind of government. But they resented exclusion more than they loved power. Their relationship with the crown was important to them. It was a major source of status and patronage. Twice in the previous century the baronage had intervened to take power out of the kings hands when the government had manifestly broken down, or when they conceived that power had already been taken out of his hands by others who were monopolizing his favours in their private interest.