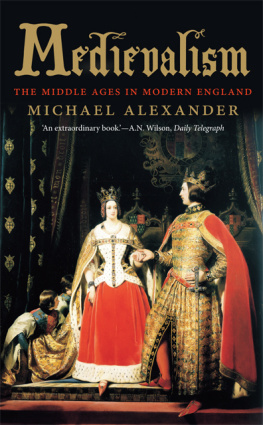

MEDIEVALISM

Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund.

Copyright 2007, 2017 Michael Alexander

Published in paperback in 2017

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Typeset in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Hobbs the Printers Ltd, Totton, Hampshire

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Alexander, Michael, 1941

Medievalism: the Middle Ages in modern England/Michael Alexander.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0300110618 (alk. paper)

1. MedievalismGreat BritainHistory. 2. Great BritainIntellectual life.

3. Gothic revival (Architecture)Great Britain. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in

art. 5. Civilization, Medieval, in literature. I. Title.

DA110.A44 2006

942.01dc22

ISBN 978-0-300-22730-7 (pbk)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Mary

Contents

Illustrations

Thomas Rogers, The 3rd Marquess of Bute (John Patrick Crichton

Stuart), c. 1896.

John Everett Millais, A Dream of the Past: Sir Isumbras at the

Ford, 1857.

Edward Burne-Jones, When Adam Delved and Eve Span, illustration

for Morriss A Dream of John Ball, 18867.

George du Maurier, Ye sthetic Young Geniuses, Punch, 21

September 1878.

Preface

A new interest in medieval things surfaced in England in the 1760s and with it a revival of medieval forms, manifest in literature and in architecture. At first this modern medievalism was experimental and uncertain. A more serious attitude to the medieval past developed during the long war with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. A longer historical perspective altered the ways in which the English and perhaps the British came to think of the evolution of their society and its political arrangements. In the 1830s this Medieval Revival affected religion, and produced major changes in architecture, and then painting and the decorative arts. The countrys idea of its history, and of its identity, changed.

In 1960, the founding editor of Penguin Classics, Dr E.V. Rieu, received a proposal for a book of verse translations, to be called The Earliest English Poems. The proposal consisted of trial versions of two Old English elegies, The Ruin and The Wanderer, with a list of other poems to be translated. Dr Rieu, who had sat Classical Moderations in Oxford in 1908, accepted the proposal, though the translations were in verse, not the readable modern English prose which was his policy for the series. Over lunch at the Athenaeum, he offered his undergraduate guest a piece of traditional advice: You will find it a very good practice always to verify your references.

Completing that book entailed the verification of many references, and the translator, my younger self, eventually took to teaching English literature, modern and medieval, to translating Beowulf and the Exeter Book Riddles, making glossed editions of Beowulf and of Chaucer, and writing about modern poetry.

In the 1980s, British universities were told by British governments to reward research, not teaching. One of the evil consequences of this directive was that the common inheritance of English literature was further enclosed into fields of academic research. As a gesture of resistance, I wrote a history of English literature from The Dream of the Rood to The Remains of the Day. The writing of this history uncovered a story, known to some scholars but not to most educated readers, of the recovery of the past and the re-introduction in the 1760s of new medieval models into modern literature, and gradually into other fields: politics, religion, architecture and art. The following essay in cultural history is an attempt to trace the very far-reaching results of this re-introduction.

Acknowledgements

The Middle Ages, blacklisted at the Reformation and looked down on in the Enlightenment, were long regarded as of little or no interest. Willed amnesia gave way, from about 1760 onwards, to curiosity and to gradual rediscovery, a rediscovery which had a variety of lasting effects.

Medievalism is an awkward term, referring not to the study of the Middle Ages but to the adoption of medieval models. Much of what is written on medievalism is grandly general (Victorian medievalism was a reaction to the Industrial Revolution) or specialised, focusing on one field Gothic Revival architecture, or Pre-Raphaelite painting or one corner of a field, such as (an imaginary example) the use of heraldry in stained glass in Edwardian country houses. A more comprehensive account, longer in time and wider in scope, ought rightly to begin generations before the reign of Victoria and to continue for generations after it; and to look beyond architecture and the arts to the generation of new social and religious ideals. The following attempt, an essay in general cultural history, has its starting points in literature, since that has been my profession. I have made verse translations of Old English poems, and edited medieval texts, but my university teaching has, by choice, chiefly been of classical English literature since Chaucer.

During the writing of A History of English Literature, I became curious about the opening up, in the eighteenth century, of the Middle English literature which lay behind Geoffrey Chaucer. Thomas Percys publication of medieval vernacular verse, in his Reliques of Ancient English Poetry of 1765, proved popular and was imitated. Missing links of medieval literature were imaginatively supplied by Macpherson and Chatterton. This romantic rediscovery of medieval romance was once quite well known, for it was promoted by the most influential writer of the nineteenth century, Walter Scott, whose own medieval verse romances had a wild success. Coleridge had imitated medieval ballads and romances, Keats was to follow, and Tennysons many readers mourned for the death of King Arthur. It was in Queen Victorias palmiest days that medievalism was at its height. Yet medieval examples also acted with revived power upon Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden. These modernist poets were loudly anti-Victorian, and Victorians were often medievalists. But this does not mean that modernist poetry is never medievalist. On the contrary, as is clearly laid out in the final chapters of this book, the leading modernists were very often medievalist. The more original parts of this book are the opening and closing chapters.

I began to explore the literature of the Medieval Revival with undergraduates at St Andrews, a university whose graduates include William Dunbar and Gavin Douglas. I thank the students who took this way through the backwoods of literary history, and my fellow explorer, Dr Chris Jones. He kindly read my drafts, as did Professor Michael Wheeler, who knows the literature and religion of the nineteenth century far better than I do. I thank him, and also Helen Cooper, then Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge, who kindly looked through the pages on Malory.

The text is the product of reading primary sources, medieval and modern; I have read little secondary literature, except in history and art history. I am grateful to the historian Dominic Aidan Bellenger, who improved my history, and to Chloe Johnson, who improved my art history. I owe much to books by Kenneth Clark, Arthur Johnston, Mark Girouard and Christopher Ricks, and to scholars whose names recur in the bibliography. I thank my agent Andrew Hewson, my publisher Robert Baldock and the skilled staff at Yale University Press, especially Rachael Lonsdale. Other debts go back to schooldays, to masters such as Peter Whigham, John Coulson and Hilary Steuert.

Next page