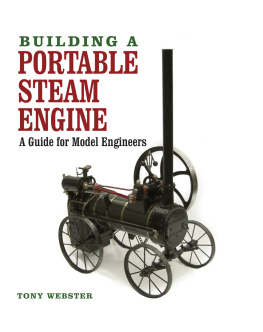

BUILDING A

PORTABLE STEAM ENGINE

A Guide for Model Engineers

TONY WEBSTER

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

Tony Webster 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 866 0

Disclaimer

The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it. If in doubt about any aspect of model engineering, readers are advised to seek professional advice.

Contents

Foreword

Tony Webster is well qualified to write this book on the Lampitt engine. Having known him for many years, I have always been impressed by his ability to root out the unusual prototypes and to adapt simple techniques and materials to do the job. His own collection of models is a testament to his ability and ingenuity. His workshop, housed in the garage of his house, is quite simple and does not contain elaborate machine tools; rather it displays the good solid evidence of hand work and simple fixtures.

If you are a beginner, expect to be instructed in the basic methods rather than sophisticated ones. Although a portable engine is not a complicated affair, there are some tricky techniques to be mastered, but Tony will guide you through them. There is also advice about materials and tools that you should not treat lightly. I have seen not only the model develop from its early stage on the drawing board, but also the original survivor at its home in the East Midlands, not many miles from where we both live. There is nothing ordinary about the prototype; it is a survivor, a representative of a bygone age in which traction engines and portables were built in small numbers by so many little businesses in the agricultural areas of the country. Each has its own unique features, but only the fittest of them survived well into the second quarter of the twentieth century.

I know that some modern techniques are included for the taking. I would urge you to take notice of them, as they will save time and effort and enable you to produce a good result. The boiler is something that must be taken seriously. Making even a simple example demands considerable patience and painstaking work. Above all do not hesitate to get help in this matter. Most experienced model engineers are only too pleased to help a beginner in the hobby.

Now start to enjoy this account of a journey that, I can promise you, will take much longer to complete than you would ever have thought.

D. A. G. Brown, C. Eng.

Introduction

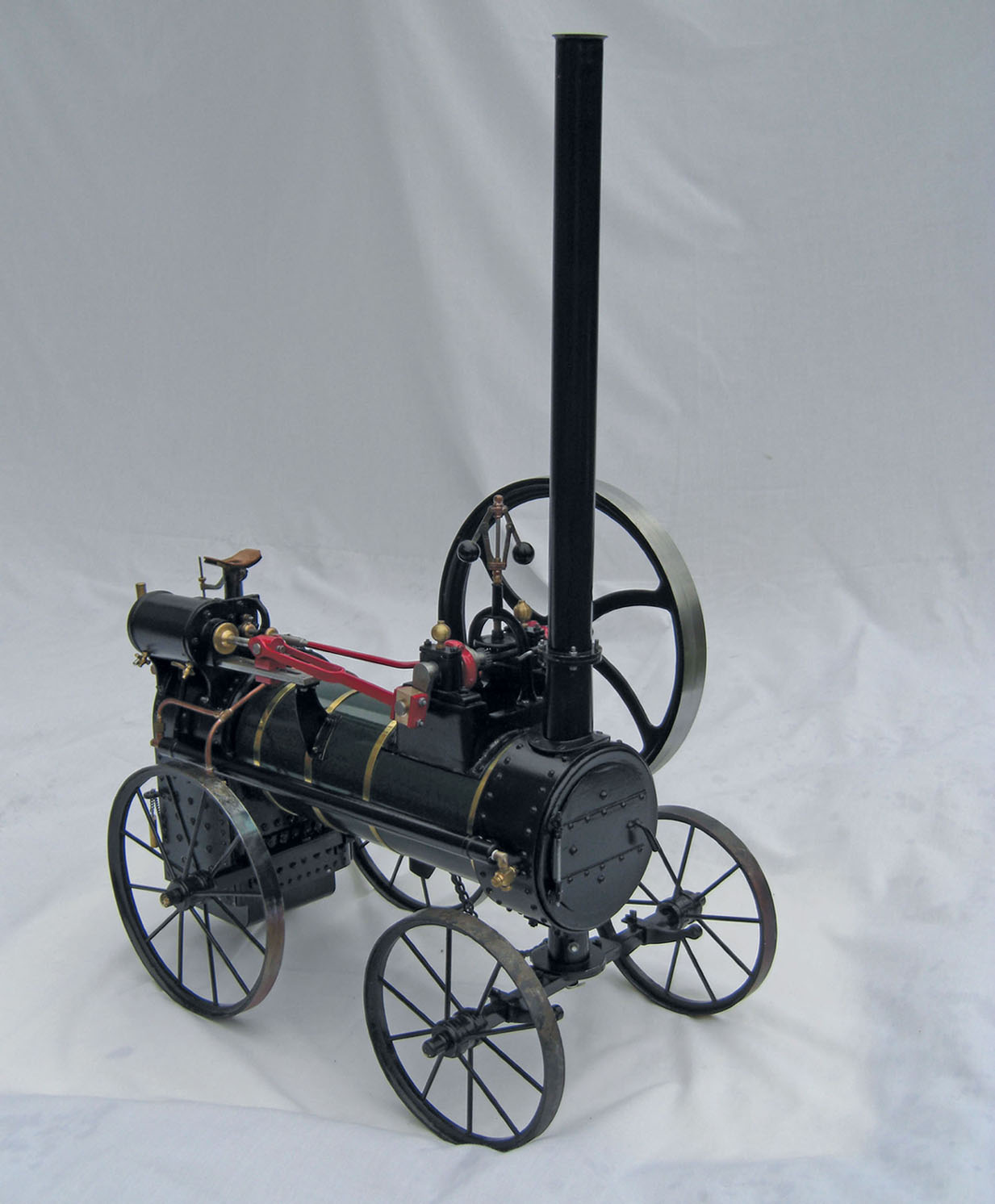

This book details the construction of a portable steam engine and is written for the complete newcomer to model engineering. The making of each part will be described in detail, with hints on sourcing material and buying tools to establish your own workshop. When finished, you will have a complete steam engine that may be used to drive machinery. It will also be worthy of being shown at model-engineering exhibitions where you may receive recognition for the skills you have demonstrated. You will have gained many metalworking skills and completed an engineering apprenticeship of which you can be proud. Along the way you will have met many knowledgeable people and have perhaps joined a new group of like-minded friends.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank my daughter, Susan, for her help with editing and the layout, and Derek Brown for help with the boiler and proof-reading.

This book is dedicated to my wife, Barbara.

1 The Background History and Development of Portable Engines

Portable engines, the forerunner of the traction engine, were made in large numbers in almost every county in the country from the 1830s right through to the 1930s, extending beyond the eclipse of traction engine manufacture. Most of the well-known manufacturers of traction engines produced examples, but many were made by blacksmiths and foundries that are now obscure and forgotten.

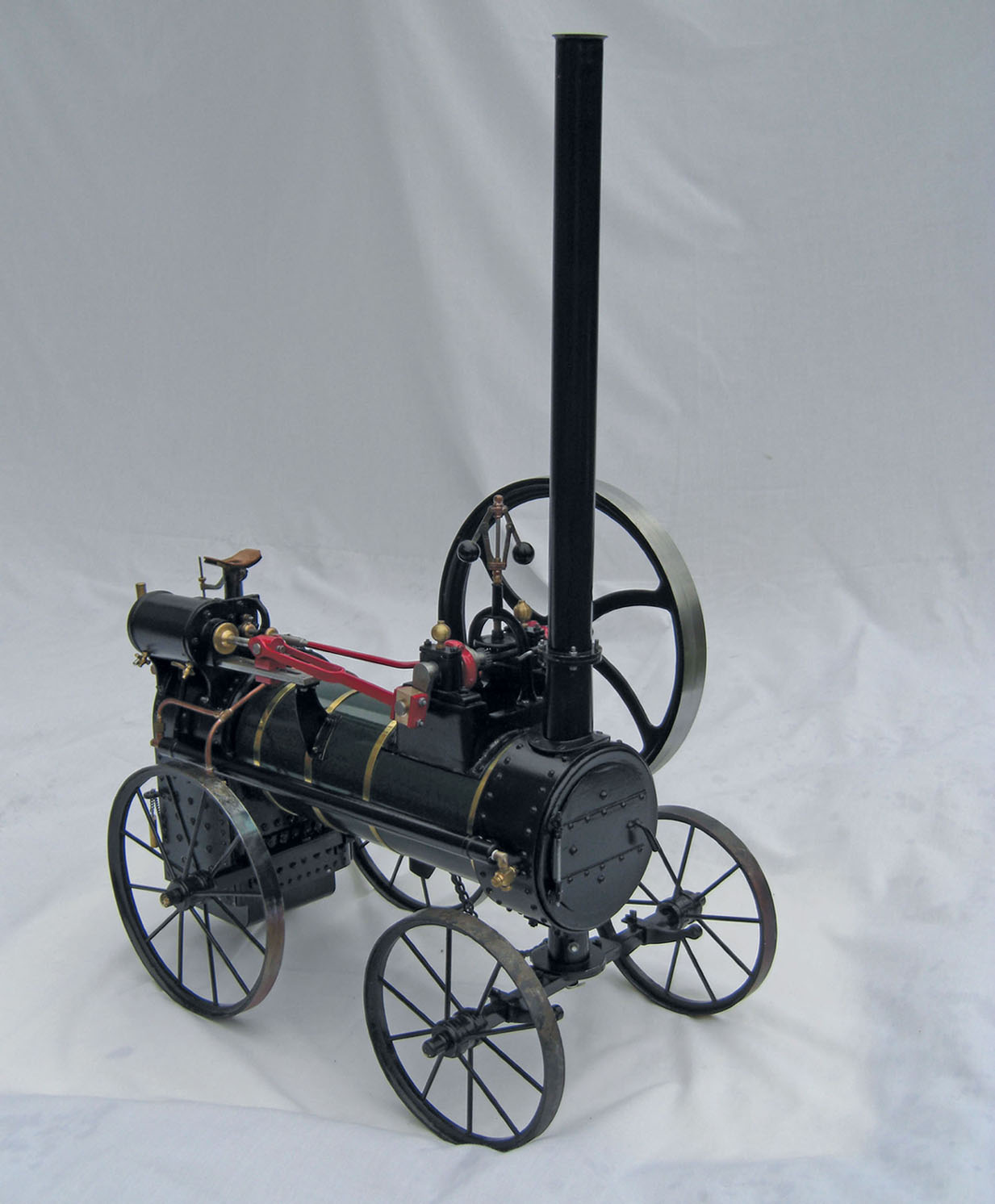

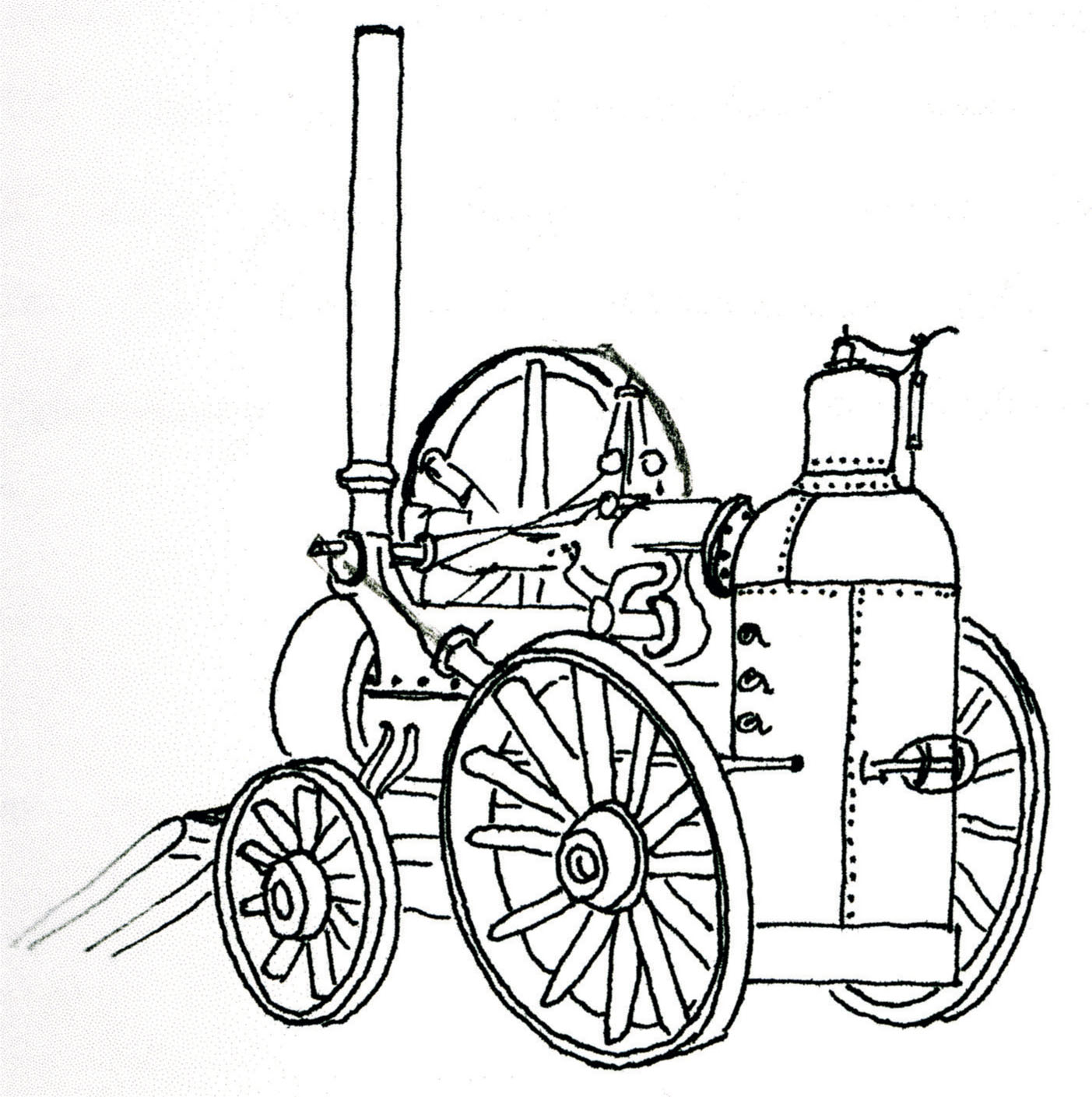

The early portables had horizontal or vertical boilers with a self-contained engine, often mounted on a frame or chassis, and the whole was supported by four wheels. By the 1850s they had developed into using a locomotive type boiler with the engine mounted on the top, indeed using the boiler as part of the structure of the engine. Two large wheels supported the heavy firebox end of the boiler and under the smokebox would be the turntable and two smaller wheels. These would be steered and hauled by a pair of horses in shafts, which would have been necessary to pull the 2 tons of engine over the rough roads of the time. Wrought iron wheels, mounted on a cast iron hub, would have been made in the foundry, or a local wheelwright would have supplied wooden wheels.

A locomotive boiler, as used on railway locomotives, has a large horizontal cylindrical part containing the fire-tubes, with the smokebox and chimney at the front, and a vertical square part containing the firebox at the rear. The steam cylinder was mounted machine, which would have needed another on top of the firebox and the crankshaft over two horses to pull it from farm to farm. Four the cylindrical part at the chimney end. horses might have been needed on wet and

The main use for such engines was to provide rotative power for driving a thrashing machine, which would have needed another two horses to pull it from farm to farm. Four horses might have been needed on wet and muddy winter roads. An outfit comprising a thrashing (or threshing) machine known as a mill in Scotland and an engine was often owned and run by thrashing contractors who travelled from farm to farm all winter, thrashing the farmers corn on the way.

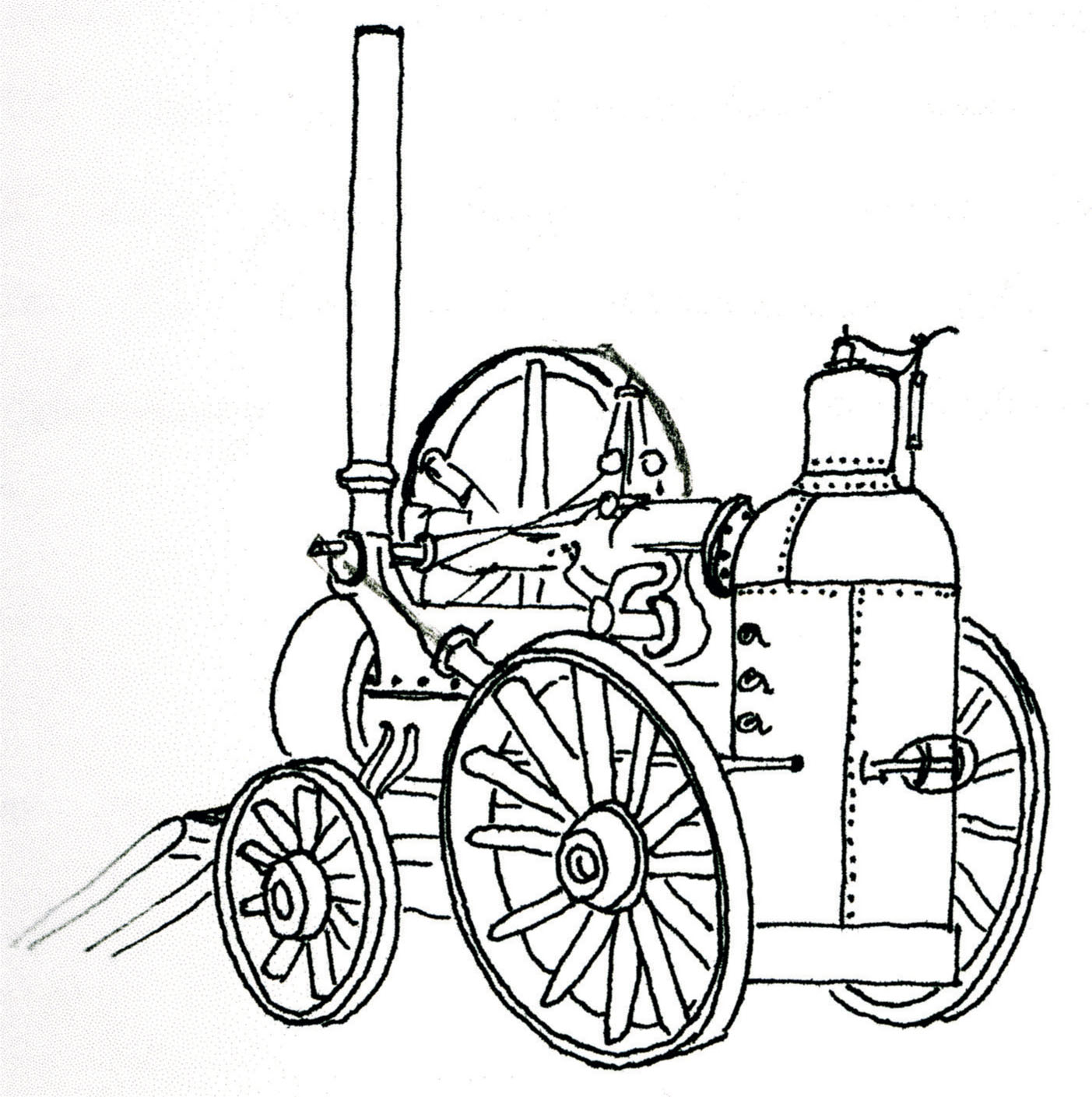

Hornsbys first prize engine of 1848.

A threshing machine, driven by a portable engine, in use in a Northamptonshire village in about 1900. BYFIELD PHOTOGRAPH MUSEUM; COURTESY OF POLLY HARRIS-WATSON

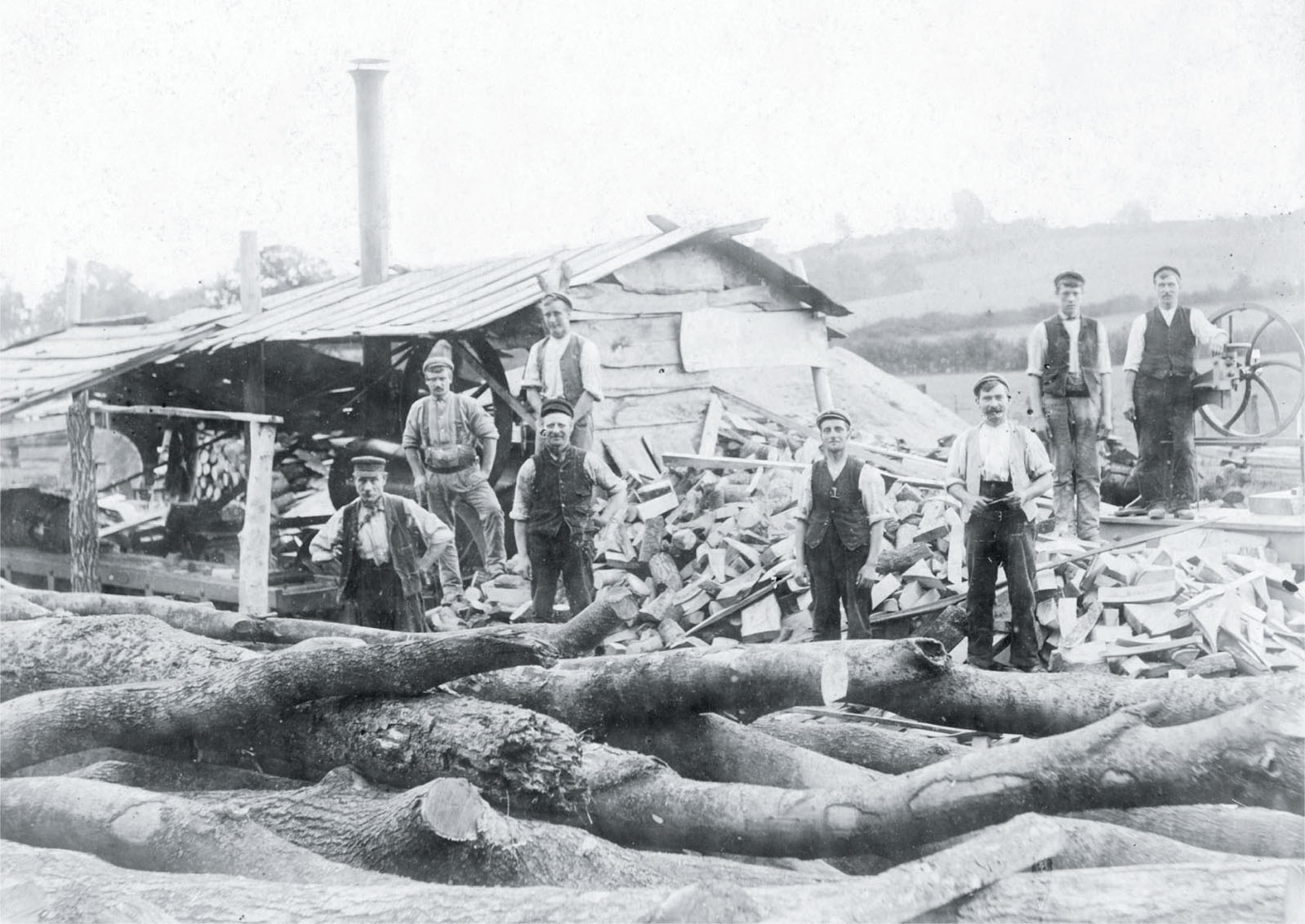

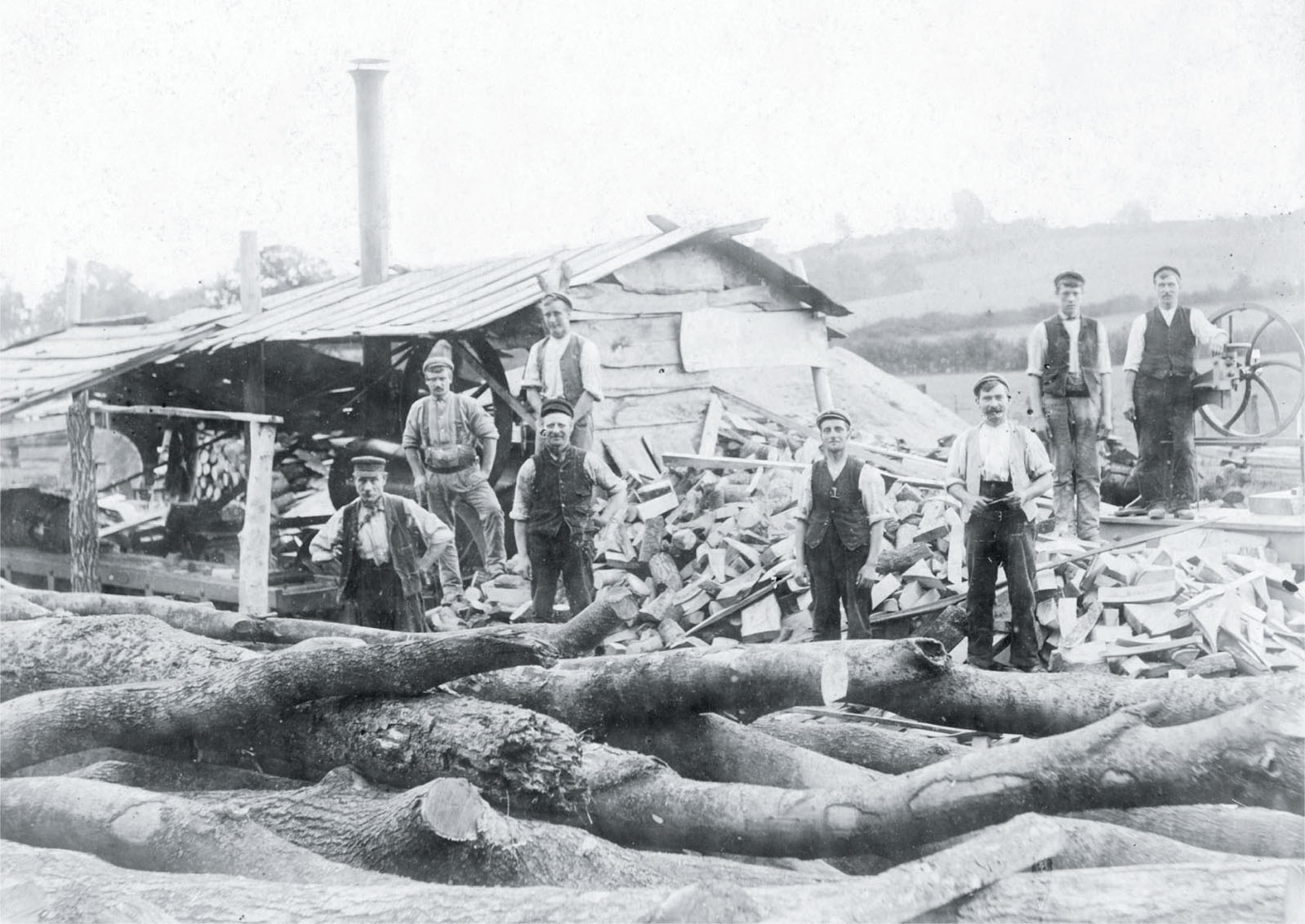

A portable engine driving a circular saw at the village sawmill. BYFIELD PHOTOGRAPH MUSEUM; COURTESY OF KEVIN PERRY

The combine harvester is a modern version of a threshing machine with a cutter-bar on the front and made to be self-moving.

Many sawmills were driven by portable engines that were given a permanent, static home in makeshift sheds made from surplus timber to protect the saw, engine and workers from inclement weather. Sawmill off-cuts provided a readily available supply of fuel for the fire.